Last Updated on: 26th July 2022, 02:22 pm

The ancient Egyptians built over a hundred pyramids, with over 30 of them belonging to pharaohs. But most people only know just three. And while one would think that the iconic pyramids of Giza were built near the end of Egyptian civilization, in fact the opposite is true.

The rise of the Pyramid Age, which began in the 3rd Dynasty, was sudden and dramatic. And despite the technique being perfected in the 4th Dynasty, later pharaohs would never be able to match what their predecessors accomplished. But why?

We can only attempt to answer such questions by first going over the major Egyptian pyramids in chronological order. And after that, we’ll attempt to uncover some puzzling pyramid mysteries that have yet to be solved.

The following pyramid list is presented according to the official narrative preferred by Egyptologists. And we’ll mainly be focusing on the pyramids that one can go and visit as a tourist in Egypt.

If you’re looking for a complete list of all the Egyptian pyramids, check below for some recommended reading.

3rd Dynasty Pyramids

It was Egypt’s 3rd Dynasty, which began around 2868 BC, that gave birth to the country’s Pyramid Age. While Djoser’s Step Pyramid, the world’s very first, still looks fantastic today, Djoser’s immediate successors wouldn’t have quite as much success.

The Step Pyramid of Djoser

Mastabas were a traditional form of Egyptian tomb built as stone rectangular structures. But King Djoser and his architect Imhotep decided to see what would happen if they stacked multiple limestone mastabas on top of one another.

After the base was initially constructed, Imhotep decided to expand it and add three additional smaller layers on top, resulting in a four-stepped pyramid.

And later, the base was enlarged yet again. Two additional levels were added to the top, resulting in its final 6-tier form. Archaeologists believe that as many as five changes of plan took place during construction!

The pyramid has a base of 121 x 109 meters and stands at 60 meters high. Remarkably, despite being the very first attempt, few subsequent pharaohs from the 5th Dynasty onward would be able to surpass it in height.

Outside, the pyramid features a large court for the royal Heb-Sed festival along with an extensive temple complex. Beneath the pyramid, meanwhile, King Djoser was buried within an elaborate underground labyrinth meant to mimic his royal palace.

The Step Pyramid’s underground tunnel system is arguably as impressive as the pyramid itself. And uniquely, portions of the halls were decorated with blue tiles – a feature that no later pharaoh would copy.

We also see reliefs of the king in motion, while the centerpiece is a 4.7-high rectangle comprised of 32 granite blocks. Situated directly beneath a long shaft dug deep into the earth, it’s here that the king’s body was originally laid to rest.

The Step Pyramid of Djoser isn’t only the first pyramid, but it’s also among Egypt’s most impressive and unique.

LEARN MORE HERE

The Pyramid of Sekhemkhet

Egypt’s second-ever pyramid didn’t turn out nearly as well as the first attempt. Built for Djoser’s successor Sekhemkhet around 2645 BC, it has the unfortunate nickname of the ‘Buried Pyramid.’

Located several hundred meters southwest of the Step Pyramid, it was clearly modeled after the original. But as was common in Egypt, projects such as tombs and pyramids would typically be halted when the main benefactor died.

As Sekhemkhet only ruled for around 6 years, his pyramid never got off the ground – literally. But you can still find the foundations in Saqqara by walking south into the desert from the Pyramid of Unas.

LEARN MORE HERE

Various Territorial Pyramids

Huni, the last king of the 3rd Dynasty, built several small pyramids at places such as Aswan’s Elephantine Island, Edfu and Abydos. But these were clearly not tombs.

For example, the Elephantine Island pyramid’s base is 18.46 meters long. And in its current ruined state, it’s only about 5 meters high. The other small step pyramids built throughout the country share similar dimensions.

The true purpose of these small pyramids remains a mystery. Perhaps they were built at holy places related to Egyptian mythology. Or maybe they were political, meant to demarcate Egypt’s provinces, or nomes.

Some of these small step pyramids may have also been built by Sneferu (see below), but scholars aren’t entirely sure.

4th Dynasty Pyramids

Mention Egyptian pyramids to anyone and they’re going to picture the pyramids of Giza created by Egypt’s 4th Dynasty (c. 2613-2494 BC). In fact, the 4th Dynasty pyramids are so famous that many are unaware that others exist!

But before Giza was even established, the dynasty began with arguably the greatest pyramid builder of them all – Sneferu.

Meidum

The pyramid is generally attributed to Pharaoh Sneferu, the king behind the two main pyramids at Dahshur (see below). But it’s completely unique among Egyptian pyramids for having been built in two distinct phases.

