Last Updated on: 24th January 2023, 11:56 am

In ancient Egypt, the west side of the Nile River was synonymous with the setting sun, completion and death. That’s why, in addition to the tombs themselves, numerous pharaohs built elaborate temples here to sustain their spirit. While the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut is undoubtedly the main highlight, there are some other gems, like Medinet Habu, that no temple lover should miss.

The following guide includes every single open temple on Luxor’s west bank (as of 2020), along with which ones are essential for those short on time. The temples are presented in chronological order, but this isn’t the order you need to, or even should, visit them in.

Touring the temples of Luxor’s west bank should be combined with visits to the area’s countless tombs. Learn more about logistics and planning out your west bank itinerary at the very end of the article.

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

The most famous temple on our list, situated in an area known as Deir el-Bahari, is also the oldest. But if we’re focusing on chronology, we first have to mention the ruined temple of Mentuhotep II just next to it.

Mentuhotep II (2061-2010 BC) was the 11th Dynasty pharaoh who reunified Egypt after the unstable First Intermediate Period. The 11th Dynasty was the first to be based out of Thebes(Luxor), and Mentuhotep built a large temple here at Deir el-Bahari.

Hatshepsut’s decision to build her own temple here, then, was not a coincidence. Not only did she intend to honor her legendary predecessor, but she was greatly influenced by the Middle Kingdom temple’s architecture.

While now largely in ruins and inaccessible to the public, you can at least get a good view of it from above during your visit.

Who was Hatshepsut?

Hatshepsut (r. 1479-1458 BC) was an 18th Dynasty pharaoh and also one of ancient Egypt’s most controversial figures. She was the daughter of the powerful pharaoh Thutmosis I, known for his successful military campaigns in Asia.

As was fairly common in those times, she married her half brother, Thutmosis II, and became his queen. And it was his son from another wife, Thutmosis III, that was supposed to be next in line for the throne.

But when Thutmosisi II died, Thutmosis III was still a young child. And so Hatshepsut largely handled things until he was deemed old enough to rule. This was hardly unheard of in Egyptian history, and numerous queens had acted as interim rulers in the past.

But Hatshepsut took things a step further by fully declaring herself as pharaoh. She was no longer merely a queen, but Egypt’s first female king.

Controversy surrounding her gender and her ascent to the throne aside, Hatshepsut proved to be a formidable ruler. She sent an expedition to Punt (more below) and instigated numerous building campaigns throughout the country.

She also sent forth a number of military campaigns into Asia and Nubia, most of which were led by her stepson and co-regent, Thutmosis III.

Even after coming of age, Thutmosis III remained in his stepmother’s shadow until she finally passed away. Though he later destroyed most of her monuments and had her erased from the history books, he never touched her mortuary temple.

The motives behind Thutmosis III’s actions remain a mystery. But he likely destroyed Hatshepsut’s monuments in order to secure his own legacy. After all, Hatshepsut was never supposed to be pharaoh.

We should be grateful that Thutmosis left this temple alone, as the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut is easily one of Egypt’s finest. And it would even go on to have a major influence on modern architecture.

Who was Senmut?

The temple was designed by Hatshepsut’s chief official and architect, Senmut (also known as Senenmut). It’s unique in Egypt for having been integrated with its natural setting.

Senmut’s story is a remarkable one. He was born as a lower class commoner, but gradually rose the ranks to become one of Egypt’s highest-ranking officials.

Senmut was responsible for quarrying and erecting Hatshepsut’s obelisks at Karnak. And he was also entrusted to be the tutor and caregiver of Hatshepsut’s daughter, Neferure.

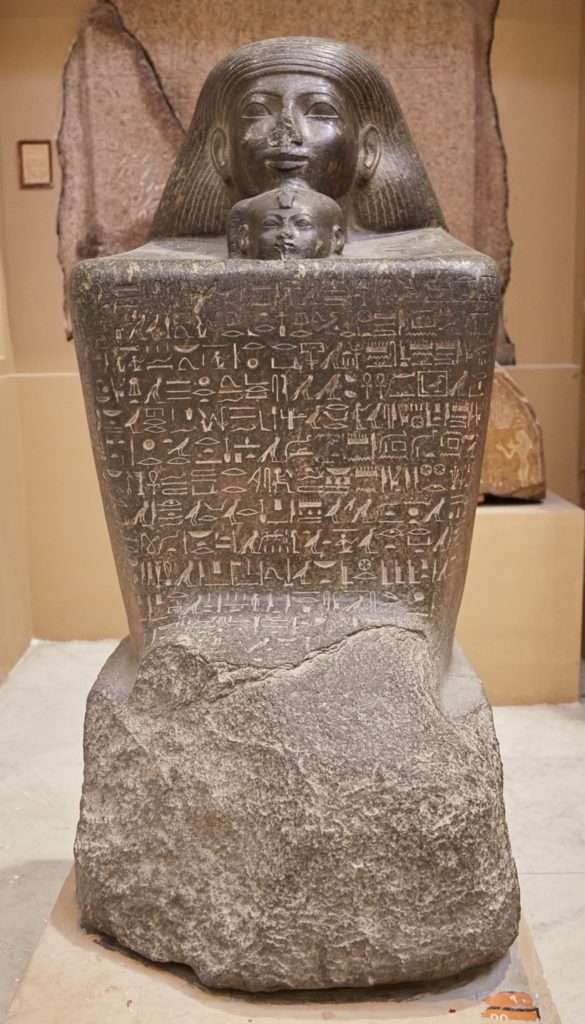

During your visit to the Cairo Museum, don’t miss the charming block statues of Senmut and his young pupil. While the Egyptians didn’t create much art that we’d call ‘adorable’ today, these sculptures are notable exceptions!

Many speculate that Senmut and Hatshepsut were lovers, though we have no evidence to confirm this. But in a cavern nearby the temple, there’s some eyebrow-raising graffiti which depicts a man having sex with a woman wearing the pharaonic headdress.

This was likely drawn by a laborer who hung out in the cavern to escape the sun. And many presume that the couple in question are Senmut and Hatshepsut. Perhaps some believed that Senmut was the one really calling the shots? (I tried to go and see the sketch for myself, but the whole side area was off-limits during my visit.)

Strangely, all records of Senmut cease from around 5 years before the end of Hatshepsut’s reign. All sorts of theories have emerged surrounding Senmut’s death or possible disappearance. But in truth, all we know is that mentions of his name stop. That’s it. And we also don’t know how Hatshepsut eventually died, only that Thutmosis III took over as the sole ruler afterward.

