Last Updated on: 16th October 2024, 07:32 pm

Diyarbakır has long been considered a prized possession of the many kingdoms who managed to control it. Due to its strategic location along the Tigris River, it’s been continuously inhabited for thousands of years. And it’s now one of the most historically and architecturally rich cities in Turkey. In the following Diyarbakır guide, we’ll cover the main things to see and do in what’s arguably Turkey’s most underrated city.

This guide largely focuses on the walled Old City area, also known as Sur. All of the attractions can be reached on foot and two full days in the city should be plenty. For more information on transport and accommodation, check the very end of the article.

Diyarbakır: A Brief History

Diyarbakır, located in the northern part of Mesopotamia and the Fertile Crescent, has a history as old as human civilization itself. Some of the world’s earliest Neolithic settlements, in fact, have been discovered within the province.

Evidence suggests that Diyarbakır’s current city center, meanwhile, has been settled since at least the 5th millennium BC.

A couple thousand years later, the Hurrians, contemporaries and rivals of the Hittites, built a settlement at the Amida Höyük mound, now in Diyarbakır’s citadel.

Later, the city found itself at the frontier of battles between the Romans and the Persians. And Diyarbakır’s defining feature – its towering city walls – originally date back to this time. They were erected in the 4th century AD by Roman Emperor Constantius II.

Diyarbakır means the ‘City of Bakr,’ referring to Banu Bakr, the Arab tribe who conquered it in 639. They did so under the reign of Umar, one of the earliest Islamic Caliphs who also conquered much of Persia and Byzantium.

The city has remained majority Muslim ever since, and all successive kingdoms to control it over the years were Muslim as well.

The city was then dominated by the Umayyads, the Abassids, the Hamdanids, the Marwanids, and the Seljuks, among others.

It was later ruled by the Ayyubids, the Artukids and then the Akkoyunlus, or White Sheep Turcomans. In the early 1500s, it was conquered by the Safavids before finally being taken over by the Ottomans.

And throughout Ottoman history, Diyarbakır prospered as one of the most important cities of the empire – both culturally and militarily.

Though the city long had a diverse population, including many Assyrian and Armenian inhabitants, Diyarbakır is now overwhelmingly Kurdish.

In fact, with nearly 2 million people, it’s the largest Kurdish-speaking city in the entire world.

What is Kurdistan?

Diyarbakır is often nicknamed the ‘unofficial capital of Kurdistan.’ But what exactly does that mean?

The Kurds are an Indo-European ethnic group native to parts of Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria. They have a global population of around 30 million, but Turkey has the largest number of Kurds by far, with around half the total population.

Most Kurds in Turkey are concentrated in the east and southeast parts of the country, sometimes referred to as Turkish Kurdistan. And Diyarbakır is the largest and most important city in this region.

The Kurds, traditionally a nomadic people, have long sought to establish their own country. Over the course of history, various powers have used the Kurds to do their dirty work while promising them a homeland in return. But to this day, none of these promises have been fulfilled.

From the 1920s, since the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, there have been numerous Kurdish separatist rebellions – all of them violently quelled.

More recently, terrorist groups like the PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party) have emerged. For the past 30 years, they’ve been waging war on the Turkish military and innocent civilians alike.

In 2016, fighting flared up between the two sides in Diyarbakır. A curfew was imposed on the city in an attempt to seek out suspected militants, and much of the Old City was destroyed in the turmoil. Tragically, hundreds of civilians also lost their lives.

Fortunately, as of 2020, the security situation is stable and the damaged part of the city is currently being rebuilt.

The PKK, of course, does not represent most Kurds, including other Kurdish nationalists.

Presently, the closest thing to an official Kurdistan is the semi-autonomous northern half of Iraq, or Iraqi Kurdistan. But since the Kurds are present in four different countries, creating a single unified state is no simple task.

To make matters even more complicated, ‘Greater Kurdistan’ also overlaps with ‘Greater Armenia’ and ‘Greater Iran.’

With that said, not all Kurdish nationalists have such an ambitious goal in mind. Many simply want more rights and autonomy within their current countries.