The builders at Meidum first constructed a tall, steep core. They then added several narrow layers, or bands, of masonry around it, all leaning inward against the core. This construction style was reminiscent of constructions started by Huni, so it’s possible that the first phase was built at the end of the 3rd Dynasty.

But at some point, someone (likely Sneferu) returned to build a smooth-sided pyramid around it. This pyramid even had an angle of 51°52′ – the same as the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Obviously, it eventually collapsed, bringing much of the first construction phase down with it. While nobody’s really sure, it may have survived intact for over a thousand years, well into the New Kingdom period or later.

Most Egyptologists believe that Sneferu built the step pyramid at Meidum before going on to build the Bent and Red Pyramids. Then, after mastering the craft, he returned to Meidum to give it a major makeover. But this is all just conjecture.

There’s not much hard evidence linking Sneferu with the pyramid at Meidum, though some of his relatives were buried in mastabas nearby.

In contrast with Djoser’s Step Pyramid, the burial chamber at Meidum was built into the pyramid and not beneath it. Past the entrance chamber, a 6.25-high vertical shaft protects the main burial chamber.

The central chamber has a corbelled roof, an architectural feature found at all later 4th Dynasty Pyramids, but no others.

Incredibly, Sneferu is credited with three pyramids in total. But if all pyramids were supposedly tombs, why did he need so many? Egyptologists like Mark Lehner believe that Meidum functioned not as a tomb but as a cenotaph.

Unlike Djoser’s Step Pyramid, the interior lacks any carvings or decoration whatsoever. This is another trend that would persist throughout the 4th Dynasty.

LEARN MORE HERE

The Bent Pyramid

In Dahshur, roughly 10 km south of Saqqara, Sneferu would go on to build two more pyramids, both of which remain in impeccable condition today.

While there’s no hard evidence regarding which order he built them in, Egyptologists believe that the Bent Pyramid was first – mainly because they also deem it to be a mistake.

According to the official narrative, the Bent Pyramid was meant to be a smooth-sided pyramid. But some pesky structural issues called for a change of plan midway.

The bottom half of the pyramid is inclined at 53°27′, but around midway up, the angle suddenly changes to 43°. What also makes the pyramid unique is that it has two entrance tunnels and two ‘burial chambers,’ albeit with no evidence of a burial.

Despite Egyptologists considering it flawed, it’s rather ironic that the Bent Pyramid is one of the best-preserved pyramids in Egypt. Even many of its limestone casing stones remain intact.

On the south side of the Bent Pyramid is a smaller satellite pyramid. Mark Lehner suggests that this was the first-ever Egyptian pyramid built by altering courses horizontally rather than vertically.

He also believes that the method of casing stones used here would go on to influence the method later used at Giza.

Curiously, the internal chamber is much too small for a burial.

The Red Pyramid

Some 2 km north across the desert, Sneferu would also build the Red Pyramid, named after the reddish hue of its limestone.

Egyptologists believe that Sneferu, after two botched attempts (Meidum and the Bent Pyramid), finally succeeded here at making the world’s first ‘true’ pyramid. It was built at a slope of 43°22′.

The Red Pyramid’s granite-lined inner chamber is accessible via an entrance along its north face. The tunnel is set at a steep slope and stretches out to over 60 m long.

Visitors will first encounter an antechamber with a corbelled roof. And then, a short passageway then leads to yet another antechamber with a corbelled roof. The entrance to the main burial chamber is several meters off the ground, now accessible via modern wooden steps.

The central burial chamber also has a corbelled roof. But looking down, you’ll see a pile of rough stones which contrasts the smooth masonry above.

Lehner believes the Sneferu would’ve chosen the Red Pyramid as his tomb, though no evidence of a burial exists.

If Sneferu really is responsible for all these pyramids within his 24-year reign, it means that he oversaw the quarrying and transport of roughly 9 million tons of stone. That’s over three times the amount of stone in the Great Pyramid, and equivalent to around one million truckloads!