Hatshepsut was omitted from kings lists throughout the remainder of Egyptian history. Nevertheless, even the Ptolemaic-era priest Manetho knew of her. And she was especially a major inspiration for Arsinoe II (316-270 BC), wife of Ptolemy II.

The Temple

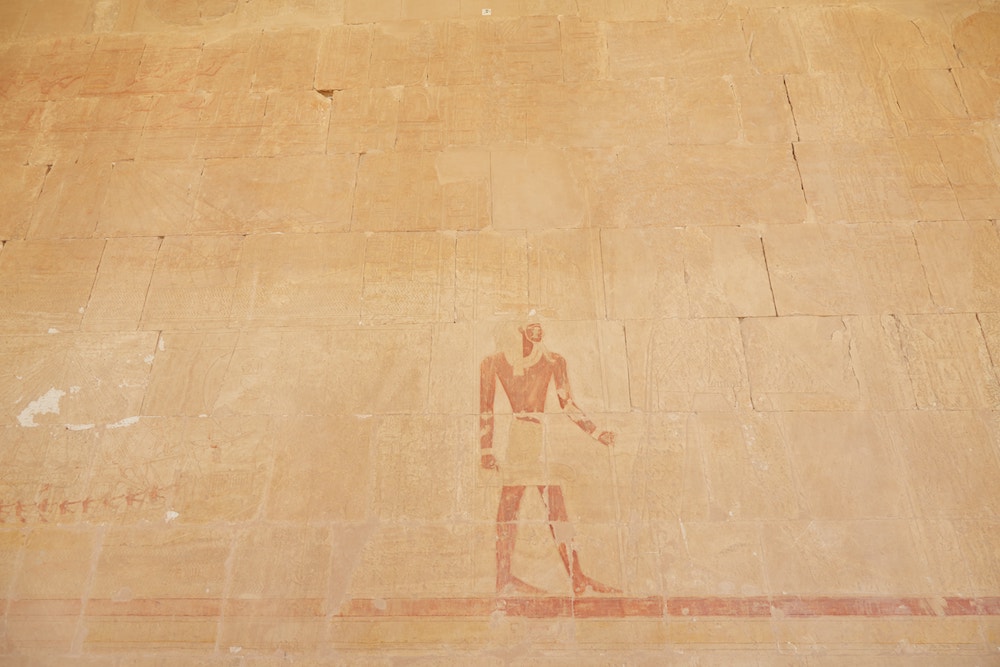

A long causeway leads to the temple, which would’ve originally been lined by sphinxes. It also once had pools and gardens on either side, which included plants brought from Punt.

The temple itself, meanwhile, is divided into three levels, and most visitors start at the second. Over to the far left is the Hathor chapel, dedicated to ancient Egypt’s great Mother Goddess.

The chapel contains interesting sixteen-sided columns which appear to be round at first glance. The other ones are square, and they’re all topped with Hathor capitals.

As Hathor was typically depicted as a cow, the reliefs show Hatshepsut drinking milk from Hathor’s udder. On the rear wall, meanwhile, Hatshepsut’s late husband Thutmosis II is shown having his hand licked by a cow.

Much of the original color remains in the accompanying chapel. The alcove to the right contains an image of Senmut, which scholars suspect may have been put there against Hatshepsut’s wishes. It’s also this Hathor chapel that provides the best views of Mentuhotep II’s temple mentioned above.

Continuing to the right, visitors enter the long pillared hall entirely dedicated to reliefs of Hatshepsut’s Punt expedition.

Throughout Egyptian history, pharaohs would send trading expeditions to the Land of Punt. The region was known for being rich in things like resins, myrrh, ivory and other valuable resources.

But the journey was a long and treacherous one. And the Egyptians likely had to drag their boats across the desert to get to the Red Sea. Therefore, rulers who managed to pull it off earned major bragging rights. (The earliest Punt expedition we know of was carried out by Sahure of the 5th Dynasty.)

To this day, the exact location of Punt remains a mystery, though it’s commonly believed to be Somalia or a neighboring country. As seen by the reliefs here, it was definitely somewhere in sub-Saharan Africa.

The scenes begin on the far left, showing Punt citizens living in huts. Notice the Queen of Punt on the left wall. Her extraordinarily curvy figure is highly unlike how any Egyptian woman was ever depicted.

Interestingly, the Punt drawings show many detailed images of plants, though there’s no known location where all such plants grow in the same place.

And notably, battle scenes are completely missing from this temple. Was this perhaps to conform with Hatshepsut’s femininity?

