Last Updated on: 3rd January 2020, 07:31 pm

Walking up the steep dirt path, I stopped to look at a vulture flying over the otherworldly desert landscape. Meanwhile, a large lizard, seeking shade, dashed across a nearby pile of rocks. I was on my way to see some religious frescoes painted by cave-dwelling monks who once lived here centuries prior. But first, I had to make my way past the groups of soldiers equipped with large guns. This certainly wasn’t your everyday hiking experience, I realized. But it’s this strange mix of gorgeous scenery, religious heritage and an ongoing border dispute that makes the David Gareja Cave Monastery one of Georgia’s most intriguing destinations.

The monastery complex is divided into two main sections: the Lavra Monastery and the Udabno Monastery, which is actually situated in Azerbaijan. For years, visitors have been allowed to freely walk to the Udabno portion to see the caves and ancient frescoes. But due to ongoing disagreements between the two countries, the Udabno Monastery has been off-limits to visitors for most of this year.

Luckily for me, I happened to get there on a rare day that Udabno was accessible. It had been closed off just the week before, and access would be restricted again not long after my visit. As the situation is constantly changing, be sure to check online before your trip so you don’t end up disappointed. With that said, the main active monastery, along with the views of the surrounding countryside, make for a worthwhile day trip from Tbilisi regardless.

Getting To David Gareja

The David Gareja Cave Monastery (also commonly called Davit Gareja or Gareji) is located in Georgia’s eastern Kakheti region, around 70km from Tbilisi. While there are no public buses to get there, there’s an excellent solution for those not keen on shelling out money for a private driver.

A company called Gareji Line departs from Tbilisi daily at 11am (from April 1st – October 31st only) for only 30 GEL. It’s not exactly a tour, but more like ‘organized group transport.’ Visitors get to explore the main site freely on their own, though there is a set schedule which includes a stop for dinner in a nearby village. (Learn more about visiting with Gareji Line down below).

The ride lasts around two hours each way. In addition to a short break at a rest stop (there’s no food or water at the monastery itself), we also briefly stopped somewhere near Kapatadze Lake to take in the scenery.

The rolling green pastures could’ve been the scene of the classic Windows ’95 wallpaper, while one side was dotted with hundreds of sheep. But these views wouldn’t be able to compete with what we were about to see at David Gareja.

The Lavra Monastery

The first stop past the parking lot was the ancient Lavra Monastery, founded by David Gareja himself in the 6th century AD. But just who was he?

David Gareja was one of 13 Holy Assyrian Fathers who came to Georgia from Mesopotamia to strengthen Christianity – or so the legend goes. Georgia had already adopted Christianity as its national religion as early as the 4th century (second only to Armenia), but the Assyrian Fathers further bolstered the religion by establishing numerous monasteries.

Aside from David Gareja, twelve monasteries named after the other Assyrian fathers can still be visited throughout the country, but none in such a spectacular setting as this.

While featuring many of the structures one would expect to find at an Orthodox monastery in Georgia, Lavra is remarkable for the gigantic diagonal rock that looms over the rest of the complex.

Numerous rooms have been carved out of its side, though visitors can only appreciate them from afar. This unique blend of shapes makes Lavra appear as a strange cross between a traditional monastery and a building designed by Gaudi.

Presently, Lavra is an active monastery inhabited by a community of monks. And during your visit, you can even step into the Chapel of Resurrection which contains the tombs of David Gareja and his disciples.

Yet throughout much of the 20th century, the monastery was left abandoned at the command of the Soviet Union. The monastery had already survived pillage by the Mongols and in 1615, the murder of 6,000 monks by Persian Shah Abbas. But it was finally the Bolsheviks who succeed in keeping monks away from David Gareja.

After exploring the various sections of Lavra Monastery (at least those that were accessible to visitors), I made my way up to the watchtower, an 18th-century construction. There, I was granted with an excellent view of the complex down below. But looking behind me, I could see that there was plenty more to explore.