During your travels around east and southeast Turkey, you will hear the word ‘Kurdistan’ used quite a lot. Sometimes it’s merely used in a geographic sense, but often politically as well.

It’s best to avoid using this term in other parts of the country, however. It’s considered a taboo word that can even still get Turkish citizens into trouble.

As a foreign visitor, you will find the Kurds to be incredibly warm, welcoming and hospitable – especially if you’re a Westerner, as the Kurds have long considered the West to be an important ally.

The Citadel

The entire walled city of Diyarbakır could be considered as one big fortification. But the area known as the Citadel has long functioned as a fortress within a fortress. Known locally as Iç Kale, the ancient castle was established around the city’s very first prehistoric settlement.

Before the entrance to the Citadel, which is located in the northeast part of the Old City, you’ll find a well-manicured park where locals come to relax.

Also around here is a staircase leading to the top of the city walls, and you can climb up for amazing views of the Mesopotamian plains. From here, you can also see the part of the city that was destroyed in 2016 and is now being rebuilt.

For those wishing to walk atop the walls, that’s best done on the opposite side of the city, which you can read more about below. This area is also the start of a scenic walking trail just outside the walls, taking you all the way to Keçi Burcu.

Once you’re ready to go inside, walk toward the towering minaret of the Prophet Süleyman-Nasiriye Mosque.

Just next to it, you’ll notice an arch which leads to the inner portion of the Citadel. It was built by the Artukids, Turcoman vassals of the Seljuk Empire, in the early 12th century.

The Artukids also built an elaborate palace within the Citadel as well as a school which would become an important scientific center in its day.

Prophet Süleyman-Nasiriye Mosque

Before exploring the Citadel, you can step into the Prophet Süleyman-Nasiriye Mosque, also built by the Artukids in 1160. Within the mosque are no less than 27 tombs. They belong to Muslim soldiers who died while trying to overtake the city from the Byzantines in the 7th century.

The basalt mosque also houses the tomb of Hz Süleyman, the man who led the military campaign. As this was so early on in Islamic history, many of those entombed here were companions of the Prophet Muhammad himself.

Exploring the Citadel Area

Entering the Citadel requires a ticket which, as of 2020, only costs 10 TL. That’s an incredible bargain considering all there is to see inside, including a few museums and an ancient church.

A major appeal of the area is its early 20th-century Ottoman architecture. These buildings, in fact, were used by Kemal Mustafa Atatürk when he was commander of the Ottoman Second Army. And the Citadel was used by the Turkish military up until 2007, after which it was converted to a tourist attraction.

While I didn’t visit, there’s a small museum dedicated to Atatürk (one of many around Turkey) on the grounds as well.

Another noteworthy landmark of the Citadel is the Amida Höyük mound. Amazingly, pottery fragments from as far back as the 6th millennium BC have been found here.

The decayed building you see atop the mound today is the Artukid Palace, constructed in the early 13th century. The mound, however, was off-limits at the time of my visit due to ongoing archaeological excavations.

The Archaeology Museums

Past the ticket gate, the first large building on the left is the former Gendarmerie Barracks, constructed in the late 19th century. But it currently houses the Diyarbakır Archaeology Museum. One of two, in fact, as the building across the courtyard houses even an even larger collection.

The first museum provides an informative overview of Diyarbakır’s history, from the Neolithic era through Ottoman times. There’s a nice little collection of ancient stone tools and vessels, along with models of prehistoric settlements found throughout the province.

Additionally, there’s plenty of signage providing background info on the various landmarks you can find around the Old City.

The larger building on the opposite end of the Citadel focuses more on the Neolithic age through the Bronze Age. But some later artifacts are on display as well, including some damaged armor found right around the area.

Diyarbakır Province is home to several highly significant Neolithic settlements, such as Çayönü and Körtik Tepe. These sites date back to what archaeologists call the ‘Pre-Pottery Neolithic A’ period, ranging from around 12,000–10,800 years ago.