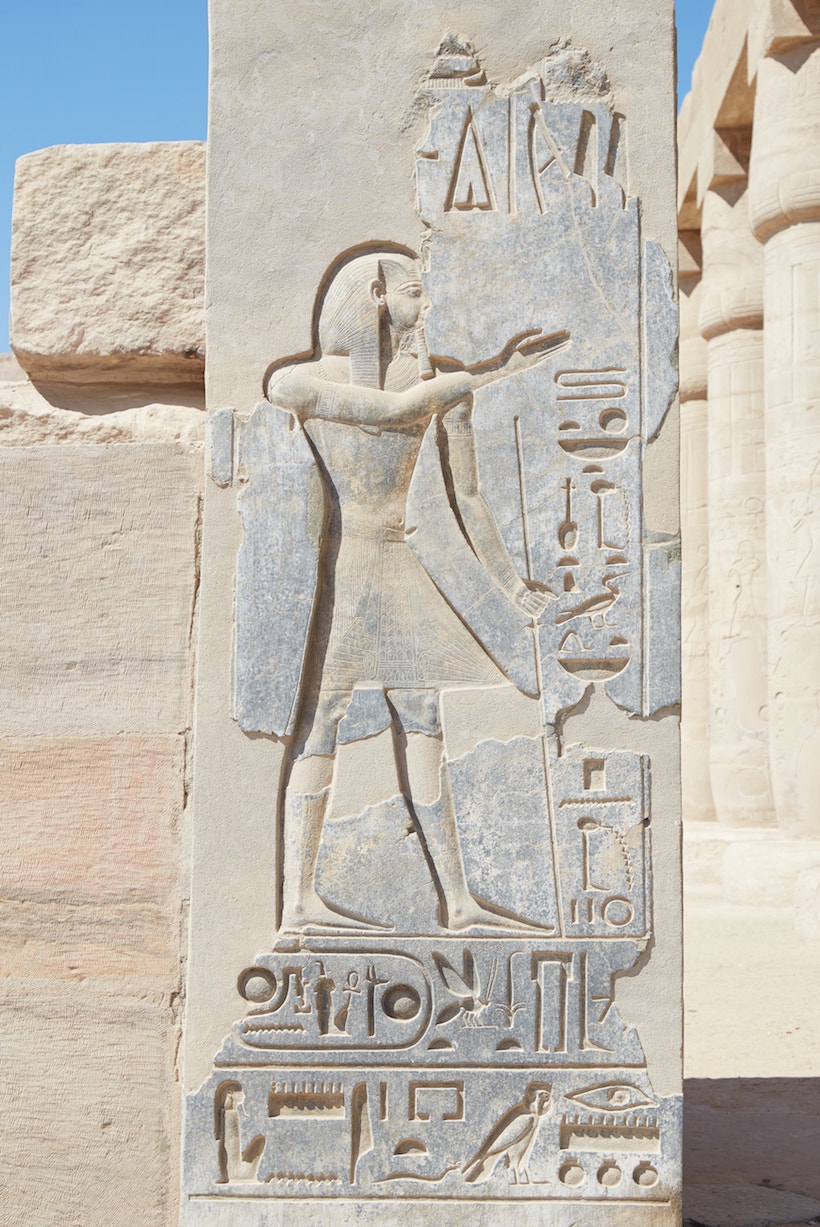

The reliefs continue over on the right side of the ramp. Here the subject matter changes to Hatshepsut’s ‘divine conception.’ Throughout her reign, she repeatedly claimed to be a child of Amun.

Scholars call these scenes political propaganda. But the idea of the Egyptian pharaoh being conceived by the gods dates back to the beginning of their civilization. The scenes here likely inspired the reliefs in Luxor Temple’s ‘Hall of Theogamy,’ which depict the divine conception of Amenhotep III.

Though mostly intact, much of the reliefs’ original color has been lost. And the carvings are very, very fine.

Also note that while arriving in the early morning is a must if you want to see the temple facade without the crowds, it’s also the worst time to see the reliefs.

The sun shines in through the gaps in the pillars, making for very uneven lighting conditions. The afternoon is the best time to see the reliefs. But given how faint they are, they’re not that easy to make out at any time of day.

To the far right of the second level is the Anubis Chapel. Thankfully, the colors are in much better condition here and it’s easier to appreciate the beautiful artwork. You’ll see gods like Ra, Horus, Osiris and of course, Anubis, to whom the chapel is dedicated.

Anubis is the jackal-headed god of mummification who assists Osiris in the underworld. While he was around since the beginning of Egyptian civilization, he only started to play a major role in tomb and temple reliefs from the New Kingdom onward.

On the third level of the temple, you can see numerous statues of Hatshepsut as Osiris. This is a common motif you’ll find at temples all throughout Egypt. But it’s interesting here to see this female pharaoh identifying herself with a male deity.

The upper court is home to a temple for Amun. Later on, the Ptolemies enlarged it and built a temple in dedication to their two favorite non-royal Egyptians: Imhotep and Amenhotep, son of Hapu.

Over to the far right is an additional Anubis shrine, though it was off-limits during my visit. Supposedly, it contains images of Thutmosis I, while the images of Hatshepsut were later erased. Outside, meanwhile, is an impressive open-air sacrificial altar.

Elsewhere in Deir al Bahari are numerous rock-cut tombs, though they’re currently off-limits to visitors. It was in one of them that dozens of royal mummies were found in 1881. They were likely moved to the spot after their tombs were pillaged during the 20th and 21st Dynasties.

The first level of the temple is also accessible, though almost no tourists seem to go there. The reliefs show the obelisks of Karnak being transported over water from Aswan. Interestingly, the outer columns here are square while the interior ones are round.

The Mortuary Temple of Thutmosis III

After Hatshepsut’s death, Thutmosis III finally got to take the throne that was rightly his. And while he may not be as fondly remembered today as his stepmother, he turned out to be one of Egyptian history’s most dominant pharaohs.

Often dubbed the ‘Napoleon and Egypt,’ Thutmosis III conquered vast swathes of territory, converting Egypt from a kingdom to an empire.

Be that as it may, there’s hardly anything left of his mortuary temple. All you can see are dilapidated mudbrick foundations and some pots buried in a pit – hardly befitting of such a powerful monarch.

But if you have a bicycle and a Luxor Pass, the temple is on the main road connecting many of the other major temples. You might as well stop by for a couple of minutes. Just beware of the pushy guard asking for money.

If you really want to pay your respects to Thutmosis III, his Festival Temple at the eastern end of Karnak is remarkably well preserved.

Colossi of Memnon

Skipping ahead in time about 100 years, but still within the 18th Dynasty, is one of Luxor’s most famous landmarks. But not many people realize that the Colossi of Memnon were not standalone structures. They were once merely just a part of Amenhotep III’s massive mortuary temple.

The breathtaking statues, which stand at 18 m high, were carved from quartzite sandstone brought from the Edfu area. They were designed by Amenhotep, son of Hapu, the mastermind behind Luxor Temple.

According to legend, Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple was once the largest temple in all of Egypt! Sadly, the temple was gradually destroyed by the flooding of the Nile, and only the colossi and some foundations remain.

Most tourists just stop to look at the colossi for several moments before moving on. And at the time of writing, that’s all anyone can do. But with excavations currently taking place, expect for the full temple – or at least what’s left of it – to open up as a tourist attraction in the future.

But who’s Memnon? The name was given by the Romans, who wrongly attributed the statues to the legendary Ethiopian king Memnon, who fought against the Greeks in the Trojan War.

The statues were also believed to be some sort of oracle, and Emperor Hadrian even visited and set up camp near the statues for awhile.

Strangest of all, though, is that the statues used to ‘sing’ every morning around sunrise. Numerous ancient historians and travelers have commented on hearing this, meaning it’s more than just a legend.

While we don’t know for sure, it’s possible that the sudden rise in temperature and the evaporation of morning dew caused the sandstone to hum.

In any case, the statues collapsed during an earthquake in 27 AD. And while they were put back together, the Colossi of Memnon have never sung another tune since.

Further back, you can see two smaller (but still huge!) statues in the middle of the former temple.