LEARN MORE HERE

The Great Pyramid of Khufu

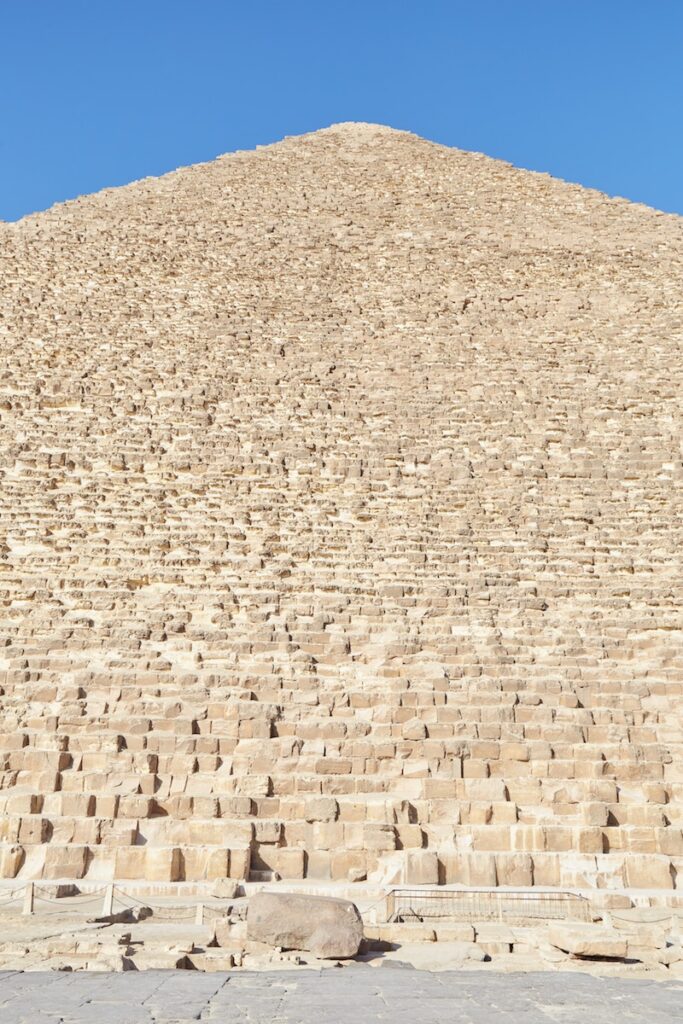

Khufu, Sneferu’s son, is credited with what’s dubbed the ‘Great Pyramid.’ And for good reason. It’s the largest pyramid ever built and it’s arguably the most famous landmark of the ancient world.

Rather than build at Dahshur, Khufu established a new site at Giza, some 24 km north of Saqqara.

The Great Pyramid stands at 147 meters high and is comprised of 2.3 million limestone blocks, each weighing around 2.5 tons. But like the Red Pyramid, the inner chambers are comprised of granite.

It originally would’ve appeared white, though most of its limestone casing stones have been plundered over time.

Egyptologists believe that construction was entirely carried out within Khufu’s reign, which may have been as short as 24 years (2589–2566 BC). And to this day, nobody can explain how it was built. The topic has been the subject of much debate and controversy for centuries.

The Great Pyramid is labeled as a tomb (and nothing more) by Egyptologists. But one of its most remarkable and mysterious features is that its dimensions accurately represent the Northern Hemisphere at a scale of 1:43,200!

The highlight of the interior is the Grand Gallery, a walkway that’s 48 m long and gradually rises up around 8.5 m. It has a corbelled roof and a series of 14 mysterious notches on its sides.

Like the Bent Pyramid before it, the Great Pyramid has two burial chambers. The King’s Chamber contains a granite sarcophagus, though no traces of a lid (or burial) have ever been found.

In contrast to the typical tombs of the time, the pyramid is entirely undecorated.

Just outside the Great Pyramid are a series of three small pyramids known as the ‘Queens Pyramids,’ attributed to Khufu’s wives.

In the northernmost one, belonging to Queen Hetepheres, the sarcophagus and personal artifacts of the queen were discovered. While her body was missing, her organs were there in canopic jars.

A king named Djedefere directly succeeded Khufu. But he built at nearby Abu Rowash instead of at Giza. His pyramid is off-limits to most visitors but can be visited as part of special group tours.

The pyramid has a deep burial chamber going down into the earth. Strangely, its architecture more closely resembles some unfinished pyramid projects of the 3rd Dynasty than those of Djedefere’s father and grandfather.

It was possibly once completed, but most of its stone has been plundered and not much remains.

The Pyramid of Khafre

Pharaoh Khafre, who reigned from 2520-2494 BC, is credited with Giza’s central and second-largest pyramid. At 136 meters, the pyramid is just 3 meters shorter than the Great Pyramid. However, it looks even taller, having been built on a higher plateau.

The pyramid is angled at 53°10′, forming a perfect 3:4:5 triangle. And it sits within an enclosure entirely dug out of the bedrock.

