Last Updated on: 13th November 2024, 08:49 pm

Gaziantep, with a population of nearly two million, is southeast Turkey’s largest city and among the largest in the country. Like many places in the region, it has a rich history dating back to prehistoric times. Compared to its neighbors, however, it has relatively few landmarks. But the excellent Zeugma Mosaic Museum, which displays some of the Roman Empire’s finest mosaics, is a must-visit.

Among Turks and an increasing number of foreigners, Gaziantep is also famous for its cuisine. While not the primary focus of this Antep guide, keep reading to learn more about the city’s most popular restaurant. And for practical info on accommodation and transport, check the very end of the article.

Note: Gaziantep was long known as Antep until the 20th century, and people in Turkey continue to use both names interchangeably.

Gaziantep Castle

A logical place to start your tour would be Gaziantep Castle, the largest landmark in the city’s historic district. The site is also home to one of the province’s oldest settlements.

This castle is just one of countless others you’ll encounter around Turkey. And while it’s relatively unremarkable visually, its history is rather unique. Not only has the mound beneath the castle been settled since prehistoric times, but the fortress played a pivotal role in an important 20th-century battle.

Archaeological findings from the mound date back to at least 3600 BC, though it was likely settled as far back as the 6th millennium BC. While at the Gaziantep Archaeology Museum (more below), you can find various Bronze Age artifacts discovered within the mound, including vases, bowls and jewelry.

A small castle atop the mound was first constructed during the Roman period in the 2nd century AD. Later in the 6th century, the Byzantines dug a moat around the hill and increased the number of bastions to twelve.

In medieval times, the castle was expanded by the Seljuks and later the Ottomans. The extant mosque and hamam, or bathhouse, at the top date back to these times.

Gaziantep Castle now doubles as something called the ‘Panorama Museum,’ entirely dedicated to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s War of Independence and Gaziantep’s role in it.

As you make your way to the top, you’ll pass through textual and video displays providing very detailed background info on the conflict. In total, the amount of text is immense, while the dim lights make it difficult to read. After trying for several minutes, my eyes got sore and I headed straight for the top.

But to briefly summarize the conflict, in 1920-21, the inhabitants of Antep managed to defend their city during a 10-month siege by the French army.

Following World War I and the downfall of the Ottoman Empire, various European powers sought to divide up Anatolia for themselves. But Atatürk and his War of Independence put a stop to that, resulting in an independent Republic of Turkey.

And it was Atatürk who granted the city of Antep with its new name, Gaziantep (gazi meaning ‘war hero’).

There’s not a whole lot to see at the top. You’ll find some remains of building foundations along with the ruins of the bathhouse, mosque and arsenal. You can also enjoy the views of the modern Antep skyline, but the city won’t be winning any beauty contests anytime soon.

- İstasyon Caddesi

- 8:30 - 17:30

- Closed Mon.

- 10 (as of 2020)

Around Şahinbey

The old quarters of Gaziantep are situated within a district called Şahinbey, located south of Gaziantep Castle. With plenty to see, you likely won’t be able to see everything if you only have a day in town.

The following guide, therefore, should help you decide where to devote your time. Also be sure to check the map above to see where each Şahinbey attraction is located.

Hamam Museum

Just near Gaziantep Castle, the Hamam Museum is worth a short stop, with tickets only costing 10 TL (as of 2020).

The museum is situated in an Ottoman-era hamam built in 1577. Here you can learn about the functions of each part of the bathhouse, along with the major roles hamams have played in Turkish and Islamic culture as a whole.

Of course, hamams aren’t merely things of the past. Most Turkish cities have plenty of active hamams to choose from if you want to try.

Gaziantep Mevlevihanesi Vakıf Müzesi

This former Dervish lodge dates back to the 17th century. The Mevlevi, or Dervish order, was founded in the 13th century by the Persian mystic and poet Rumi. And the Sufi order persisted for centuries following his death.

On the second floor, visitors can see mannequins dressed as Dervish musicians and dancers. Informational signage provides info about the history of the lodge and Rumi himself, while another room displays centuries-old copies of the Quran.

In the 20th century, Republic of Turkey founder Atatürk shortsightedly banned all such orders. And while the ban has since been lifted, the Whirling Dervishes no longer play a significant role in Turkish society, except for the occasional tourist-oriented performance.