And on the opposite side, just near the Mortuary Temple of Merenptah, are two standing colossi that were once part of the original temple. They were erected in 2015 as part of a joint mission between Egypt and various European countries.

But for fans of Amenhotep III, that’s not all. You can also go and visit the ruins of his expansive royal palace, known as Malkata. It’s well out of the way, and only for the adventurous traveler who’s already seen it all in Luxor.

About a ten-minute bike ride from Medinet Habu, you can pass it on the way to the Roman Isis Temple.

The Mortuary Temple of Seti I

Immediately following the glory years of Amenhotep III’s reign, Egypt was taken on a wild ride by the ‘heretic king’ Akhenaten. He changed Egypt’s religion, its artwork and he even tried to erase mentions of Amun from Luxor’s temples.

The next few kings of the 18th Dynasty would then try to undo Akhenaten’s changes, but none of them made a tremendous impact.

It wasn’t until the reign of Seti I, the second king of the 19th Dynasty (following his father’s one-year reign) that major monuments were built again in the traditional style. And one way in which Seti I hoped to restore order was by creating some of the most beautiful artwork that Egypt had ever seen.

There are several places you can experience the remarkable reliefs of Seti I. They’re Abydos, the Hypostyle Hall of Karnak, Seti I’s tomb in the nearby Valley of the Kings, and here at his mortuary temple.

As only a third of the original structure still stands, this temple is the least impressive of the bunch. But it’s still worth visiting for fans of this underrated pharaoh.

The color is missing from most of the reliefs, but you can still clearly make out the beautiful carvings in the right lighting. The temple was later finished by Seti I’s famous son, Ramesses II. And you don’t have to be an art expert to notice the obvious differences between the two styles.

While Ramesses II created Egypt’s most astonishing colossal statues, his reliefs we generally subpar. Did Seti I’s head artist pass away, or was Ramesses II simply more concerned with quantity over quality when it came to temple reliefs? While we may never know, the stark contrast can also be experienced at the temple of Abydos.

Not many visitors come here, despite it being fairly close to the Valley of the Kings. I was the only person at the temple during my visit, and the guard didn’t hesitate to take me up to the roof! Of course, he expected a tip, but it made for a fun little adventure.

The Ramesseum

Ramesses II, the son of Set I, reigned for 66 years and initiated more building projects than any other pharaoh. He made additions to temples like Karnak, Luxor Temple and his father’s Osiris temple at Abydos. He also built the astounding rock-cut temple of Abu Simbel, south of Aswan. But how does his own mortuary temple compare?

Known as the Ramesseum, Ramesses II’s mortuary temple is not in the best of shape today. But there are a few notable features that make it worth visiting.

Started in the second year of his reign and under construction for 20 years, it was robbed and looted during later dynasties. This is ironic considering how Ramesses II supposedly stripped many Old and Middle Kingdom monuments of their stone.

One of the highlights of the Ramesseum is the collapsed and shattered colossus. Ramesses II created the finest and largest colossal statues ever made. And he did so out of granite, one of the hardest stones.

Today you can see them at places like Luxor Temple or Memphis. But this one would’ve once been the largest of them all.

Originally weighing over 1,000 tons, it was carved from a single block of granite shipped from Aswan. It originally stood at around 18 m high until it was brought down by an earthquake. This statue was even the inspiration for the famous poem Ozymandias.

Moving on, the pylon of the temple is decorated with scenes of the Battle of Kadesh. According to legend, Ramesses II was on a military expedition in Syria when he was betrayed and found himself alone on the battlefield. Amun then inhabited his body, allowing him to kill scores of enemy Hittite troops.

In addition to a series of Osiris statues, you can also find the remnants of the Hypostyle Hall. The ceiling has well-preserved reliefs containing detailed astronomical and astrological information.

Notice the circle in the boat. Could this be a depiction of an exploding supernova?

On the rear wall, there’s a large relief of the king seated in the presence of Thoth, who inscribes his name and regnal years in a tree. The scene is meant to symbolize the eternalization of the pharaoh’s reign. And the tree may be a Persea, a type of avocado tree native to Egypt.

During your visit, you can also walk around and explore the various mudbrick structures around the area. Clearly, the Ramesseum was much more elaborate and expansive than it appears today.

While this list is mostly chronological, here’s one exception. Just next to the Ramesseum is the ruined mortuary temple of Amenhotep II, the son of Thutmosis III and the grandfather of Amenhotep III. There’s really not much to see other than an interesting Anubis statue.

The Ramesseum is situated just across the road from the Tombs of the Nobles, so combining a visit makes sense (learn more below).

The Funerary Temple of Merenptah

Merenptah (also known as Merneptah) was Ramesses II’s son. Other than some mudbrick foundations and propped up stones that were found around the area, there’s not much left at all of this temple.

Be that as it may, this scant temple is open for tourists and even has its own guard.

The site is on the main road connecting many of the other temples on this list, making it easy to reach. But this has to be one of the loneliest sites in Luxor, and is only worth a stop for those who really want to see it all.

Medinet Habu

Medinet Habu is the name for the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III (r. 1186-1155 BC). It’s easily the west bank’s most impressive temple after Hatshepsut’s. But for some reason, hardly any tourists visit it, making it one of Luxor’s top hidden gems.

Ramesses III was a pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty who’s widely considered to be Egypt’s last great king. He fended off attacks from Libya and also from a coalition of ‘Sea People’ from the north. As such, he made a name for himself as a great warrior king.

And Medinet Habu was his most major construction project. Though his reign took place around 100 years after that of Ramesses II, Medinet Habu was largely modeled after the Ramesseum.

Thankfully, it’s in a much better state of preservation. But that’s partly because Medinet Habu uses a bunch of the Ramesseum’s stone!

The entrance to the temple is through a portal in the style of a Syrian fortress, which Napolean’s men named the ‘Pavilion.’ Supposedly, it was once part of a royal palace that was connected to the temple.

Reliefs on the walls show scenes of the king in his harem (which was likely on the 2nd floor) and the king at war. On the north wall of the court, notice the unique relief of the king making offerings to Set. (Set’s face is sadly missing.)

In Egyptian mythology, Set was the adversary of both Osiris and Horus. He represents chaos and the disruption of the natural order, or Maat.

Be that as it may, Set plays a necessary role in the universe, and he can never be eliminated entirely. In order to overcome opposition, there needs to be some kind of oppositional force in the first place!