What’s unique about the pyramid is that many of the casing stones at the top remain in place. And on the pyramid’s south side you’ll find the ruins of Khafre’s mortuary temple.

References to Khafre have been found at this funerary complex, while Herodotus also credits Khafre with this pyramid. But otherwise, the pyramid is largely anonymous.

The pyramid has two entrances (both original), with one having been placed directly above the other.

The main inner chamber is lined with limestone and sits under a gabled roof. Unlike the sarcophagus of the Great Pyramid, this one is largely undamaged and it even has its lid intact.

But no body or any trace of a burial was ever found inside.

LEARN MORE HERE

The Pyramid of Menkaure

The third pyramid of Giza is that of Menkaure, Khafre’s son, who ruled from 2490-2472 BC. It’s just half as high as the other two Giza pyramids. The real reason for this sudden decrease in size remains a mystery. But one possibility is that there wasn’t enough space.

All three Giza pyramids are aligned so that their southeastern corners form a diagonal line pointing straight to the Sun Temple of Heliopolis. So in order to maintain the alignment, Menkaure couldn’t just build anywhere he pleased. Quite possibly, the geography of the area with which he was stuck didn’t allow for a structure as grand as the others.

But as we’ll see below, no pyramid anywhere would ever come close to matching those of Khufu or Khafre.

Uniquely, the bottom of its exterior is entirely lined with red granite casing stones, while the now bare upper half was once dressed in limestone. What’s especially peculiar is that some parts of the granite have been smoothed down while other sections remain rough.

If we are to judge a dynasty by its construction projects, the 4th Dynasty – the greatest of them all – certainly came to a strange and anticlimactic end. The last pharaoh of the dynasty, Shepseskaf, didn’t even build a pyramid at all.

Instead, he built a simple but sizable mastaba, known as Mastabat Fara’un, in the southern portion of Saqqara (currently inaccessible).

But it’s not the only mysterious construction built at the end of the 4th Dynasty. Not many realize that Giza actually has a fourth pyramid which belonged to woman named Khentkaus I.

While uncertain, she may have been Menkaure’s daughter or Shepseskaf’s wife. And some think she may have even briefly ruled as pharaoh.

Her pyramid was built over a large limestone outcrop. And just like the other pyramids, it even features a Mortuary and Valley Temple.

5th Dynasty Pyramids

The 5th Dynasty pharaohs (c. 2465-2323 BC) remained as enthusiastic about pyramids as ever. But while they implemented some new innovations like the Pyramid Texts inscriptions, their constructions could never compare with those of their recent predecessors.

The Pyramid of Userkaf

Userkaf was likely one of Menkaure’s sons. But Manetho (a Ptolemaic-era priest/historian who first divided up the Egyptian dynasties) credited him with founding the 5th Dynasty.

Userkaf was the first pharaoh to build a (finished) pyramid at Saqqara since the reign of King Djoser. His pyramid is currently closed but can be seen from the outside as you tour Saqqara.

In tremendous contrast to the 4th Dynasty pyramids, Userkaf’s consisted of a rubble core only held together by its outer limestone casing. But once the casing was stripped, the whole thing fell apart. And the pyramid was only 49-meters high before its collapse.

Compared with the massive pyramids of Giza, it almost looks like something built by a different civilization. As mentioned, Userkaf was likely Menkaure’s son. So what caused such a sudden decline in pyramid building techniques in such a short amount of time?

Some scholars believe that since the 5th Dynasty was so focused on building Sun Temples, they lacked the resources to build large pyramids. But the temples of Giza seemed to have used a much greater amount of stone than the temples of the 5th Dynasty.

The Pyramid of Sahure

The next several rulers of the 5th Dynasty built at a new site called Abu Sir, situated in between Giza and Saqqara. Userkaf had previously built a Sun Temple in the area, but Pharaoh Sahure was the first to build a pyramid.

Though largely in ruins today, Sahure’s pyramid had a long causeway leading up to it and an elaborate Mortuary Temple out front.

Instead of rubble, the pyramid consists of limestone blocks, though they’re significantly smaller than what was used at Giza. With the outer casing gone, we can see that the pyramid’s core is a five-tiered step pyramid held together with mud mortar.

The pyramid’s entrance is on its north side. While inaccessible today, the interior consists of a straight entrance tunnel leading directly to the burial chamber in the structure’s center. The chamber was lined with massive limestone blocks, with some weighing as much as 275 tons!

