Last Updated on: 2nd April 2020, 08:15 am

In the Samtskhe-Javakheti region of southwestern Georgia, the unassuming town of Akhaltsikhe is home to one of the country’s most unique – and also controversial – ancient fortresses. But perhaps ‘ancient’ isn’t the right word to describe Rabati Castle. Despite being over 1,000 years old, much of what visitors encounter today was hastily constructed in 2011. While feelings about the attraction may be mixed, Rabati Castle also happens to house one of the country’s finest collections of archaeological artifacts.

When Rabati Castle was first established in the 9th century, Akhaltsikhe (which means ‘new fortress’) was part of the kingdom of Tao-Klarjeti. It was then absorbed into the Kingdom of Georgia in the 1000’s, and it withstood an invasion from Tamrlane’s Timurid Empire in the late 14th century.

Centuries later, Akhaltsikhe was absorbed into the Ottoman Empire who administered it for hundreds of years. And eventually, the Russian Empire invaded and returned the territory to Georgia in the 1800’s. It seems like whoever redesigned Rabati Castle drew inspiration from this complicated mix of influences, giving the fortress its rather incongruous, albeit unique appearance.

Entering Rabati Castle

Situated on a hilltop, the huge fortress is visible from most of Akhaltsikhe. To get there, I walked through a small tourist district, full of hotels and restaurants, located at the base of the hill.

Walking further uphill, Rabati Castle’s imposing walls came closer into view. Though I’d visited several ancient fortresses in Georgia before, none of them compare to Rabati in terms of grandeur.

But upon my first glimpse of the interior, I became a little confused.

Admittedly, my initial impression of Rabati Castle wasn’t great. While I was expecting a slightly refurbished historical fortress, what I first encountered was a poorly constructed, Disney-esque reimagining.

Some of the newer towers and walls were obviously built of cheap concrete blocks, and I felt as if I were inside of a massive Lego play set. The place seemed like something designed for the background of a movie scene, but never meant to be examined up close.

After buying the admission ticket (which is only checked upon entry to the Upper Citadel), I started my explorations by turning left. There’s little of note here historically or architecturally. But the tower at the edge of the fortress provides some excellent views.

As cheap as they may appear, every tower I encountered at the castle was climbable. And they all provided great views of the surrounding town and mountains. From the tower, I could also get a better sense of the scale of the rest of the complex. Clearly, there was still much to explore.

The Upper Citadel

Entering the Upper Citadel, I passed through a corridor which revealed the striking difference between the original fortress and the newly constructed version. If Rabati Castle were to be left untouched for the next couple hundred years, it’s clear which side would hold up better.

Fortunately, things would improve as I ventured deeper into the citadel. And gradually, Rabati Castle would even start to grow on me. I encountered well-manicured gardens and numerous secret passageways which take visitors up to some hidden vantage points.

Reaching the central area of the Upper Citadel, the Ottoman influence became more apparent. I approached what appeared to be a traditional Ottoman-style courtyard, featuring some small pools of water entirely decorated in intricate mosaics.

The centerpiece of Rabati Castle is arguably its mosque. While the Ottomans took control of Akhaltsikhe and Rabati Castle from the 16th century, they didn’t build the gold-domed mosque here until 1752.

What we see today was largely rebuilt during the recent restorations, but that’s not so easy to tell from the structure’s interior.