These sites, however, are overshadowed by the even older Göbekli Tepe in Şanlıurfa Province, and few tourists visit them. Nevertheless, this museum provides lots of detailed info on these significant sites, along with numerous later settlements.

Saint George Church

Also within the citadel is the Saint George Church which could be as old as the 4th century AD. But much of the surviving structure was later rebuilt by the Artukids. There’s no art or furniture to see inside, but it’s definitely worth a quick visit.

Wandering the Old City

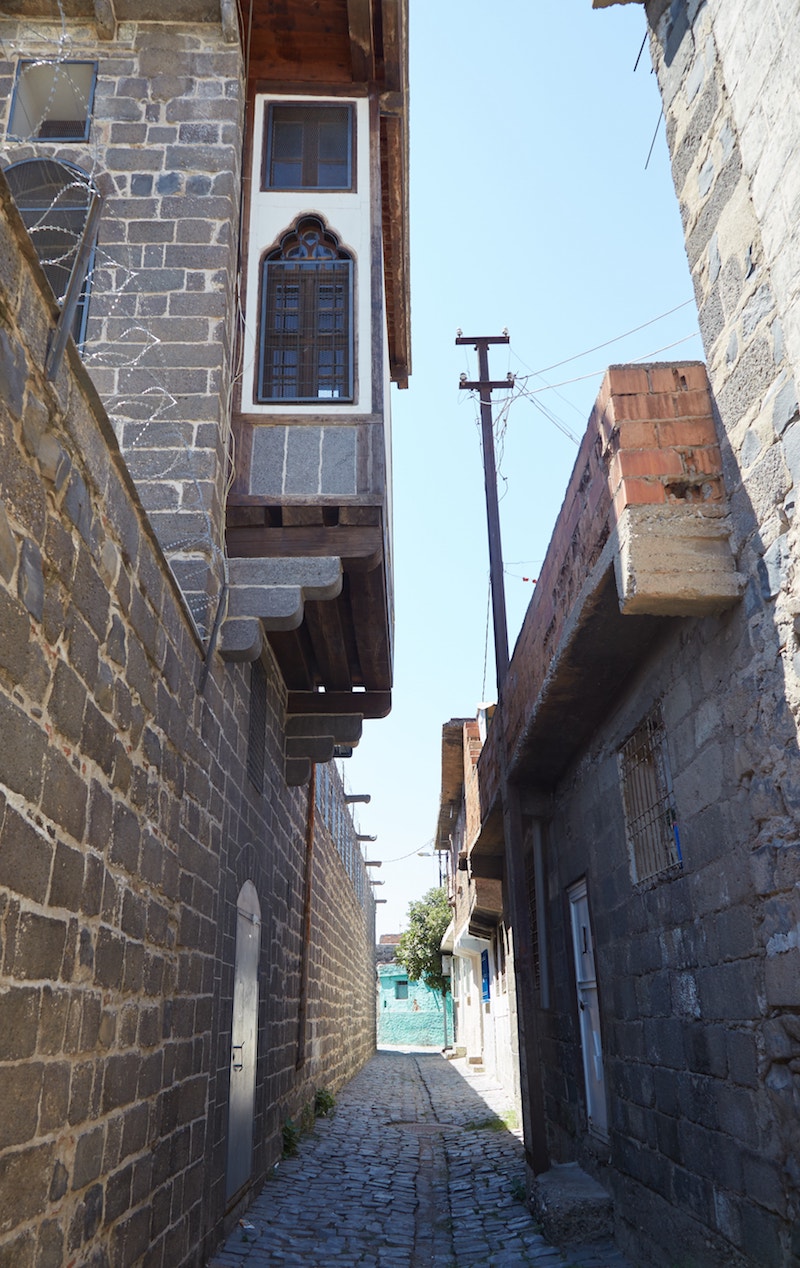

Most of the following locations in this Diyarbakır guide can be found by wandering the backstreets of the Old City. And these narrow alleyways are where you’ll discover the city’s real charm.