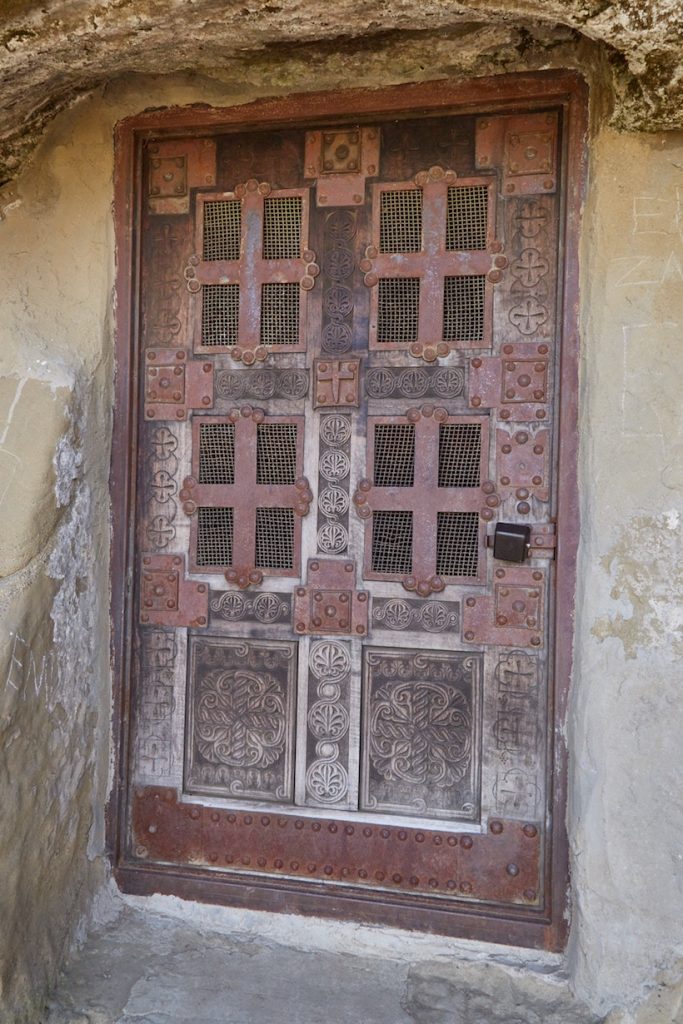

Noticing a staircase carved into the side of the mountain, I was curious to see what it was. While inaccessible to visitors today, behind the locked door is a natural spring which early monks of David Gareja relied on for survival.

In the 6th century, and in the centuries to follow, resident monks had to painstakingly carve paths in the cliffside to create an irrigation system from scratch. Today, the spring is appropriately called ‘David’s Tears.’

Additionally, you can also see little holes they dug out to better walk up and down the slippery rock. From afar, they look like footsteps imprinted by a mythical giant.

Atop the Mountain

Arriving at the top of the hill, I took in the stunning panoramic views of the surrounding landscape. But I was far from alone. At the top with me were other tourists cheerfully snapping selfies, groups of Georgian nationalists chanting political slogans, and armed soldiers from both Georgia and Azerbaijan keeping careful watch over the situation.

While part of the David Gareja complex belongs to Azerbaijan, Georgians argue that the entirety of the monastery had been theirs for centuries. Unfortunately, the conflict seems largely due to the Soviet Union’s total disregard for history, cultural heritage and ethnicity when marking the borders between Soviet republics.

Though the USSR is no more, Azerbaijan remains adamant about holding onto the land it had been previously awarded, including the Udabno Monastery and chunks of historical Armenia (though that’s a different story for another time).

As Azerbaijan is a majority Muslim nation, Georgians can’t understand why the government won’t simply grant them the remainder of David Gareja in a land swap. But according to Azerbaijan, the land was once controlled by Caucasian Albania (no relation Balkan Albania), modern Azerbaijan’s predecessor.

I walked past the ‘Chapel of Resurrection,’ outside of which more people were starting to gather, and made my way across the ridge of the mountain. From here I was rewarded with breathtaking views of two countries at once. And during my trek, I couldn’t help but recall another ancient mountaintop temple at the heart of a border dispute, Preah Vihear.

Eventually, I reached an area where a group of Georgian soldiers were casually smoking cigarettes seated atop some rocks. Clearly, I couldn’t proceed any further, and at some point I’d missed the caves of Udabno.