Before the first temple gate, there are two interesting structures on either side of the walkway. To the right is a temple that was started by Amenhotep I and then completed by Hatshepsut. The queen’s name was later removed by Thutmosis III, and references to Amun were then scratched out by Akhenaten.

This site is highly important to Egyptian mythology, as it’s believed to be the location of the Primeval Hill. It’s at this very spot where matter first emerged from chaos, and where the Eight Primordials were buried! Unfortunately, the temple was closed off during my visit.

Over to the left is the Shrine of Amenerdais, a princess of one of the Ethiopian kings of the Late Period. This structure was also off-limits.

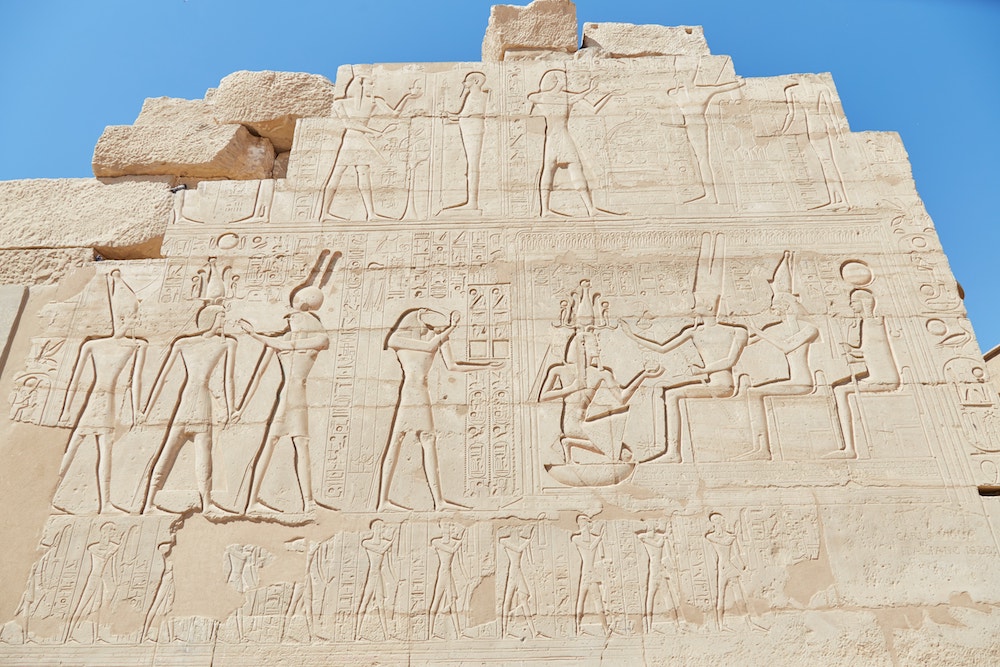

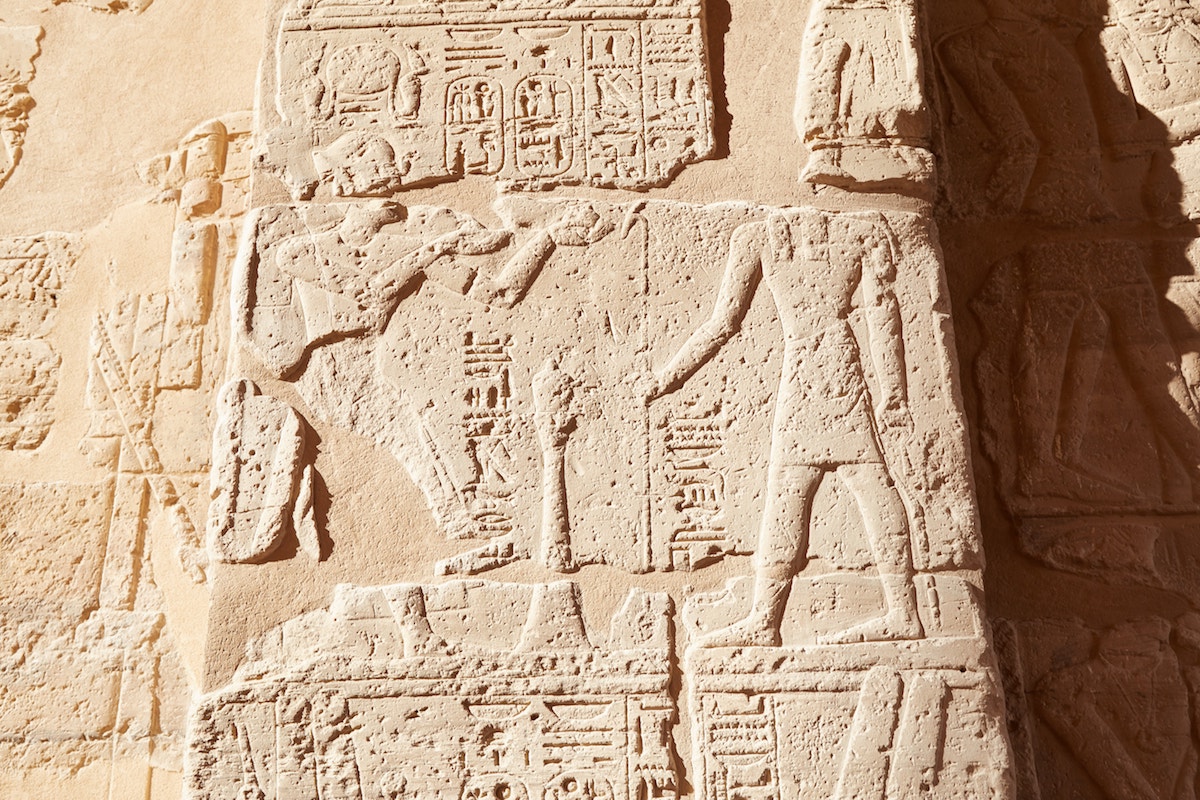

After walking through a well-preserved pylon carved with battle scenes, visitors arrive in the first court. The court is flanked on either side by colonnades.