It’s not the easiest place to navigate, but getting lost and wandering around Diyarbakır’s maze-like streets is a big part of the experience. You’ll encounter local markets, tea shops, pleasant parks and all sorts of interesting buildings that don’t appear in guidebooks or maps.

One of the main things to check out while wandering Diyarbakır’s backstreets is Hasan Paşa Hanı, commonly featured in promotional posters. The 16th-century han, or caravanserai (traditional roadside inn), features a striped fountain in the center of a large courtyard.

It’s now full of various cafes, bookshops and restaurants spread across two stories. Traditional bazaars, meanwhile, can be found just nearby.

House Museums

Traditional Diyarbakır houses were typically built of basalt and contained open courtyards for relaxing. The city now has at least three museums where members of the public can go and see what they looked like.

Aside from the locations below, other traditional houses around the city have been converted into restaurants.

Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı Museum

The Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı Museum is the former house of the poet of the same name. The house, which was originally built in 1820, was purchased by the city government in 1973.

While most visitors coming from afar will have never heard of Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı, the elegant basalt house with its spacious courtyard is well worth a visit. Entry is free, while the courtyard also functions as a coffee shop.

Ziya Gökalp Museum

This museum is situated in the former house of Ziya Gökalp, an early 20th-century writer who helped develop the idea of Turkish nationalism.

Unlike the other museums, entry here costs 10 TL. While the traditional house itself is interesting, all of the information about the man and his life is in Turkish only.

Out of the three museums on this list, Ziya Gökalp’s is the least essential for foreign visitors.

Diyarbakır City Museum

The largest of the house museums is now known as the Diyarbakır City Museum, opened in 2010 after years of restoration. At the time of writing, entry to the museum is free.

The house belonged to a prominent Kurdish family, the last head of which was named Cemil Pasha. The family members were major supporters of Kurdish nationalism and were forcibly exiled from Diyarbakır in the early 20th century for their political involvement.

The courtyard here is massive. And much like traditional royal palaces, there were entire separate sections designated for women and men. Other wings once contained the former kitchen and baths.

As the current name suggests, this is now a museum dedicated to the history and culture of Diyarbakır, but none of the information is in English. There are, at least, historical photographs of the city from the early 20th century. Also on display are interesting antique artifacts, many of which belonged to Cemil Pasha’s family.

At the museum, you’ll find numerous pictures of the Shahmaran, a Kurdish mythical creature. In fact, depictions of this half-woman, half-snake being are common all throughout southeastern Turkey.

According to legend, she lived in a cave and fell in love with a young man named Camasb who stayed there with her. But eventually, he decided to return to the world and promised the Shahmaran not to reveal her whereabouts.

But when it was discovered that the sick king could only be cured by consuming her flesh, Camasb broke his promise. The Shahmaran was killed and her flesh saved the ailing king, while Camasb ended up becoming a famous physician.

Ulu Cami (Grand Mosque)

Diyarbakır became a Muslim city as early as 639. And upon conquering the city, the Muslim invaders converted the existing Cathedral of St. Thomas into the city’s main mosque. That makes Diyarbakır’s Ulu Cami one of the oldest mosques in all of Anatolia.

The mosque we see today, however, was largely rebuilt by the Seljuk Turks in the 1090s. Ulu Cami’s current form is largely modeled on the 8th-century Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria – itself built over an existing church.

And after the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, Ulu Cami is considered to be the fifth holiest site in Islam.

Most of the mosque’s highlights can be viewed from within its large courtyard. Its tall minaret was built of brick in the typical Diyarbakır square-shaped style. Its top, however, was later added by the Ottomans.

The center of the courtyard contains two large conical ablution fountains, while you’ll also notice a small sundial. It was designed by 13th-century engineer Al Jazari, who wrote numerous scientific books while living in Diyarbakır. And he’d go on to become one of the most respected engineers of the Islamic world.

The courtyard’s four sides, meanwhile, represent the four different schools of Sunni Islam: Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i and Hanbali. Most Muslims in Anatolia are followers of the Hanafi school.