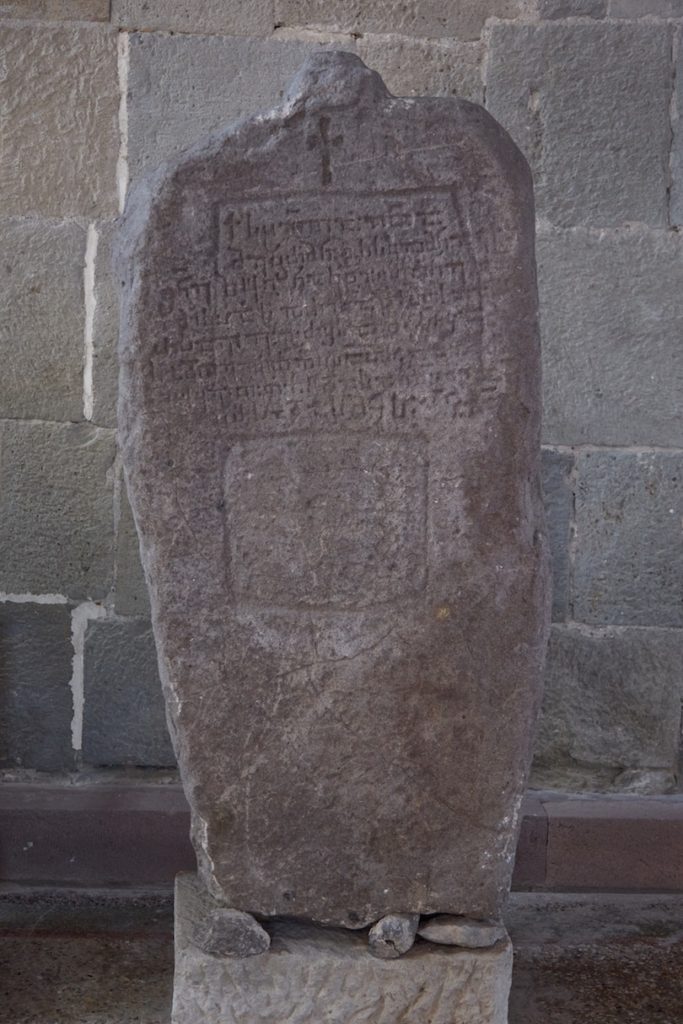

On display throughout the mosque are various artifacts, seemingly Christian in origin, that were uncovered during recent excavations.

I wondered if the mosque was still perhaps active. But my question was quickly answered when I saw a tourist bring a dog inside without any objections from his tour guide!

Sadly, Rabati Castle lacks any informational signage whatsoever. And many of the noteworthy structures and pavilions have been left unmarked on the large map at the entrance.

Rabati Castle, then, is best not approached from a historical or educational perspective. Instead, think of it as a nice park and gardens complex with a few neat structures scattered about.

History lovers aren’t completely out of luck, though. Despite being hardly promoted, the Upper Citadel of the fortress contains the Museum of Samtskhe-Javakheti, one of the best historical museums in all of Georgia.

But first, I made my way up the tallest tower at the far end of the complex. This tower appears older than the more recent concrete constructions. And it also offers more fantastic views of the fortress and town down below.

Museum of Samtskhe-Javakheti

The Museum of Samtskhe-Javakheti requires a separate entry fee of 7 GEL (closed Mon.) but it’s well worth it. Inside, you’ll find a plethora of artifacts discovered in the nearby Meskheti region from as far back as 4,000 BC.

It was from this time, until around 2,000 BC, that much of the Caucasus were inhabited by what scholars now call the Kura-Araxes civilization. In Meskheti, Kura-Araxeans dwelled in flat-roofed homes, of which there’s a model to greet museum visitors upon entry.

The homes were mostly built of stone and had wooden roofs. And they also doubled as places of worship, as Kura-Araxean families would carry out rituals for the Sun goddess at the hearth in the center of the room.

Also on display at the museum, you can find an assortment of pottery, altars and incense burners from a typical Kura-Araxean home. Another noteworthy vessel features pictograms which scholars believe to be a very early attempt at writing.

Among the most refined and beautiful artifacts on display at the museum are these bronze disks. The highly intricate disks represented the local Sun deities and were worn by priests at the time of their burial. Amazingly, the pieces are as old as the 15th century BC.

Also on display were numerous other artifacts representing local deities, in addition to remnants of ancient weapons, such as axes and arrowheads. There were also a plethora of urns dating from the 8th – 6th centuries BC, which demonstrate a strong influence from the neighboring Hittite culture.

Additionally, the museum contains numerous goods that came from other regions, such as Syria and Egypt, from around the 1st century AD. At the time, the Samtskhe-Javakheti region was a common stop on cross-regional trade routes.

Also on display was a miniature altar inspired by the Zoroastrian Sassanian Empire of Persia. Before the formal adoption of the Christianity as the national religion, Iranian religions like Zoroastrianism and Mithraism were popular in Georgia, and one of the altars here dates back to the 4th century AD.