LEARN MORE HERE

The Pyramid of Neferirkare

Neferirkare, Sahure’s immediate successor, ruled for 20 years, from around 2446-2426 BC. And his pyramid is the largest at Abu Sir. It originally stood at 70 meters high, making it slightly taller than Menkaure’s pyramid at Giza (65 meters). But today the ruined pyramid only stands at around 52 meters.

The exposed core reveals a six-tiered step pyramid – one higher than that of Sahure’s. It bears a striking resemblance to Djoser’s Step Pyramid which is visible across the desert. But the builders eventually filled it in to make it a ‘true’ pyramid.

The Pyramid of Raneferef

The Pyramid of Raneferef was situated southwest of Neferirkare’s pyramid. While likely never finished, its northwest corner aligns with Neferirkare and Sahure’s pyramids to point straight at Heliopolis.

Parts of its base can still be made out today.

The Pyramid of Nyussere

The next pyramid built at Abu Sir was that of Nyussere. And it appears much like the others. While not aligned to Heliopolis, it forms a straight line with Nyussere’s Sun Temple of Abu Gorab, about a 15-minute walk north across the desert.

The Pyramid of Unas

It wasn’t until the reign of the last 5th Dynasty king, Unas, that pyramid building would return to Saqqara (though the two prior rulers had unfinished projects there).

While the Pyramid of Unas is in much better shape than Userkaf’s, it still looks puny when viewed side by side with Djoser’s Step Pyramid.

In comparison with the relatively shoddy masonry of the core, the remaining casing stones appear nearly as tight and precise as those at Giza.

An inscription on the southern end of the pyramid mentions reconstruction efforts carried out during the reign of Ramesses II, over 1,000 years after the pyramid was built.

Unas implemented a brand new innovation in his pyramid – one that would set the course for pharaonic tombs for the remainder of Egyptian civilization. It’s here that the Pyramid Texts appeared for the very first time.

The Pyramid Texts, which deal with the resurrection of the king, are the world’s oldest religious texts. We can presume that they were even older than the 5th Dynasty, but hadn’t been inscribed in stone until this point.

Aside from the texts, the large granite sarcophagus in the burial chamber is also noteworthy. It appears to be as perfectly crafted as those inside the Giza pyramids. Yet it feels strangely oversized.

6th Dynasty Pyramids

The 6th Dynasty pharaohs (6th Dynasty (c. 2323-2150 BC) continued building pyramids in the style of the 5th. But at the time of writing, the Pyramid of Teti in Saqqara is the only 6th Dynasty pyramid that’s open to the public.

The Pyramid of Teti

Teti was the first pharaoh of the 6th dynasty, taking the throne just after Unas, the 5th Dynasty’s last ruler. His pyramid also contains the Pyramid Texts.

Like the Unas Pyramid, the entire wall is inscribed in hieroglyphs, and the overall size and layout is strikingly similar. Only the colors of the interior are different.

A vast mortuary complex surrounds Teti’s pyramid. In addition to numerous mastabas of royals, a few pyramids belonging to Teti’s queens remain standing as well.

The most notable construction is the pyramid of Queen Sesheshet, Teti’s mother. Its shape is rather unique and it appears more like some kind of stepped mastaba rather than a pyramid. Looking inside (from a distance), you can see an intact sarcophagus.

South Saqqara Pyramids

Several other 6th Dynasty pharaohs, such as Pepi I, Merenre I and Pepi II would also build pyramids at Saqqara. But these are in the southern part of the necropolis in an area currently off-limits to visitors.

You can catch a glimpse of them from the New Kingdom tomb area, but it’s difficult to tell which is which. According to experts who’ve studied them, they’re largely similar to the other 5th and 6th Dynasty pyramids, and they also contain the Pyramid Texts within.

The end of the 6th Dynasty marked the end of Egypt’s Old Kingdom era. And what followed was the First Intermediate Period, a chaotic time when local governors took prominence over the central government. As one might expect, such an unstable period leaves us with no pyramids.

Egypt would eventually be reunified by the 11th Dynasty, giving birth to a new era known as the Middle Kingdom. The 11th Dynasty produced no pyramids, but the 12th Dynasty would revive the tradition of their ancestors.

12th Dynasty Pyramids

The 12th Dynasty (c. 1991-1783 BC) produced some interesting yet largely overlooked pyramids. Many of them were comprised of mudbrick, and unsurprisingly, don’t hold up very well today. But where the 12th Dynasty pharaohs really excelled was with their burial chambers.

The Pyramid of Amenemhat I

Though the 11th Dynasty was based at Luxor, the 12th Dynasty pharaohs moved their capital to the area of the Fayoum Oasis. And the first two pyramids to be built in the Middle Kingdom were built in a place we now call Al Lisht.