Walking around the courtyard, you’ll notice the Corinthian columns and other motifs common in Greco-Roman architecture. The builders weren’t merely inspired by this art, but usurped the pieces from a nearby ancient amphitheater.

Looking closely, you’ll also notice Arabic calligraphy that was later carved into the stone. This clash of styles is what makes Diyarbakır’s Ulu Cami one of the most unique mosques in all of Turkey.

Other Mosques & Churches

There are many more mosques and churches to see around Diyarbakır, and this is by no means an exhaustive list. Diyarbakır, in fact, has so many ancient structures that some even consider it to be on par with Istanbul in terms of historic architecture.

The Four-Legged Minaret

One of Diyarbakır’s most unique landmarks is its ‘Four-Legged Minaret,’ known locally as Dört Ayaklı Minare. It’s the only minaret in all of Turkey to stand on four legs, and the 16th-century construction has since become a symbol of the city.

At two meters off the ground, the basalt pillars are tall enough to walk under, which some locals do for good luck. The legs are believed to represent the four different schools of Islam.

Constructed during White Sheep Turcoman rule, the minaret belongs to the Shaikh Mutahhar Mosque, otherwise built in the typical style of the city.

Safa Mosque

The Safa Mosque is most know for its minaret, which is entirely covered in intricate floral designs. The design is quite similar to what you’ll find in nearby Mardin.

The mosque was commissioned in 1532 by the sultan of the Akkoyunlu, or White Sheep Turcomans. Supposedly, various aromatic herbs were used in the mosque’s construction, giving it the nickname ‘the scented mosque’!

The interior, meanwhile, is known for its Persian-influenced blue ceramic tiles.

Behram Pasha Mosque

Constructed in the 1560s, Behram Pasha Mosque was named after the governor of Diyarbakır at the time. To this day, it remains the second-largest mosque in the city.

It was designed by none other than Mimar Sinan, the chief architect of the Ottoman Empire. He was the man behind such masterpieces as Istanbul’s Süleymaniye Mosque and Edirne’s Selimiye Mosque.

But you would never guess, considering how similar this building looks to Diyarbakır’s other mosques. It just goes to show the sensibility of Sinan, who designed buildings with their surroundings in mind.

Mimar Sinan was also behind the Iskender Pasha Mosque, which is currently in use as an outdoor restaurant.

Yet another of Sinan’s creations is the Melek Ahmet Pasha Mosque, though the marker on Google Maps was incorrect and I could never find it. (Perhaps it’s in the off-limits section of the city.)

Nebi Mosque

Built in 1530, Nebi Mosque, or the ‘Prophet’s Mosque’ features alternating black and white stripes of stone. The design, as you’ve surely noticed, is common all throughout Diyarbakır. It supposedly represents the White Sheep and Black Sheep Turcoman tribes which controlled much of eastern Anatolia around this time.

Interestingly, the interior domes were clearly influenced by Ottoman-style mosques.

Various sections of the mosque feature lines from the Hadith, or holy book of Muhammad’s sayings.

Ali Pasha Mosque

Located in the southwest portion of the Old City, the Ali Pasha Mosque dates back to the 16th century and was named after an Ottoman governor.

In addition to a mosque, the complex also contains a madrasa (school) and bath. While impressive on its own, there’s little to make it stand out from all the other mosques in Diyarbakır.

Syriac Virgin Mary Church

Throughout its history, Diyarbakır was home to a sizable Christian population comprised of various sects. While the Christian community today is tiny compared to past numbers, a few active churches can still be found in the city.

One of them is the Syriac Orthodox Virgin Mary Church, known locally as Meryem Ana Kilise. It’s known for its open courtyard and ancient frescoes. The site was also home to a pagan sun temple thousands of years prior.

During my visit, the church was closed for reasons related to the coronavirus pandemic. I was, however, able to visit a couple of Syriac Orthodox churches in nearby Mardin and Midyat.

Armenian Catholic Church

The Armenian Catholic Church has long been abandoned. Ironically, for that reason, it was the only church I was able to access during my time in Diyarbakır.