Pisirici Mescidi ve Kasteli

In the southeastern portion of Şahinbey is an unassuming historical landmark that most people overlook. After all, it’s entirely underground.

Likely dating to the 13th century Seljuk Period, this subterranean chamber is known as a kastel. It served as a public water source and supposedly once provided water to a mosque.

The water was brought here via gently sloped manmade tunnels, connecting the city with the nearest natural water source.

Entry is free, while the only staff on hand is the security guard. While there’s now English signage on the walls, he’ll do his best to show you around anyway.

Sehrekustu Mansions

A short walk from the kastel are the Sehrekustu Mansions, a series of traditional houses built along a cobblestone street. It’s a pleasant place to explore, and a nice respite from the crowded, dusty streets of central Antep.

Kurtuluş Mosque

In the southwestern portion of Şahinbey is one of the city’s most interesting pieces of architecture. At first glance, it’s clearly a mosque. But upon closer inspection, something seems off. That’s because the elaborate structure was originally built as an Armenian church in 1892.

This particular area is called Bey Mahallesi, and it’s worth a quick walk around to see a couple of other church-turned mosques.

Gaziantep Emine Göğüş Mutfak Müzesi

The Gaziantep Emine Göğüş Mutfak Müzesi, not far from the castle, is a museum dedicated entirely to Gaziantep cuisine. Antep, in fact, is widely regarded as Turkey’s ‘food capital.’ Food-lovers from Istanbul or Ankara even sometimes fly over for the weekend just to eat here!

The museum, situated in a restored traditional house, contains bilingual info on Gaziantep’s most common dishes and their ingredients.

To most visitors, though, Antep cuisine is synonymous with two things: kebabs and baklava. One reason that the baklava here is considered Turkey’s best is because Antep is the country’s top producer of pistachios.

After my visit to the food museum, I decided to kill two birds with one stone by trying out one of the city’s most popular eateries: the İmam Çağdaş Kebab & Baklava Restaurant.

Antep Cuisine: My Strange Experience

At the İmam Çağdaş restaurant, I tried one of their recommended kebab dishes that included yogurt. It was indeed very delicious. But to be fair, it cost 42 TL: about double what these meals typically cost in Turkey.

I then paid an additional 20 TL for a mixed plate of baklava. Two of the pieces were quite tasty, while the other two tasted a bit strange.

Overall, it was definitely a good meal, and my time in Antep was only beginning. While not my primary reason for coming, I was looking forward to sampling various restaurants throughout my stay.

The next morning I ate a simple breakfast at my hotel. But by lunchtime, something started to feel off. And by the time I got to the Zeugma Mosaic Museum, I was battling waves of nausea. There was no doubt about it: I got food poisoning in Turkey’s food capital!

Thankfully, it was pretty mild as far as food poisoning goes. While I didn’t feel great, I was able to carry on with all my planned sightseeing for the next few days.

My appetite, though, had completely vanished. I couldn’t eat much more than a few pieces of bread each morning, skipping lunch and dinner entirely.

It wasn’t until my last evening that my appetite returned somewhat. I found a highly-rated but local lahmacun place near my hotel. If Gaziantep food was indeed as good as everyone says, even the small mom-and-pop restaurants should be amazing. But my lahmacun was … OK. It wasn’t even as good as what I’d had in nearby Urfa.

I continued traveling across Turkey for the next couple of months, but Antep remained the ONLY place where I got food poisoning. Later, when talking with a Turkish acquaintance about my experience, he told me ‘Oh, yeah, lots of people get food poisoning in Antep.’ (!)

Gaziantep Archaeology Museum

Largely overshadowed by the nearby Zeugma Mosaic Museum, the Gaziantep Archaeology Museum houses an impressive collection that shouldn’t be missed.

The museum focuses on the Neolithic age up through Roman times. And like the nearby Şanlıurfa Museum, it takes visitors through each section chronologically.

But as is the case with these regional museums, they only focus on findings from within the modern provincial borders. As such, it’s rather strange to read about the Neolithic age without any mention of nearby Göbekli Tepe!

The Gaziantep Archaeology Museum’s strong points are its Bronze Age and Iron Age collections. And a special focus has been placed on the Hittites, one of the world’s most influential civilizations of the late Bronze Age.

