Last Updated on: 5th August 2024, 11:24 am

Cave houses, stone circles and underground passageways. These are just a few of the things awaiting visitors in the mysterious region of South Armenia, a place where relatively few venture. From the scenic mountaintop Tatev Monastery to Karahunj, one of the world’s oldest astronomical observatories, South Armenia has lots in store to please even the most seasoned of travelers.

Many of those who do visit the region hire a private driver and stay a night or two near Tatev. But I decided to save myself both time and money by taking a one-day tour from Yerevan.

It was a long, exhausting journey which lasted from early morning until around midnight. But it was easily one of my most memorable days in the country.

Tatev Monastery

After over four hours on the bus, we finally arrived at Tatev. And Tatev Monastery, it turns out, is so remote that even the long bus ride wasn’t quite enough. Making it over to the monastery requires a ride on a cable car, locally known as the ‘Wings of Tatev.’

The Wings of Tatev, completed in 2010, happens to be the longest double-track cable car in the world. It was constructed as part of a larger effort to restore Tatev Monastery and promote it to visitors. While people always could, and still can, access Tatev by road, it’s not nearly as exciting as the ropeway.

The ride takes visitors a distance of 5.7 km and lasts around 15 minutes. It’s accompanied by an English narration and some soothing background music.

Just be sure to stand on the left side of the cablecar on the way there, as that’s where all of the landmarks are. I was stuck on the opposite side of the cramped car, but made sure to change sides for the ride back.

Situated atop a basalt plateau, Tatev Monastery overlooks a gorge formed by the Vorotan River. It’s easily one of Armenia’s most scenic monasteries. And that’s really saying something, given all the competition.

The monastery dates back to the late 9th century, though it’s believed that an earlier church existed here from as early as the 4th century. As is the case with many monasteries in Armenia, the spot was also once home to a pagan temple before early Christians destroyed it.

There are a few structures to check out even before the main gate. In addition to an old tomb, you can enter the original Oil Mill. Built in the 17th century, the mill was used to produce vegetable oils like linseed, sesame and hemp. It was deliberately placed outside the walls so people could come and buy oil without bothering the monks.

The oil mill now acts as a mini museum. Rather incongruously, it features informational plaques dedicated to famous Armenian musicians of the 20th century.

Tatev Monastery’s main structure is the Church of Saints Peter and Paul. It’s the oldest structure of the monastery, and it possibly replaced an earlier pre-10th century church. Oriented east-west, it’s an elongated rectangular church which is relatively rare in Armenia.

The interior isn’t nearly as remarkable as the outside. Few of the ancient frescoes survive, and those that do are hard to make out. Looking closely, you might spot relief carvings of Prince Ashot and Princess Shushan, the church’s original benefactors.

Just next to, or south of, the main church is the small St Gregory the Illuminator Church. The original structure was built between 836-848 before being completely destroyed by the Seljuk Turks. After that, it was rebuilt before being destroyed yet again by a 12th-century earthquake.

Given the region’s susceptibility to earthquakes, resident monks came up with a brilliant idea: the Gavazan Column. The column was an ancient seismograph designed to tilt upon sensing a tremor.

Supposedly, it would then automatically shift back into place. Pretty innovative stuff for over 1,000 years ago! But even a functioning seismograph couldn’t save many of the structures from crumbling.

While still standing, the pillar no longer does its job. Erected in 906 by Bishop Hovhannes, it also has a religious significance, having been erected in honor of the Holy Trinity.

There’s still a lot more to see around the complex. Out in the courtyard, you’ll find a plethora of ancient kachkars, or traditional Armenian cross stones. And considering how Tatev Monastery once housed around 1,000 monks and even functioned as its own university, there are a lot of rooms for visitors to explore.

You can check out things like the former bakery, library and Archbishop’s residence. The monastery was not only entirely self-sufficient but was booming economically in its day. In fact, due to the old feudal system, Tatev actually outright controlled dozens of surrounding villages.

Peasants, however, weren’t happy about their land being controlled by the monastery, leading to a few uprisings in the 10th century. Ultimately, they had to be quelled by the local king.