Fortunately, the helpful soldiers pointed me in the right direction. Walking down the path, which descended and curved around to the other side of the mountain, I suddenly received an SMS on my phone: ‘Welcome to Azerbaijan.’

The Udabno Monastery

Construction of the Udabno Monastery began a few centuries after the establishment of Lavra. From the 8th-10th centuries, dozens of caves were carved out of the sandstone cliffside. The monks would heat the rock with fire before pouring water over it, causing the rock to expand and split.

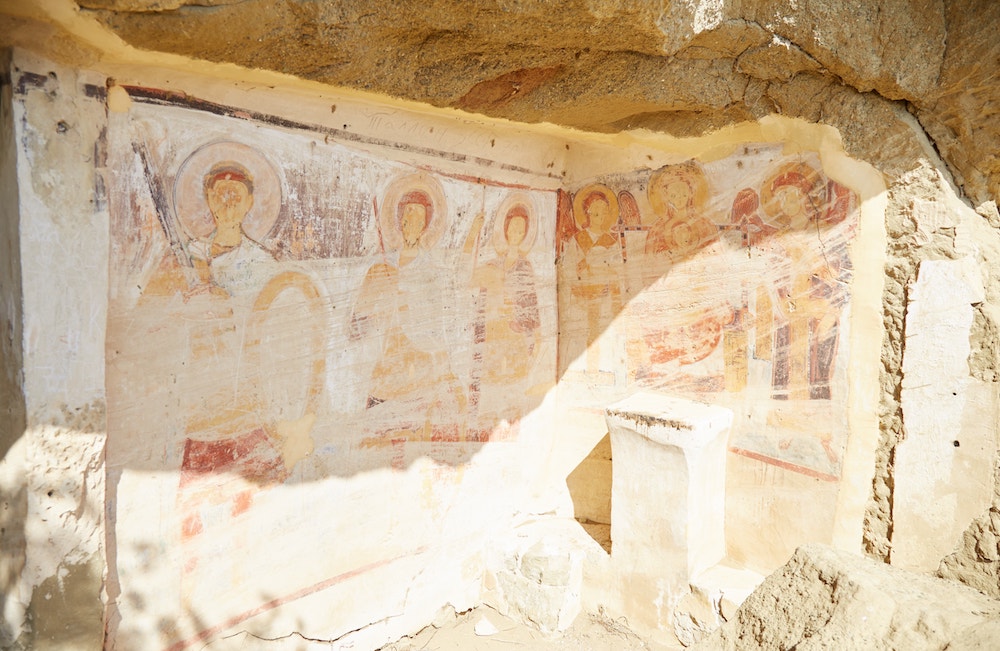

Thanks to its colorful frescos, many of which are one of a kind, Udabno is widely regarded as the most important section of the David Gareja Cave Monastery. But even after surviving both Mongol and Persian sackings, they barely made it out of the 20th century.

As the area somewhat resembles Afghan terrain, Soviet troops used the monastery as training grounds for their war there. Sadly, parts of the Udabno Monastery were permanently damaged (seemingly deliberately so) during the drills. And training at the spot only came to a halt due to fervent protests by enraged citizens.

Surprisingly, however, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgian troops themselves used the area for training. Yet again, an uproar put an end to the practice, but not until the year 1997. With all things considered, the Azerbaijani government should at least be commended for taking good care of Udabno, even designating it as a cultural heritage site.

The frescoes of Udabno remain some of the finest surviving examples of medieval Georgian art. In addition to numerous Biblical scenes, many important Georgian historical figures have been immortalized in the works.

Many of the frescoes date back to the 13th and 14th centuries. And they remain in pretty good condition considering the circumstances, both natural and historical.

During my explorations, I encountered well over a dozen caves. Many of the more interesting ones took some effort to reach, and there are many more trails around the area than first meets the eye. Considering how many of the caves aren’t even visible from the main path, there were surely lots more that eluded me.

The caves ranged from humble single-room dwellings to elaborate structures large enough to fit small congregations. Most other visitors that day had already finished exploring Udabno by the time I got there, meaning I had them mostly to myself.

I couldn’t help but wonder what life would’ve been like living in such an unusual and isolated location. But it’s unlikely that the monks would’ve ever tired of the view.