Based out of their capital of Hattusa in modern-day Çorum Province, the Hittites controlled most of Anatolia and much of the Middle East. At their peak, they were worthy adversaries of the ancient Egyptians. They fought many battles with them, such as the 1296 Battle of Kadesh during Ramesses II‘s reign.

But after the fall of the Hittite Empire in the late 12th century, numerous states rose from their ashes across Anatolia during the Iron Age. We now classify these states as ‘Neo-Hittite,’ as they used the Hittite language of Luwian and carried on many Hittite artistic traditions.

The Neo-Hittites thrived in southeastern Anatolia, including the area of Gaziantep. Many of the artifacts on display come from a place called Sam’al, or Zincirli Höyük, which was ruled by the Neo-Hittites in the 10th century BC.

Another Neo-Hittite center in Gaziantep Province was Karatepe in the southwest part of the province. And nearby was a massive sculpture workshop known as Yesemek.

Now an open-air museum, visitors can still wander through the area and check out various left-behind prototypes. While I didn’t get to visit myself, some of the works found there are on display at this museum.

Many of the pieces here depict the Hittites’ primary deity, the storm god Teshub. Interestingly, this god was also worshipped as Tushpa by the neighboring Urartians.

Also on display at the museum is a huge collection of Neo-Hittite orthostats, or stone slabs placed at the bases of walls. On many of these gigantic slabs, you can see the largely forgotten Luwian hieroglyphic script.

It bears no relation to Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the script was first used by the Bronze Age Hittites in addition to Mesopotamian cuneiform.

For a more comprehensive overview of the Hittites, stay tuned for our guide to the ancient capital of Hattusa.

The next major section of the museum covers the Hellenistic (330-30 BC) and Roman eras. Most of Gaziantep was controlled by the Seleucid Empire following the conquests of Alexander the Great. Large parts were then controlled by the Commagene Kingdom before being ceded to Rome.

The Gaziantep Archaeology Museum is worth visiting in tandem with the Zeugma Mosaic Museum. While the other museum almost entirely focuses on mosaics, here you’ll find many sculptures and funerary stela from Zeugma.

While the section on Gaziantep’s Islamic era is negligible compared to the pre-Christian selection, don’t miss the bizarre fountain lion statue from medieval times!

- İstasyon Caddesi

- 8:30 - 18:00

- Closed Mon.

- 10 (as of 2020)

Zeugma Mosaic Museum

The city of Zeugma was founded in the 3rd century BC by Seleucus I, general of Alexander the Great and founder of the Seleucid Empire.

But from 163 BC, it changed hands to the small but prosperous Commagene Kingdom, most known for the famous landmark of Mt. Nemrut. Then, during the reign of Commagene king Mithridates II (38-20 BC), Zeugma was ceded to the Roman Empire.

As it was strategically located by a bridge across the Euphrates River, it became a major city of up to 70,000 people. And Zeugma residents were no strangers to luxury, as their elaborate residences and bathhouses featured some of the finest mosaics of the ancient world.

But with the construction of the Birecik Dam, most pieces needed to be rescued due to the rising water levels. The Zeugma Mosaic Museum was constructed to house them, officially opening in 2011.

It now contains a staggering 800 m² of mosaics in total and is undoubtedly the top thing to do in Gaziantep.

Upon entry to the museum, those coming from the Mt. Nemrut area will notice a familiar scene. Two basalt stela salvaged from the ruins depict Commagene’s Antiochus I shaking hands with Mithra-Appolo and also Hercules.

Antiochus I was the builder of Mt. Nemrut, where’s he’s also entombed. Similar stela can be found there, and also at the nearby memorial for his father at Arsameias.

While there are a small handful of other carvings on display at the Zeugma Mosaic Museum, the focus is entirely on mosaics from here on out.

As mentioned above, you can find numerous sculptures from Zeugma at the archaeology museum.