Most Armenians are Orthodox Christians with their own national church, the Armenian Apostolic Church. But as evidenced here, there’s long been a sizable Armenian Catholic community as well.

While the roof of the church has completely vanished, the structure’s multiple arches remain perfectly intact. It makes for an interesting visual spectacle quite unlike anything else in the city.

There are multiple rooms to explore, and you can even walk up a staircase to view the ruins from the second story.

Completely abandoned and forgotten, this 16th-century basalt structure is one of Diyarbakır’s most intriguing, and should not be missed. It’s unclear though, how long city officials are going to allow it to last.

The more famous Armenian church of Diyarbakır, Surp Giragos, was completely off-limits during my visit due to massive construction taking place in that area. When it was open, it was situated in the backyard of an ordinary resident’s house!

The City Walls

Encompassing the city at a total length of 5.7 km, Diyarbakır’s city walls are considered to be the world’s longest after the Great Wall of China! The original walls were built by the Romans after they took the city from the Persian Sassanids.

The various Islamic kingdoms to later control the city then repeatedly repaired and expanded them. In the 11th century, the Seljuks added four bastions, while the Artukids added two more in 1208.

The walls have four main gates – Dag to the north, Mardin to the south, Urfa to the west and Yeni to the east.

One of the main activities for tourists visiting Diyarbakır is walking atop the walls. However, the current situation seems a bit different from what I’d read about online and in guidebooks.

While it was supposedly once possible to walk across much of the city this way, this is no longer the case. There are various obstacles blocking the path at some parts, presumably placed for safety reasons.

Additionally, the dark passageways leading to the top are best avoided. While Diyarbakır is generally safe, these empty towers are where the local junkies hang out and where some shady business transactions go down. They also reek.

Though I’d read that there was an easy way up near the western Urfa Gate, I didn’t see one around there. Continuing south, I eventually did find an outer staircase not far from Ali Pasha Mosque.

From this point, I was able to successfully walk all the way to the Mardin Gate, though I had to backtrack a bit at the end to find a staircase down.

If you’re taking this route, you’ll pass through the Yedi Kardeş, or Seven Brother’s tower on the way over. And as you eventually get closer to the Mardin Gate, you’ll pass through an interesting little tunnel before you reach the end.

The top of the walls have no protective barriers of any kind, so those with bad balance or a fear of heights may want to sit this one out.

If you’re not up for a walk atop the walls, you can still walk just inside or outside of them for much of their length. There are well-kempt grassy parks on either side of the walls where locals like to gather and hang out.

If you’re visiting in summer, you’ll also encounter entrepreneurial young boys hawking bottles of water for one or two liras.

Keçi Burcu

Another popular walk you should try is just outside the city’s eastern walls. Beginning at Keçi Burcu, translating to ‘goat tower’ for obvious reasons, there’s a pedestrian-only road leading all the way to the Citadel.

There are even some cafes on the side of the path, along with various lookout points to take in the views of the Mesopotamian plains.

The lush green area is officially known as the Hevsel Gardens. Consisting of seven hectares of land on either side of the Tigris River, the area is now recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Hevsel Gardens have long provided nourishment for Diyarbakır residents, from ancient times until today.

Walking to Dicle Bridge

For an even closer look at the Tigris River, consider a scenic walk to the Dicle Bridge, about 3 km south of the Old City.

As you make your way past the ancient fortification, don’t forget to turn around to take in the walls from afar. Interestingly, residents only started building outside the walls quite recently. For millennia, most Diyarbakır residents only ever considered living within them.

The walk to the bridge is scenic and quiet, and on the way there you can stop at a traditional house called the Gazi Paşa Kösk. The house was originally built in the 15th century as a villa for the White Sheep Turcomans. In modern times, however, it’s largely associated with Atatürk, simply because he once stayed there.

There’s a spacious park in front where local families regularly gather for picnics. And you’ll also find plenty of Turkeys wandering around! Or more precisely, guineafowels.

It turns out that there actually is a connection between Turkey the country and the North American bird. Supposedly, the British named the American birds Turkeys because of their resemblance to the guineafowels that they’d been buying from the Turks.