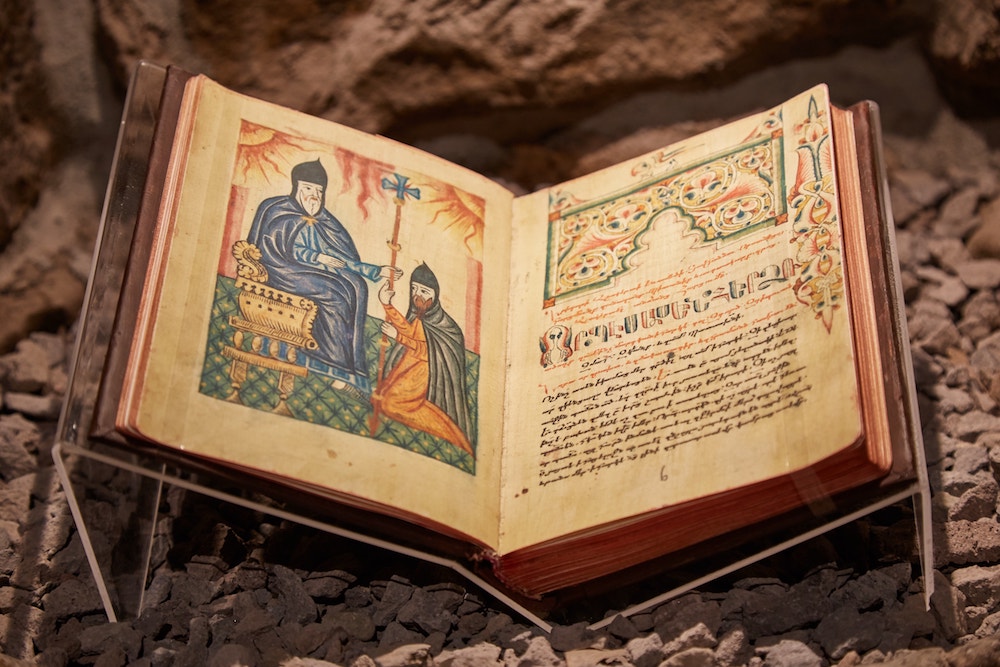

Many artisans also lived here, and Tatev became a thriving center for calligraphy and miniature painting. And from the 14th century, Tatev University was founded by the ruling feudal family, the Orbelians. The university was also instrumental in resisting the attempted Latinization of Armenia by the Roman Catholic Church.

Don’t miss the intricate carvings on one of the doors which clearly evokes symbolism from Armenia’s pre-Christian past. And over in a room near the complex’s edge, notice the large holes in the ground. Supposedly, this is where monks hid treasures and manuscripts during foreign invasions.

After the Seljuk Turks were driven out, Tatev Monastery was largely safe during the Mongols’ incursion into the region. As the Orbelians had promised submission in exchange for the survival of Armenia’s monasteries, Tatev was spared and it even functioned tax-free.

But Tamerlane’s Timurid Empire later demolished it. It was rebuilt but later destroyed again by the Persians in the 18th century. So even during times of peace, the resident monks were probably constantly lying in wait for the next attack.

History and architecture aside, one of the main reasons to come to Tatev is for the views. Various rooms within the complex offer spectacular vantage points of the surrounding countryside and mountains of Syunik Province.

Before heading back to the bus, I took some time to explore a few of the other structures that I’d missed. At the far northern end of the monastery (close to the entrance) is the Surb Astvatsacin Church.

Founded in 1087, it was largely damaged by a 1931 earthquake and had mostly collapsed by the 1960s. Though it was restored in 1980, the dome was at a lower angle than the original, making the overall structure shorter. It was finally fixed in 2018 to perfectly match the original building.

Over to one side, I came across a small museum featuring artifacts recovered during the restoration. Tatev once had its own ‘Matenadaran,’ or manuscript storage room, which lasted from the 10th century up until 1911.

The manuscripts were likely transferred to Russia for safekeeping at that time, before being returned to Armenia upon the opening of the main Matenadaran in Yerevan in 1959.