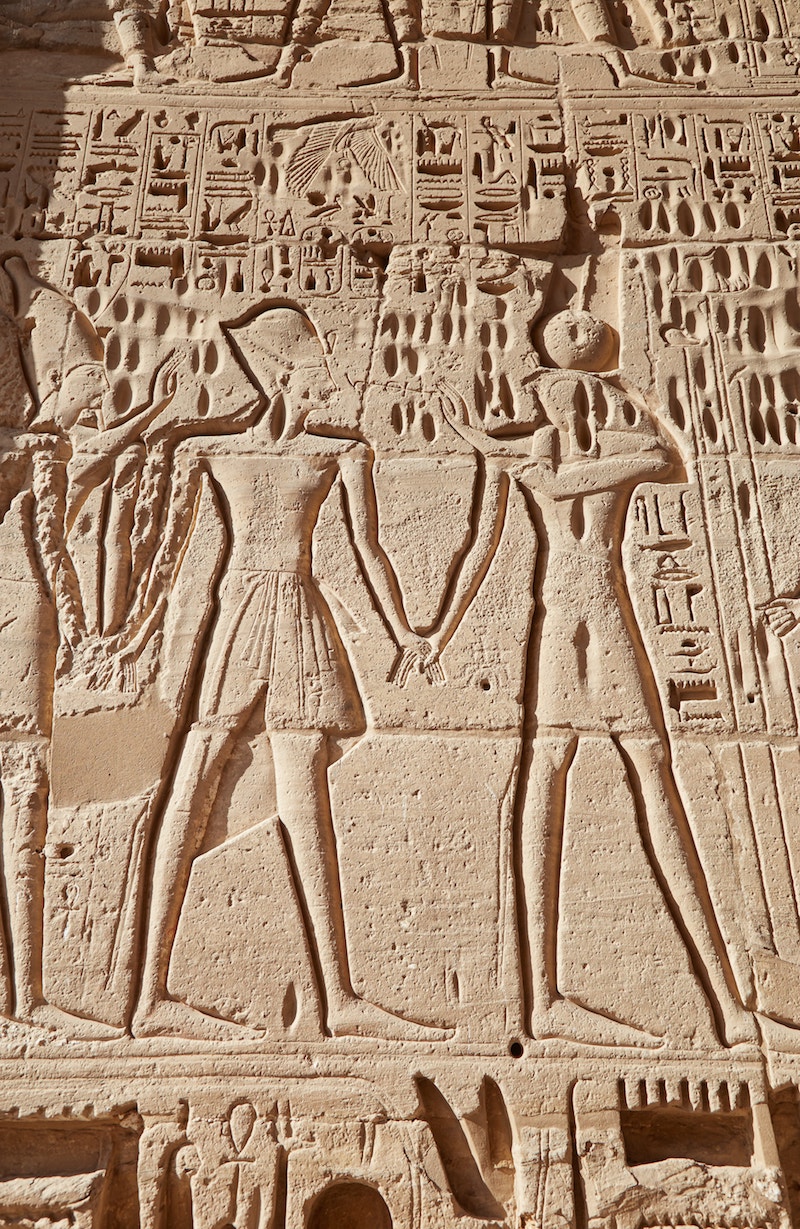

The northern columns portray the king as Osiris. Interestingly, while the statues appear to be separate, they’re actually connected to the columns.

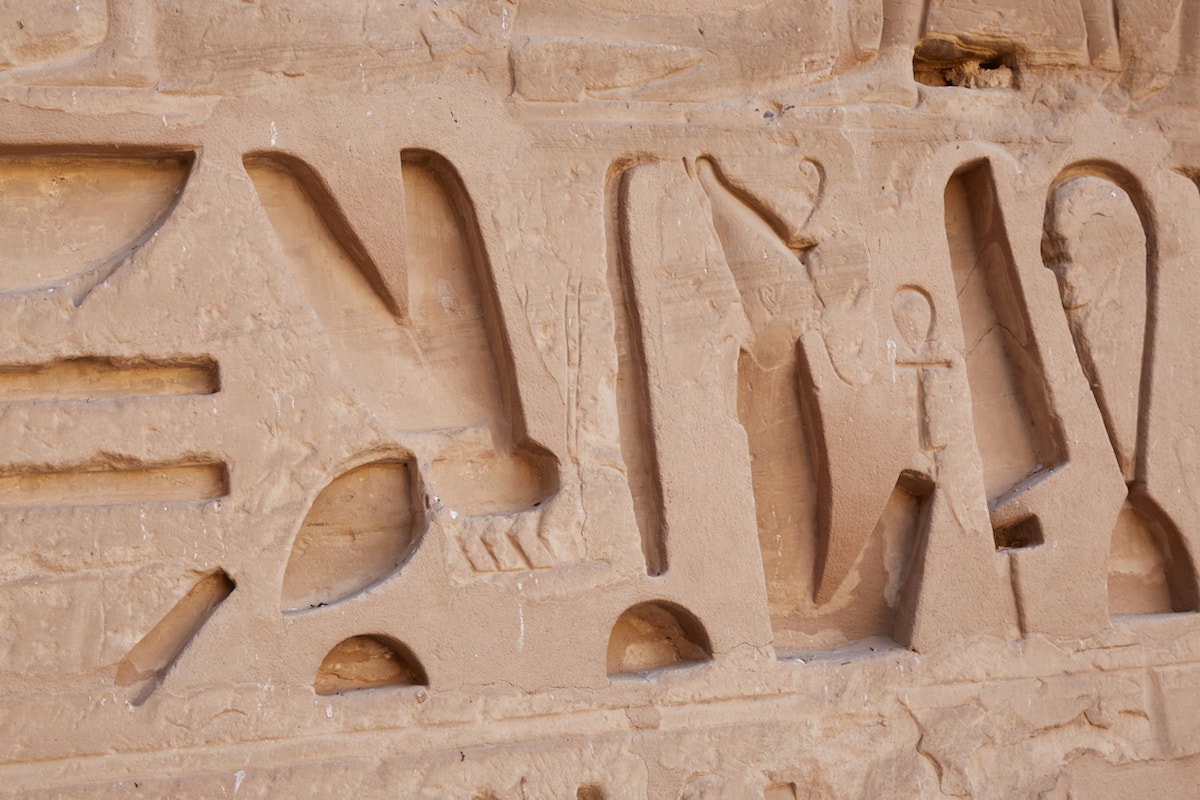

One of the main distinctions of Ramesses III’s constructions is their incredibly deep carvings. They were seemingly hammered brutally, with some as deep as 8 inches. This must’ve been the ancient Egyptian equivalent of typing in all caps.

But why? Scholars believe that Ramesses III wanted to prevent usurpation by future kings. And this seems like the only reasonable explanation, though it’s still just conjecture.