While neither are open tourist attractions, you can see them from the outside if you hire private transport.

The first belongs to Amenemhet I, the 12th Dynasty’s founder. It was comprised of a composite of materials, including limestone blocks, mudbrick and even loose sand.

Interestingly, none of the Middle Kingdom pyramids seem to follow the building plans of anything built in the Old Kingdom.

Be that as it may, blocks from Khufu and Khafre’s pyramid complexes were usurped for parts of the descending passage. And as we’ll cover shortly, later 12th Dynasty pharaohs were major admirers of Sneferu.

The Pyramid of Senusret I

The other Al Lisht pyramid was built by Amenemhat I’s successor, Senusret I. It’s visible from Amenemhat’s, and looks more or less the same in its current state.

Senusret I, however, innovated a new pyramid building technique. He first built a series of stone walls within a square. The middle ones crossed to form an X, and the walls’ height increased near the center – sort of like a tent.

Additional smaller walls were built in the opening spaces, and then the gaps were filled in with stone and sand.

The White Pyramid

Senesret I’s successor, Amenemhat II, would go on to build the White Pyramid at Dahshur. This was the first of several efforts by 12th Dynasty pharaohs to build nearby Sneferu’s constructions.

Sadly for Amenmhat II, his pyramid, mostly built of limestone, is in such bad shape that it hardly resembles a pyramid at all. This is likely due to incessant quarrying over the centuries.

Uniquely, a long rectangular enclosure wall was built around it, not unlike Djoser’s.

Though numerous tombs were discovered nearby, extensive excavations have yet to be carried out.

The Pyramid of Senusret II

The next 12th Dynasty pharaoh, Senusret II, who took the throne around 1878 BC, returned to the Fayoum Oasis area. But instead of Al Lisht, he built his pyramid at a place called El Lahun.

Like his predecessors, Senusret II tried experimenting with a brand new construction style.

Senusret built almost the entire pyramid core out of just mudbrick. And he built much of it on top an already existing limestone outcrop – a bit like the Pyramid of Khentkaus. He also implemented some larger limestone blocks at the base for added stability.

Aside from its mudbrick construction, Senusret II broke with tradition in another way. He built the entrance to his chamber on the pyramid’s south side instead of the north. (The pharaohs believed their soul, or ba, exited the pyramid from the north.)

The underground chamber was built completely under the pyramid and not within it – quite like Djoser’s Step Pyramid.

But like the chambers of the Old Kingdom pyramids, Senusret II’s was made entirely from granite. Uniquely, however, this one has an arched ceiling. And the granite sarcophagus has a peculiar overhanging lid. To the naked eye, its corners appear just as straight and precise as those at Giza.

LEARN MORE HERE

The Pyramid of Senusret III

The next pharaoh, Senusret III, followed in his father’s footsteps and built another mudbrick pyramid encased in limestone.

But instead of at the Fayoum, he returned to Dahshur. Today it sits within a military base, but it can be seen in the distance from the entrance of the Red Pyramid.

Uniquely for the Middle Kingdom, this pyramid also had three small satellite pyramids on either side of it.

The Black Pyramid

The next pharaoh, Amenemhat III, is rare in Egyptian history for having built two pyramids. And this time he built at both Dahshur and the Fayoum.

The Dahshur pyramid, comprised of mudbrick, is nicknamed the Black Pyramid. Like the other Middle Kingdom pyramids in the area, it can only be seen from a distance.

Notably, despite the Black Pyramid’s ruined state, its pyramidion is the most complete royal pyramidion ever found.

Pyramidions functioned as a pyramid’s capstone, and they also represented the whole pyramid in miniature, utilizing the same angles and proportions of the original.

Hawara

Amenemhat III’s other pyramid was built at a place called Hawara, not far from El Lahun. Also built of mudbrick, it looks fairly similar to Senusret II’s pyramid.

Its chamber system, in contrast, was built right into the structure like most Old Kingdom pyramids. While entirely flooded today, the tunnels were built as a maze with all sorts of trapdoors and false walls meant to deceive potential thieves.

The burial chamber, meanwhile, was comprised of massive yellow quartzite monolith. And there were also were two sarcophagi discovered inside.

While separate from the pyramid structure itself, Hawara is much more well-known for what was built directly in front of it. The Hawara Labyrinth, as it’s called, was an incredibly vast and elaborate series of courtyards, palaces and shrines.

Sadly, it’s all been lost due to quarrying and looting. Some believe, however, that underground portions of it may still exist.