I eventually made my way back to the Chapel of Resurrection. The group of nationalists had grown and were becoming increasingly vocal. While things wouldn’t escalate on the day of my visit, sometime later, a Georgian nationalist would even grab one of the Azeri soldier’s guns!

Checking the time, I realized I’d have to hurry if I was going to make it back to the bus in time. I hastily, yet carefully made my way back down the slippery path, arriving at the parking lot with just a few minutes to spare.

Additional Info

As mentioned above, the David Gareja Cave Monastery can be reached with a transportation service called Gareji Line. It’s not a group tour, but more like organized transport with a set schedule. It only costs 30 GEL roundtrip and departs every day between April 1st and October 31st.

Gareji Line can’t be booked in advance and you can only pay in cash on the morning of your trip. The bus leaves from Pushkin Square (just nearby Liberty Square) at 11am, so it’s best to get there a bit early to ensure there’s a spot for you.

The bus arrives at David Gareja at around 14:00 and leaves at 16:30. The bus driver is unlikely to speak English, but the company conveniently passes out small brochures with the itinerary printed on them.

After leaving the monastery, everyone will stop in the village of Udabno (not to be confused with Udabno Monastery) for dinner. You’ll encounter two restaurants with nearly identical menus and prices. While slightly pricey by Georgian standards, the food was pretty good.

Arrival back in Tbilisi occurs at around 20:00 at night.

If you want to visit David Gareja out of season, you’ll have to go as part of a group tour or hire a private driver. Or, you may even choose to drive there yourself. But keep in mind that since the roads leading up to the monastery complex are horrible, a 4×4 is recommended.

The David Gareja Cave Monastery complex is just one of three major ‘cave towns’ in Georgia, the others being Uplistsikhe and Vardzia. Therefore, if you’re unable to visit the Udabno Monastery and have limited time in the country, you may want to visit one of the other sites instead.

The histories of all three sites are quite different. Uplistsikhe was an ancient pre-Christian temple that thrived as a pagan center of worship for centuries before later being converted to a Christian one. And Vardzia, the ‘newest’ of the three, was an entire town carved into the rocks in the 12th century. Most notably, it was inhabited by one of Georgia’s most important historical figures, Queen Tamar.

Despite being the most overlooked of the three, I’d have to say that Uplistsikhe was my personal favorite, given its unique appearance and interesting history. But if time allows, all three Georgian ‘cave towns’ are definitely worth visiting.

Though located in the Kakheti region, most visit the David Gareja Cave Monastery as a day trip from Tbilisi. Despite Georgia being such a small country, Tbilisi is a bigger city than most would expect, and visitors have a number of neighborhoods to choose from within the city center.

Many tourists choose to stay in the ‘Old Tbilisi’ area, and for good reason. This area is home to many prominent landmarks like the Turkish baths, Rezo Gabriadze Marionette Theater, Narikala Fortress and the Botanical Gardens. You can also walk across the river to access Sameba Cathedral (located in Avlabari, another interesting area), while Liberty Square is a short walk to the north.

Many visitors also base themselves near Liberty Square and along Rustaveli Avenue. This area would also give you access to some of Tbilisi’s most notable architecture, such as the Parliament Building, along with numerous museums. Furthermore, the bus to David Gareja departs from Pushkin Square, just next to Liberty Square.

Further north, on the eastern side of the river, Marjanishvili is another popular area. From here you can easily walk to Agmashenebeli Avenue, known for its architecture and restaurants. Also nearby is Fabrika, a unique multipurpose space which features a hostel, art spaces, bars and restaurants.

An increasing number of visitors are also basing themselves in the city longer term. In that case you should also consider the Vera and Saburtalo neighborhoods.

For whatever reason, many Tbilisi residents recommend the Vake district, but I would advise against staying there. While it may have some trendy cafes and Vake Park, it’s the one neighborhood in central Tbilisi with no metro access. Furthermore, the neighborhood is very hilly with an atrocious traffic problem (even by Tbilisi standards!). Off the main streets, there are few traffic lights or underpasses, while entire sidewalks are often blocked by parked cars. With all that considered, it’s best to stick to one of the other neighborhoods mentioned above instead.