In the 19th Dynasty, Ramesses II was notorious for taking over the statues and monuments of his predecessors, changing the inscribed names to his own. But strangely, the names were not changed again by later kings. This suggests that there may have been a hidden meaning or deeper significance to these ‘usurpations.’

Another remarkable aspect of Medinet Habu is how much of the original color remains. Though many people tend to picture Egyptian temples as we see them today – sand-colored monochrome structures – they were originally bursting with color.

Moving through the second pylon, you’ll arrive at the second court. And next is the Hypostyle Hall, which was originally roofed over. You’ll then find a series of sanctuaries and treasuries which are fun to explore – especially if you’re the only visitor.

Before leaving Medinet Habu, it’s also worth checking out the exterior walls of the temple, which are all covered in battle scenes. The east wall shows Syrians, the southern wall Nubians, the western wall Libyans, and the northern wall the ‘Sea People.’

Together, these four groups represented the four directions, or the four corners of the world with Egypt at the center.

The Temple of Deir el-Medina

All of the temples listed above were mortuary temples, but the next two are exceptions. And they were also built around a millennium after Medinet Habu.

This Ptolemaic-era temple is situated just near the workers’ tombs of Deir el-Medina. Founded during the reign of Ptolemy IV, the temple was dedicated to the goddesses Hathor and Maat.

What’s more is that it was also dedicated to the Ptolemies’ two favorite ancient mortals: Imhotep and Amenhotep, son of Hapu (architect of Amenhotep III). Supposedly, a much older temple once existed here that was designed by Amenhotep, son of Hapu himself.

The temple is small but full of well-preserved reliefs. In the back, in the left-hand shrine, is a beautiful rendition of the ‘Weighing of the Heart‘ scene. This is a rare example of this traditional scene being depicted in a temple instead of a tomb.

Also above the doorway is a four-headed ram representing the four directions. It could possibly be the metaphorical ‘god with four faces’ mentioned as early as the Pyramid Texts.

Just out back, meanwhile, are the ruins of a former Coptic Church. It’s rather peculiar how the early Christians denounced ‘paganism’ while also building churches within these ‘demonic’ temple precincts.

The Roman Isis Temple

The last item on this list is the most obscure and the most difficult temple to get to in Luxor. On top of that, it’s also probably the smallest. The temple was built around the 1st century AD and is officially known as Deir el-Shelwit.

While Osiris was one of the most popular Egyptian gods of the Ptolemaic era, his wife Isis was devoutly worshipped by the Romans. In fact, Isis was worshipped in various parts of the Roman Empire – not just in Egypt.

Various Roman emperors added to the temple for around 100 years. One of the most interesting things about visiting Roman-era temples is seeing how the emperors were represented as typical Egyptian pharaohs.

During the Roman occupation, Roman emperors even had their own cartouches (official pharaonic name inscribed within an oval). Throughout the temple are the cartouches of Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Julius Caesar and others.

And over by the original gateway, you can see depictions of Roman emperors like Galba, Otho and Vespasian – three of the four monarchs who ruled Rome in the year 69 AD alone. Otho is shown spearing a turtle, who is a representation of Set.

To be frank, the temple is only worth it if you’ve seen everything else and find yourself with a free day. There are much more impressive Roman-era temples to check out on the way to Aswan. But if you still want to visit, here’s how:

GETTING THERE: The Roman Isis Temple is about 15-20 minutes southwest by bicycle from Medinet Habu. On the way there, you can stop at Malkata, the former palace of Amenhotep III.

Following Google Maps is pretty straightforward. While the roads are mostly unpaved in this area, it’s not too difficult to traverse by bicycle. You can also hire one of the guys at the cafe across from Medinet Habu to take you as well.

Additional Info

To fully explore Luxor’s west bank, including its tombs and mortuary temples, set aside three full days. But you can still see the main highlights if you only have two.

While I planned for three, I ended up having an extra fourth day in the area, which I used to revisit some of my favorite tombs and to check out the Roman Isis Temple.

I stayed on the west bank and got around each day by bicycle. Also, I had the Luxor Pass which gave me unlimited access to every site in town. This also made exploration much easier and hassle-free.

With so much to see in Luxor, there are lots of different itineraries you could arrange, but I’ll go over what I did. The routes should also be applicable for those hiring a driver for the day.

DAY 1: Bike (or drive) down the main road from the ferry port area toward the desert. Stop at the Colossi of Memnon.

Head west to visit Medinet Habu. If you get there early enough, you should be the only visitor there. Conveniently, there are some cafes out front if you missed breakfast.

Next, head further north to the Valley of the Queens. There are only four tombs to see here, including the extra special (and expensive) tomb of Nefertari.

Then head a bit east down the road to the workers’ tombs of Deir el-Medina. See the few tombs that are open in addition to the Ptolemaic temple.

Next, ride back to the main road connecting most of the main temples. Head toward the Ramesseum (though you can stop at Merenptah’s temple along the way if you wish).

After the Ramesseum, just across the road are the ‘Tombs of the Nobles.’ Only around five tombs are open here at any given time. (There are many other tombs scattered throughout the west bank that belonged to nobles, though each little cluster aside from this one has its own special name.)

This would be a good place to call it a day. But if you only have 2 full days in Luxor, then see whatever you can nearby before things close around 4PM.

Departing at around 7:00, expect to finish at roughly 14:30.

DAY 2: If you’re getting around by bicycle, this is going to be a tiring day. But it’s definitely possible if you’re reasonably fit. If you’re not feeling too energetic, you may want to hire a driver.

Wake up early and get to the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut as early as possible. The site opens from 6:00. (I only managed to get there as early as 7:45, and there were already groups of people there. It starts to get real crowded from around 8:30. If you don’t care about photographing the temple without other tourists in the way, the afternoon is a better time to see the reliefs.)

If you’re really into tombs, you can stop at the nobles’ tombs of Asasif on the way back to the main road. There are three tombs here with some nice artwork, but they’re not essential.

Next, head to the Valley of the Kings. You’ll first have to return to the main road and then head further north before making a left. Thankfully, the signage is pretty adequate around here.

It’s a long uphill bike ride to the valley, though the ride back down is a lot of fun. If you have the Luxor Pass, you can see every tomb (around 12), but normal tickets only allow visitors to see three. If you don’t have the Luxor Pass, visit three regular tombs and also buy the extra ticket for Ramesses VI’s tomb, which is the best after Seti I’s.

On the way back, you can stop by the nobles’ tombs of Roy and Shuroy. These are some of the best nobles’ tombs in Luxor.