The 13th Dynasty & Beyond

The end of Amenemhat III’s reign marked the end of the 12th Dynasty, and arguably the end of the Pyramid Age. Some later kings, however, did embark on pyramid projects sporadically. But very little of them remains.

13th Dynasty pharaoh Ameny Qemau, who ruled in the 1790s BC, built a pyramid to the south of the Black Pyramid. It’s hardly discernible today, but its chamber was made of quartzite monoliths like those at Hawara.

Later, Pharaoh Khendjer built a mudbrick pyramid in South Saqqara. But it’s now totally ruined.

Like the First Intermediate Period, the Second Intermediate Period saw no pyramid construction. It was a time when Egypt was under foreign Hyksos rule until they were finally driven out by the 18th Dynasty.

And the first 18th Dynasty pharaoh, Ahmose, was the last native pharaoh to ever build a pyramid. Interestingly, he chose the ancient necropolis of Abydos for his project.

Its base was originally 52.5 x 40 meters. It was shoddily built of sand and rubble, all held together by limestone casing. But with the casing gone, it’s now just a 10 meter-high mound. Never intended as a tomb, it contained no burial chambers.

(Sadly, despite being less than 10 minutes down the road from Seti I’s Osiris temple, the security situation in the area prohibits tourists from going down that road to see it.)

From then on, the Egyptians, throughout the course of the illustrious New Kingdom area, would focus their attention on building elaborate temples instead of pyramids. The Pyramid Age was officially over.

Well, not quite. The Nubians in the Kingdom of Kush, just south of Egypt, built dozens of small pyramids made of sandstone and granite. And they didn’t even start the practice until the 8th century BC – around 700 years after the reign of Ahmose!

All of them, however, are situated in modern-day Sudan and not in Egypt.

During your travels around Luxor’s West Bank, don’t miss the workers’ tombs at Deir el-Medina. By then the New Kingdom pharaohs were being buried in rock-cut tombs, and the Der el-Medina workers were responsible for creating them.

Interestingly, while the pharaohs had long ceased building pyramids, the tomb builders themselves created miniature pyramids which marked the entrance to their own tombs!

Unanswered Pyramid Questions

According to our traditional understanding of history and human civilization, technology is supposed to get more advanced over time. But when examining the Egyptian pyramids, the opposite seems to hold true.

Below, we’ll be going over some of the most important mysteries regarding the pyramids that have yet to be solved.

Why Were the 4th Dynasty Pyramids so Superior?

As you can see from the chronological list above, and especially by visiting the pyramids in person, the 4th Dynasty pyramids are a major cut above the rest.

Not only the pyramids of Giza, but Sneferu’s Dahshur pyramids demonstrate a level of engineering far beyond what the later dynasties were capable of. As such, they also remain in the best condition today. It certainly flies in the face of our modern conceptions of progress and evolution!

But why was the 4th Dynasty – only the second dynasty to ever attempt building pyramids – so successful? And why couldn’t later dynasties follow suit? Egyptologists don’t seem to have an answer.

Some will argue that kings like Khufu were able to build the Great Pyramid because he was a ruthless, tyrannical leader. But history has seen countless tyrants rule nations across the globe. And none of them has ever built something on the level of the Great Pyramid.

And aside from old tales told to Herodotus thousands of years after his reign, there’s no evidence that Khufu was such a bad guy.

What Happened After the Reign of Menkaure?

As mentioned above, the 4th Dynasty ended rather strangely. Following the reign of Menkaure, the last pyramid builder at Giza, the next pharaoh wouldn’t even try building a pyramid at all.

The next normal pyramid built was that of Userkaf, which was both a small and terribly shoddy.

While there may have been some instability at the end of the 4th Dynasty, there doesn’t seem to have been a great political upheaval. The Old Kingdom era wouldn’t even start to unravel until the end of the 6th Dynasty.

So if Userkaf was a direct descendant of Menkaure and the earlier 4th Dynasty kings, how come he didn’t copy their construction techniques?

Maybe the political or economic situation didn’t allow for a pyramid as grand as those at Giza. But bizarrely, it seems as if all knowledge of pyramid building methods got wiped out in a single generation. And no later dynasty would ever be able to replicate the 4th Dynasty’s techniques.

Compare this to the non-royal tombs of the same time period. We see no major change in tomb art or construction styles from the 4th to 5th Dynasty. Pyramids aside, all other aspects of Egyptian civilization carried on seamlessly.

Could the 4th Dynasty

Pyramids be Older than Believed?