Returning to the main road and continuing south, the Dicle, or Ten Eyed Bridge will soon come into view. The bridge, constructed by the Seljuks in 1065, stretches out to 178 m long. And it also features ten arches from which it takes its name.

There’s not a whole lot to see other than the bridge itself. You can, however, walk across and sit down at one of the numerous riverside cafes.

A trip to the bridge makes for a pleasant extra excursion if you’re into walking and the weather is nice. Otherwise, if you’re short on time, focus on the attractions within the city walls mentioned in the Diyarbakır guide above.

Additional Info

Diyarbakır has its own airport with direct flights to cities like Istanbul and Ankara. It might be a good place to start for those wanting to explore the southeast but don’t have time for Van.

Diyarbakir is just a couple-hour bus ride from Mardin. Understand, however, that this is a dolmuş, or minibus, and not a coach bus. To catch minibuses to and from nearby cities like Mardin, you’ll need to use the regional bus terminal, or Ilçe Otogar. This is located to the southwest of town in a completely different place from the main otogar (see map above).

Coach buses from more distant cities will arrive at the main otogar, inconveniently located 14 km away from the city center. As of 2020, a taxi to the Old City should cost around 35 TL.

I took a bus from Van with the Metro Bus Company, which lasted about 6 hours. At Van, they offered a free shuttle service from the city center to the Van otogar. But arriving in Diyarbakır, no such service was available.

Diyarbakır also has a railway station, though few foreign visitors are likely to travel this way. You will have to come via cities like Ankara or Kayseri, and they may not leave every day.

With so many bus companies connecting to Diyarbakır, including the city’s own Öz Diyarbakır company, a bus of some sort will be your best option.

I stayed at a hotel called Koprucu Hotel situated just next to Nebi Mosque. It’s right outside the northern walls of the Old City and it was easy to get everywhere in the above Diyarbakır guide on foot.

The rooms featured a private bathroom, air conditioning and breakfast for a reasonable price. The staff didn’t speak a word of English, but we communicated via translation apps and they were quite helpful and kind.

As long as you stay somewhere within or just outside the Old City walls, you’ll be fine.

Diyarbakır has long had a bad reputation. But had I been unaware of this coming in, I never would’ve imagined this to be the case during my visit.

Since the major fighting between Turkish government forces and PKK rebels in 2016, the security situation has largely been stable. The part of the Old City that was destroyed during that time was still being rebuilt as of 2020 and was completely closed off during my visit.

But as you can see from the Diyarbakır guide above, most of the significant landmarks have survived.

Even now, numerous government agencies advise against travel to this region. You will have to do your own research and use your own judgment, but I can honestly say that in 2020, I never felt unsafe while traveling in southeast Turkey. And I spent nearly a month in this region alone.

I’ve also read reports about street safety in Diyarbakır, but again, my experiences were different. There were, as mentioned, some unsavory characters in the darkened city wall staircases. But they can easily be avoided and I only had positive interactions with the locals.

While you still want to be sensible and stay away from places or people that just don’t feel right, don’t let the city’s reputation dissuade you from visiting. To me, Diyarbakır felt as safe as any other city in Turkey.

While the Turkish government isn’t quite as extreme as China when it comes to online censorship, you’ll probably want a decent VPN before your visit.

I’ve tried out a couple of different companies and have found ExpressVPN to be the most reliable.

Booking.com is currently banned in the country (at least when you search for domestic accommodation). However, there are actually quite a few Turkish hotels listed on there anyway. And many them don’t even appear on Hotels.com, which hasn’t been banned.

Over the course of my trip, I ended up making quite a few reservations with Booking.com and was really glad I had a VPN to do so.

Another major site that’s banned is PayPal. If you want to access your account at all during your travels, a VPN is a must.

While those are the only two major sites that I noticed were banned during my trip, Turkey has even gone as far as banning Wikipedia and Twitter in the past.

Pin It!

Simply extraordinary Diyarbakir guide!! Much appreciated!

Thank you, have a good time there!