DAY 3: Start with Seti I’s temple if you haven’t seen it yet. This is the northeasternmost temple on the west bank. You can then head back along the main road, stopping at various places on the way.

At the intersection nearby the Seti I temple is the Carter House which includes a full replica of King Tut’s tomb.

If you like, you can revisit the Valley of the Kings. Or keep heading down the main road, checking out various minor mortuary temples (like that of Thutmosis III) or nobles’ tombs (such as Kokha and Drabu el-Naga – see our guide for a complete list).

DAY 4: If you find yourself with yet another day to explore the west bank, this might be a good time to have a leisurely bike ride over to Malkata Palace and the Roman Isis Temple. And if you have the Premium Luxor Pass, you might also want to revisit the tombs of Nefertari or Seti I.

With the Luxor Pass, it’s also worth revisiting Luxor Temple or Karnak over on the east side as well. And while in Luxor, also be sure to set aside a day trip for Abydos and Dendera temples.

***If you don’t have the Luxor Pass, you’ll have to buy the individual tickets at the official ticket offices. These can sometimes be quite far away from the sites themselves. (The Valley of the Kings has its own ticket kiosk.)***

During your visit to Luxor, it’s well worth getting the Luxor Pass if you plan on spending more than a few days there. There are two versions of the pass and both are valid for five consecutive days.

The PREMIUM version costs $200 and allows access to every site in Luxor, including the tombs of Nefertari (1400 EGP) and Seti I (1000 EGP).

The STANDARD pass costs $100 and includes everything in Luxor minus the tombs of Nefertari and Seti I. Together, those tombs cost around $150, so the PREMIUM pass is worth it if you’re interested in seeing them. (Learn more about prices HERE)

Adding up the individual ticket costs of all the attractions I visited in Luxor, I saved a significant amount of money with the pass. The best part, though, was the convenience. The ticket system for sites around the west bank is confusing, with the ticket booths often far apart from the sites themselves.

Without the pass, if you ride past something that looks interesting, you can’t just go in. You’ll have to find the ticket booth and then ride back again. The pass is perfect, then, for those who like to explore.

Furthermore, the pass allows for multiple visits to each attraction. You can visit the expensive tombs multiple times, while photographers can freely return to temples to get optimal lighting conditions.

Note that if you’re coming from Cairo and already have the Cairo Pass ($100 USD), you can get 50% off the Luxor Pass! The deal even works with the PREMIUM Luxor Pass, allowing you to get it for $100!

Considering all that I visited, with both passes I saved over $250 in Cairo and Luxor.

To get the Luxor Pass, you’ll need to bring your original passport, a copy of your passport, a passport photo (exact size isn’t so important) and USD in cash. And be sure to bring your Cairo Pass for the discount.

At the time of writing, the Luxor Pass can only be purchased at Karnak Temple and possibly near the Luxor Museum. (For whatever reason, many locals in the tourism industry don’t seem to know about this pass. Check the Egypt Tripadvisor forums for the most up-to-date information.)

I bought mine at Karnak and annoyingly, the guys at the desk are running a little scam. They claimed that I needed a photocopy of the Cairo Pass even though I had the original. They wanted an extra 200 EGP for them to make a simple photocopy. Just eager to get on with my day, I haggled it down to a 50 EGP ‘fine.’ At least I still got the 50% discount.

I don’t think a photocopy of the Cairo Pass is an actual requirement, and they were probably just making it up. From what I read online, they told other people completely different reasons for why they needed to pay more.

When planning out your Egypt trip, it doesn’t take long to realize how infuriatingly difficult the country can be for independent travelers. The tourism industry has primarily relied on package group tours for decades. For some reason, it seems as if the government doesn’t really want tourists to take public transport. But it’s thankfully still possible.

The easiest way to get from Cairo (or Aswan) to Luxor is by public train. The train from Cairo to Luxor takes about 9 or 10 hours and there are both day trains and night trains. Strangely, the night train (which the government prefers tourists to take) can cost over $100!

Yet the day train only costs a couple hundred Egyptian pounds, or roughly $13 USD. But if you go to the train station and try to buy a ticket in person, they will NOT sell it to you. They will only offer you the expensive night train tickets.

Luckily, even though they don’t sell tickets to foreigners in person, it’s still perfectly legal for foreigners to ride the day trains. The trick is to just buy them online from the official Egyptian National Railways site and print them out before departure.

It seems like you can’t reserve more than a couple of weeks in advance. Furthermore, you will need to create an account on the web site and agree to the terms before searching. If you’re not signed in, the search will turn up blank.

Here is an excellent resource for all train timetables in Egypt. It’s worth going for the nicest AC1 trains, which are still quite cheap. Snacks and coffee are sold onboard. But expect the entire cabin to reek of smoke, as people constantly use the space in between the train carriages as a smoking lounge.

If you’re not able to book online for some reason, here’s another solution: simply show up at the station, hop on the train and sit down. When the ticket inspector comes by, pay him. Strangely, while you can’t buy tickets from the ticket booth, this method is completely acceptable.

In Luxor, the east and west banks of the Nile River couldn’t be more different. The east is the bustling city center where most of the hotels and restaurants are located. This is where you’ll find the train station and the Luxor Museum. And of course, Karnak and Luxor Temples.

The west bank is much quieter and less developed. But overall, the west bank has more tourist attractions. Not only are all the tombs here, but there are plenty of mortuary temples to visit as well. While you can see everything on the east bank in a single day, you’ll need two or three full days to explore everything on the west bank.

That’s why I recommend staying on the west bank. And as the area gradually develops, there are a lot more hotels to choose from nowadays.

Overall, the west bank is pretty spread out. But if you stay close to the ferry port, you’ll get the best of both worlds. Not only will you get a head start on visiting the west bank attractions each morning, but getting to the east side and back will be easy as well.

To really make the most of your time in Luxor, I recommend staying on the west bank, getting the Luxor Pass (see above) and renting a bicycle. You can rent a bicycle for the day from numerous west bank shops at somewhere between 30 – 50 EGP.

I stayed at a place called Sunflower Guest House which was right by the ferry port. The rooms were spacious and clean and I had no issues with my stay. But after my arrival, I discovered that there are plenty of other accommodation options right nearby.

For those who still want to stay on the east bank, Bob Marley Guest House seems to be the most popular place for backpackers. And those with a much bigger budget tend to stay at the Winter Palace.