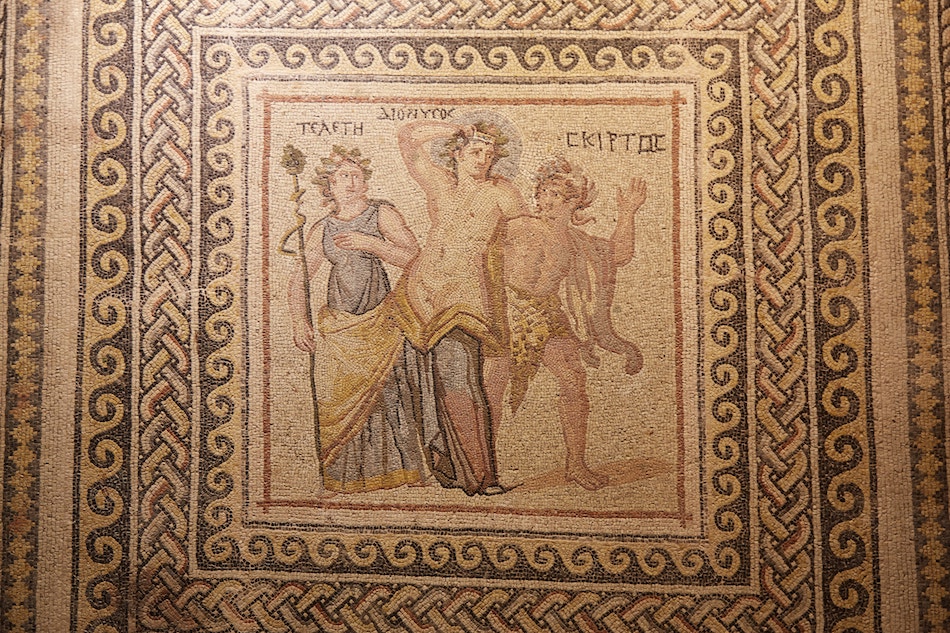

One of the first prominent pieces on display is the Dionysus Mosaic, dating back to the 2nd or 3rd century AD. Consisting of three large panels, the lefthand one featured a minimalistic depiction of Dionysus’s face surrounded by geometric patterns.

The middle panel, which is largely damaged, depicts the marriage of Dionysus and Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos.

Another highlight is the Oceanos and Tethys Mosaic, originally located on the floor of a pool in ‘The House of Oceanos.’ In Greek mythology, Oceanos was a Titan and father to all the world’s river gods.

Between him and his wife Tethys is a dragon called Cetos, a mythological creature that was also used locally to symbolize the Euphrates. Around the couple, meanwhile, are smaller figures representing Eros, Pan and various sea creatures.

Another well-preserved mosaic is that of Acratos and Euprocyne, a nymph who represented abundance. The piece was salvaged in 1998.

Additionally, the Zeugma Mosaic Museum also contains some surviving wall frescoes that were rescued, in addition to numerous pillars. Like most of the mosaics, they also date to the 2nd or 3rd centuries AD.

Other perfectly intact mosaics include a long series of Euphrates river gods. Continuing with the nature deity theme, there’s also a beautiful rendition of Gaia, or Mother Earth, featured in the center of interwoven geometrical shapes.

Among the most impressive pieces at the Zeugma Mosaic Museum is a famous scene from the Iliad involving Achilles. Though his mother Thetis tried to disguise him as a woman to prevent him from going off to the Trojan War, Odysseus learns of the deception.

The scene here takes place in the court of King Lycomedes (far left), where Achilles was disguised as one of the king’s daughters. But after Odysseus (far right) blows a battle sounding horn, Achilles (center right) instinctively picks up a shield and spear, blowing his cover.

The Zeugma Mosaic Museum contains far too many impressive pieces to be fully covered here. But as nice as the museum is, one can’t help but imagine what a pleasure it would’ve been to see these mosaics in their original location.

Many well-preserved pieces come from a building called the Poseidon Villa, dating from the 3rd century. One of them depicts Dionysus yet again. The god was highly esteemed in Zeugma, as he was believed to have been the first one to build a bridge across the Euphrates.

Up on the second floor, meanwhile, in its own special darkened room, is the museum’s most famous piece. And rather ironically, it’s just a small fragment!

Dubbed the ‘Gypsy Girl’ mosaic, probably because of the gold earring, nobody actually knows who the face is supposed to represent. It could be a mythological figure or perhaps a historical one. And we’re not even sure if it’s a man or a woman.

But the mystery is a big part of its allure. It’s now an unofficial symbol of the city, while you’ll spot the Gypsy Girl in promotional posters all across the country.