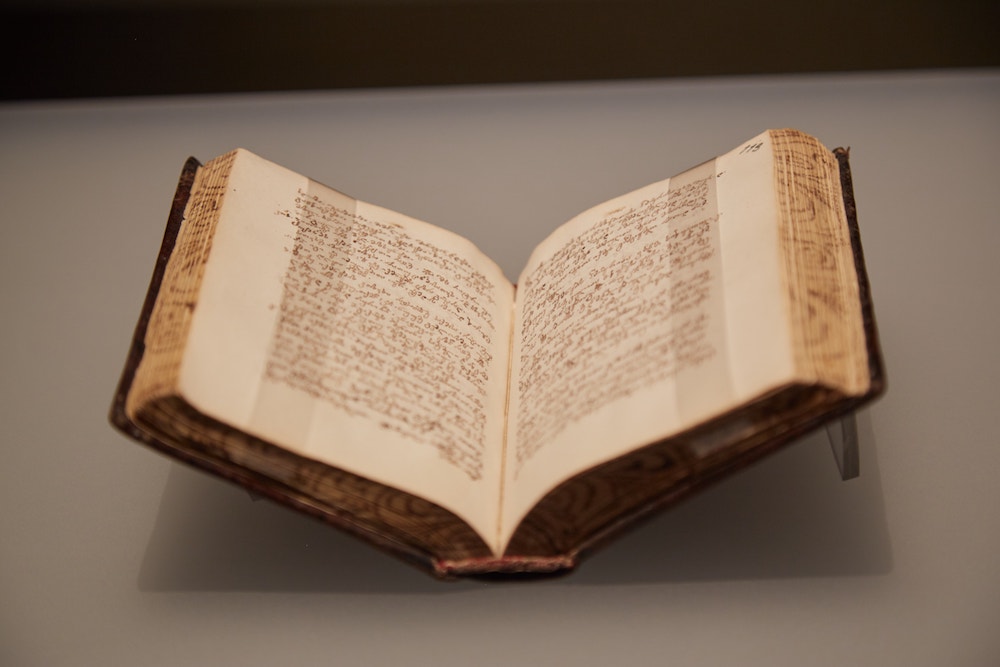

Remarkably, the museum also contains the oldest surviving fragment of the Georgian epic poem ‘The Knight in the Panther’s Skin.’ While the poem, authored by Georgian national poet Shota Rustaveli, was written down in the 12th century, this copy supposedly dates back to the 1500s.

And the museum contains plenty of artwork from Georgia’s Christian era, including frescoes from 1,000 years ago. Some of the paintings even come from the main cathedral of the nearby cave city of Vardzia.

Georgia, of course, remains an Orthodox Christian nation. So unlike the ancient artifacts of the prior civilizations like the Kura-Araxes, you can easily see old Christian frescoes by simply walking into a church.

Also within the museum are some artifacts from the Ottoman era. But given the overall Ottoman theme of Rabati Castle itself, the selection is surprisingly small.

All in all, the unexpected gem of the Museum of Samtskhe-Javakheti helped compensate for the overall disappointment of Rabati Castle. But note that while Rabati alone might not be worth coming all the way to Akhaltsikhe for, it’s just one of several highlights in the general area.

Akhaltsikhe also serves as a great base for visiting places like Vardzia and the tranquil Sapara Monastery.

Additional Info

While there are some organized day tours which leave from Tbilisi, staying at least a night or two is recommended considering all that there is to see. Luckily, getting to Akhaltsikhe by public transport is simple and easy.

In Tbilisi, take the metro to Didube station and then follow the crowd to the large bus station/outdoor market hybrid. It’s not really a proper station, but just a bunch of vehicles parked within a huge parking lot.

There are marshrutkas (minibuses) for Akhaltsikhe that depart whenever full. While Didube mostly lacks signage, just ask someone where the bus is for Akhaltsikhe (both kh combinations in the name make a gutteral CH sound). If Akhaltsikhe is too hard to pronounce, you can ask about Borjomi, as the same marshrutka stops there along the way.

From Tbilisi, a one-way ride takes 2-3 hours and costs 10 GEL. You can just pay after boarding the bus.

Akhaltsikhe is also reachable by marshrutka from cities like Borjomi and Kutaisi.