On the cablecar ride back, I made sure to stand on the more scenic side. The main highlight to look down at is a much smaller abandoned monastery in the middle of the valley. Amazingly, this monastery was connected with Tatev by an underground tunnel network!

Over the centuries, monks would escape here during invasions with sacred relics and manuscripts. It’s considerably far away, however, and this other monastery’s position appears much more vulnerable than Tatev itself.

Khndzoresk

Our next stop was the mysterious cave town of Khndzoresk, also located within Syunik Province and near the city of Goris. Within a large canyon are hundreds of peculiar rock formations. And centuries ago, the rocks were carved out by local residents to use as homes.

Inhabited since at least the 17th century, over 8,000 people once lived in the caves, making Khndzoresk one of the largest villages in this part of Armenia!

That is until the Soviet regime forced them to leave in the 1950s, deeming such primitive housing unsuitable. (Surely they felt their concrete apartment blocks were a major improvement.) Nowadays, the former cave houses are largely used by nearby residents to house livestock.

From the parking area, we walked to a platform from which to take in the excellent views of the cave town. Looking down, we could see a long bridge connecting the two sides of the canyon. And soon we’d be making our way down there to walk across it ourselves.

But before walking across, we briefly stopped in a museum which displays how a typical Khndzoresk cave house would’ve looked like on the inside.

The suspension bridge is 160 meters long and was only completed in 2012. As one might expect, it offers great views of the surrounding canyon. But while it felt sturdy enough, I was relieved to make it to the other side and walk on solid ground again.

We walked along a trail taking us through the lower level of the village. We passed by numerous manmade caves in addition to some multistory abandoned brick buildings.

Walking past more caves and through a dense forested area, we arrived at Khndzoresk’s main church, St. Hiripsime, established in the 17th century. It was a far cry from the elaborate and imposing structures we’d just seen at Tatev Monastery.

While still in use among the local community, the church lacks the funds for proper repair and restoration. One corner of the room contained a large pile of rubble accumulated from earthquake damage. Regardless, St. Hiripsime Church maintains its rustic and cozy atmosphere, making it feel like you’ve just stepped into another time period.

Walking past some donkeys hanging around outside, we made our way back the same way we came. While our time at Khndzoresk was rather brief, I’d like to come back here for longer should I visit Armenia again.

Notably, there’s a very similar looking town called Kandovan outside of Tabriz, Iran, just across the border from Syunik Province. And if you like ancient cave towns, there are plenty of interesting ones to check out in nearby Georgia and Turkey.

Karahunj

Just as the sun was beginning to set, we hopped off the bus to explore one of Armenia’s oldest and most mysterious locations. Located near the city of Sissian, Karahunj, also known as Zorats Karer, is believed to be one of the world’s oldest astronomical observatories.

In fact, the site could even be as old as 7,500 years, placing it 4,500 years before Britain’s Stonehenge. That’s just an estimate, and the site could potentially be even older. Could the stones have been placed around the same time as Egypt’s predynastic Nabta Playa observatory?

In total, there are 223 basalt stones at Karahunj, with some weighing up to 10 tons. Archaeologists have also discovered Bronze Age artifacts at the site, like bronze swords and bead fragments.

At first, Karahunj appears to be little more than an old, crude monument of some sort. Yet the further you walk, the more it becomes apparent that many of these stones were placed deliberately. But for what?