Many so-called ‘alternative researchers’ are adamant that the 4th Dynasty pyramids are much older than Dynastic Egypt. And even if you disagree, it’s not hard to see why many would think this.

According to the Egyptians themselves, semi-divine beings ruled the country for tens of thousands of years before the reign of the ‘first’ pharaoh, Narmer.

Many independent researchers these days adopt the view that a long-lost civilization with advanced technology once ruled the land. And it was supposedly these people who built constructions like the pyramids and perhaps other mysterious tombs like Mastaba 17.

Perhaps their work can be distinguished not just for its quality, but for lacking any type of art or inscriptions whatsoever. This is in stark contrast to most structures throughout Egypt that are entirely covered in art and writing.

One popular theory is that this mysterious civilization got wiped out in a major cataclysm of some sort. But a good portion of their knowledge was retained, and the Dynastic Egyptians would spend the next few thousand years trying to follow in their footsteps.

Pyramids aside, there’s convincing geological evidence to support the theory that the Sphinx is far older than Dynastic Egypt. Furthermore, while unlikely related to Egypt, Turkey’s 12,000-year-old Göbekli Tepe has proven that humans were building advanced megalithic projects far longer than originally thought.

But if the 4th Dynasty pyramids really were the works of a long-lost civilization, that would make Djoser’s Step Pyramid simply an attempt at copying what was already at Giza! It’s certainly strange to think about.

And what about Khufu and Khafre? While historic documents prove that they were building at Giza, were they merely renovators and restorers? That’s a pretty big downgrade from being regarded as the greatest builders of the ancient world!

But if the pyramids of Giza and Dahshur were always there, why did it take until the 4th Dynasty for pharaohs to refurbish them and claim them as their own?

Why didn’t the 1st or 2nd Dynasty kings do it? And what about Sneferu? If the pyramids of Dahshur AND Giza were already there at the start of his reign, why didn’t he just claim the Great Pyramid?

Another structure that calls the whole lost civilization theory into question is the pyramid at Meidum. Its core structure resembles 3rd Dynasty construction techniques. But it utilizes the corbelled ceilings that can be seen at all other 4th Dynasty pyramids. It does indeed seem like a clear link between pyramids credited to the 3rd and 4th Dynasties.

Were all Pyramids Tombs?

With that being said, the existence of Meidum totally contradicts the ‘pyramids as only tombs’ theory favored by Egyptologists. Why would Sneferu need three tombs (or even cenotaphs)?

Perhaps the 4th Dynasty pyramids had some other purpose. As mentioned, the Great Pyramid in particular reveals highly accurate information about the precise measurements of the earth.

While its hard to say what purpose the others might have had, could the Egyptians have accomplished whatever their mission was by the end of the 4th Dynasty? And then go on to resume building pyramids as simple tombs from the 5th Dynasty onward?

The truth is that nobody knows for sure. But strangely, it appears as if the pyramid mysteries don’t concern mainstream Egyptologists all that much.

As John Anthony West writes, ‘In Egyptology, as in so many modern disciplines, all questions are believed to have ‘rational’ answers. If no evidence is available to provide a rational answer, the customary solution is to trivialize the mystery.’

But the mysteries of the pyramids are far from trivial. Solving them is not just important for the study of ancient Egypt, but for human history as a whole.

Additional Info

For anyone with a serious interest in pyramids, especially the less famous ones, be sure to pick up The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries by Mark Lehner. The book features plenty of pictures and comprehensive information on every pyramid the Egyptians ever built.

While Lehner is no doubt an expert on the topic, he’s about as ‘orthodox’ as they come, and he tends to shun any theory that could potentially upset the status quo. Contrary to the title of his book, he doesn’t manage to solve any of the mysteries we went over above.

To get the full picture of ancient Egypt, it’s important to read both orthodox and alternative sources. While not specifically about pyramids, Serpent in the Sky by John Anthony West is the best place to start for those wanting to delve deeper into the ancient Egyptian mindset. It’s a groundbreaking book that is a must-read before your visit to Egypt.

We’ve also covered most of Egypt’s prominent pyramids in previous guides:

- Stepping Inside the Step Pyramid of Djoser

- Saqqara: The Ultimate Guide

- Dahshur & Memphis: Entering the Bent Pyramid of Sneferu

- Giza: The Mysteries of the Pyramids and the Sphinx

- Visiting the Forgotten Pyramids of Abu Sir

- The Mysteries of Meidum & Mastaba 17

- Mazes and Mudbrick: The Pyramids of El Lahun & Hawara