Elsewhere around the second floor, you can find the Kidnapping of Europe Mosaic, featuring Zeus disguised as a bull, and yet another Dionysus bust.

But that’s not all. Just when you think you’ve seen everything, you notice an elevated walkway leading to an entirely separate building! While also filled with mosaics, they mostly come from other places besides Zeugma.

They’re largely void of mythological scenes or faces altogether, instead consisting of simple geometric patterns. As they’re not nearly as compelling, you’ll likely find yourself rushing through this extra section.

- Tekel Caddesi

- 8:30 - 17:30

- Open daily

- 30 (as of 2020)

Pin It!

Additional Info

If you stay relatively close to Gaziantep Castle, you’ll be able to reach most of the locations in this Antep guide on foot.

While the Zeugma Mosaic Museum is the city’s main attraction, the area around there lacks amenities for tourists.

I’m a budget traveler who prefers private rooms with private bathrooms. I stayed in a place called Yunus Hotel, which is one of the better-known budget hotels in the city.

The location was good and the main guy at the desk was friendly, but there were some problems with the room. The toilet leaked while my doorknob entirely came off at one point!

If you don’t mind searching around a bit, I noticed many other hotels in the same area that are not listed online.

Many of the locations featured in the Antep guide are walkable, especially if you’re staying relatively close to the castle.

Unlike other Turkish cities of its size, Antep has no tram system, leaving bus and taxi as your only option for longer distances.

Antep has adopted the cashless system for its buses. But don’t count on actually finding a transport card vendor near a bus stop. As most drivers won’t accept cash, you’ll have no choice but to track down one of these elusive machines.

Furthermore, buses only have the names of local neighborhoods (not specific landmarks) posted on them, so visitors won’t have any idea of which one to take. The buses are really only worth dealing with to get to the otogar (bus terminal).

Gaziantep has an airport situated about 20 km southwest of the city. It connects with most major cities in Turkey and even some international locations.

Gaziantep has a rail system, but service has been suspended for the past few years. Be sure to check for updates closer to your visit.

As the southeast’s largest city, Antep is very well connected by bus. You can get here from all over the southeast region as well as long-distance from other areas. Leaving the city, I was even able to travel directly to Göreme in the Cappadocia region.

For those coming by bus, the otogar (bus terminal) is about 6 km north of the city center. As of 2020, a taxi ride should cost about 25 TL.

Public buses running from the otogar to the center are also an option, but it’s unclear which bus goes where. I tried hopping on a random bus when returning to the city from a day trip. It did eventually end up in the center, but only after a long detour through some random side streets.

Gaziantep is the westernmost city of Turkey’s southeast, and therefore serves as most people’s gateway to the region.

But having visited every major city of the southeast, Antep turned out to be my least favorite. Except for a few small sections of the old quarters, the city is quite hectic and rather ugly, primarily consisting of hastily-built concrete eyesores.

And aside from its unpleasant atmosphere, it can’t compete with its neighbors like Urfa in terms of attractions. The Archaeology Museum is nice, but not as good as Urfa’s. And while the Zeugma Mosaic Museum is great, it’s not as exciting as seeing mosaics in their original location, as you can also do in Urfa.

And as mentioned above, the food is quite good overall. But the city really needs to work on improving hygiene and sanitation. Many people seem to get food poisoning, including me.

So is Gaziantep worth it? If you’re traveling by land and will be passing through anyway, it’s worth spending a day to see the Zeugma Mosaic Museum and other places mentioned above.

But if you’re short on time and flying, it’s best to skip Antep altogether, heading straight for Urfa, Diyarbakır or Van instead.

While the Turkish government isn’t quite as extreme as China when it comes to online censorship, you’ll probably want a decent VPN before your visit.

I’ve tried out a couple of different companies and have found ExpressVPN to be the most reliable.

Booking.com is currently banned in the country (at least when you search for domestic accommodation). However, there are actually quite a few Turkish hotels listed on there anyway. And many them don’t even appear on Hotels.com, which hasn’t been banned.

Over the course of my trip, I ended up making quite a few reservations with Booking.com and was really glad I had a VPN to do so.

Another major site that’s banned is PayPal. If you want to access your account at all during your travels, a VPN is a must.

While those are the only two major sites that I noticed were banned during my trip, Turkey has even gone as far as banning Wikipedia and Twitter in the past.