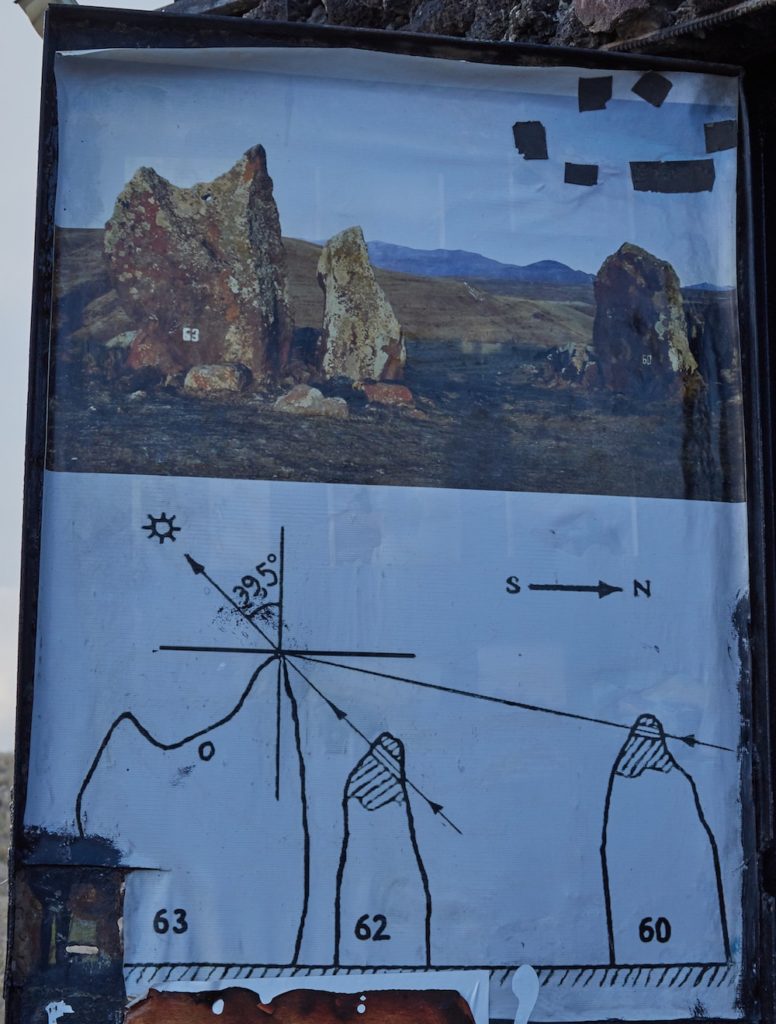

Due to a lack of funding, there’s still a lot of research yet to be done at Karahunj. But so far, 17 stones have been determined to be aligned with the setting or rising of the sun on solstices and equinoxes. And 14 are aligned with lunar movements.

Notably, both Karahunj and Stonehenge have an opening passageway toward the northeast, defining the sunrise on the day of the summer solstice.

What’s more, is that people like Vachagan Vahradyan of Russian-Armenian University have pointed out that some stones seem to have been placed to represent the vulture-shaped constellation of Cygnus.

Interestingly, the central section of Karahunj features a large amount of smaller rocks surrounding a pit in the center. It seems to have been some sort of burial chamber, leading skeptics to claim that Karahunj was a graveyard and nothing more.

But the area could’ve been utilized by various prehistoric cultures throughout the ages. While Karahunj may have been used for burials, that doesn’t mean that this was always its original purpose.

Even more mysterious still are the cleanly cut holes in many of the rocks. Archaeastronomers have determined that many of these holes help the observer see certain phenomena or constellations in the sky on particular days. If that wasn’t amazing enough, one wonders how such precise holes were made in the first place?

Around 80 of the stones at Karahunj have holes in them, most of which are between 5-8 cm in diameter. I’m no geologist or stonemason, but basalt is known to be an especially hard stone. It’s very difficult to cut without even harder stones like diamonds.

Were the builders of Karahunj using similar tube drilling technology to what the ancient Egyptians used?

I walked over to the edge of Karahunj which overlooks the Dar River canyon. Then, looking back, I noticed that almost the entire group was already gone. Checking my watch, I had only a couple minutes to make it back to the bus before departure time!

I hurriedly snapped some additional photos of Karahunj as I speed-walked back to the parking lot, making it just in time.

While my time at Karahunj was brief, it certainly left an impression on me. And I have a strong feeling that our current knowledge of the site barely scratches the surface.

Additional Info

I went on the tour mentioned above with One Way Tour. I paid only 8,000 AMD for the entire trip, though the ‘Wings of Tatev’ cableway cost 7,000 AMD for the roundtrip journey. The ropeway is optional, and if you don’t want to pay you can get to the monastery by bus.

At the time of writing, One Way seems to be the only tour company which offers the combination of Tatev Monastery, Khndzoresk and Karahunj. Other companies seem to just offer Tatev combined with Noravank Monastery.

Visiting the three locations within a single day from Yerevan is pretty extreme for a day trip. We departed at 7:30am and didn’t make it back to Yerevan until just before midnight! And all that for just three locations. But as a solo traveler, I felt it was definitely worth it.

If you’re traveling as a couple or a group, you may want to consider paying a private driver for 2 days and spending the night at a hotel somewhere near Tatev. I met a group at my guesthouse who’d done this. And they also had extra time to visit a place called Devil’s Bridge, which they highly recommended.

But as I was traveling solo and also wanted to fill up my remaining days in the country with other excursions (there’s a lot more to do in Armenia than people think!), I opted for the day tour.

Traveling with One Way Tour was an overall positive experience. Everything was smoothly run and the guide was friendly and informative. And the long bus rides provided a good opportunity to get to know the other travelers. From my experience, most of those visiting Armenia tend to be well-traveled and rather interesting people.

If there was one complaint about the tour, it’s that despite the long journey, we only had one stop for breakfast (around 9 or 10am) and no stops for lunch or dinner. Furthermore, we couldn’t eat on the bus. So we had to buy food for the day in the morning and hastily eat it before getting back on the bus.

For whatever reason, accommodation prices in Yerevan are considerably higher than those of nearby Tbilisi. This is in spite of most other things, like food and transport, costing the same amount. If budget isn’t an issue for you, then you should base yourself in the city center (within the circle or just outside of it).

Yerevan makes a great base from which to explore many other parts of Armenia. If you’re doing an extended stay in the city and want to save some money, staying outside the center will be fine. Just make sure that you’re within close distance of a metro station.

I stayed at Glide Hostel which I’d highly recommend for budget travelers. I opted for the private room with a private bathroom, but they also have some shared bathroom and dorm options available.

The guesthouse is located about 5 minutes on foot from Baregamutyun Station, the northernmost metro station. But you can still walk to the city center in about 30 minutes if the weather is nice. The staff were friendly and helpful, and a tasty breakfast was provided each morning.

As Armenia’s borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan are closed, most visitors enter the country overland from Georgia. And from Tbilisi you have a couple of options.

You can take a minubus from Ortachala Station or from outside Avlabari Station. Additionally, shared taxis depart from outside the central railway station. Prices will vary depending on the transportation method, but expect to pay around 20 GEL for the minibus and up to 50 GEL for a shared taxi.

The ride typically lasts 5-6 hours. There will usually be at least one vehicle departing per hour. But rather than a set schedule, most drivers will wait until the vehicle fills up. Typically, you’ll be dropped off at Yerevan central bus station Kilikia, from where you’ll need to take another bus or a taxi to get to the city center.

Not being a fan of long minibus rides, I opted for the train instead.

The only train option is a night train (train 371) which departs at 20:20 at arrived at 6:55. Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to buy tickets online, as you’ll need to navigate through a web site that’s only in Russian. To make matters worse, the site is unsecured. It’s best to buy tickets in person at least a few days in advance at Tbilisi Central Station. Be sure to bring your passport.

I got a second-class ticket for around 90 GEL – considerably more expensive than the prices I’d read about online. I was in a cabin with three other travelers but we had enough space and it was fun chatting and sharing snacks up until it was time to go to bed. Unlike my prior night train experience to Zugdidi, this time we got sheets. Be sure to bring earplugs in case someone’s traveling with an infant!

Supposedly, during non-peak months (late September – mid-June), the train only leaves every other day. While I’d read that it only departs on even-numbered days, I asked if they had a ticket for the 17th, and they said yes. I didn’t inquire further, and am not completely sure how the system currently works.

The train is both slower and more expensive than the other options. However, it’s the easiest and most straightforward when it comes to passing through immigration. Normally, immigration officers at both sides of the border will come on the train to check your passport. No need to wait in line with all your luggage. While I did have to get off the train and line up at a booth while leaving Georgia, it only lasted a couple of minutes.

Upon arrival in Yerevan, you’ll encounter an ATM, and the central railway station is connected to the metro. There aren’t any SIM card vendors in the station so be sure to print out or pre-load your accommodation info on your phone. I later got a SIM card at the Beeline shop on Northern Avenue.