Last Updated on: 25th September 2024, 01:22 pm

Karnak, the largest temple ever built by the ancient Egyptians, was in constant use for over 1,500 years. It was in a perpetual state of construction, which is quite fitting, as Karnak Temple was consecrated to creation itself. Accordingly, the complex is massive, and finding your way around can be confusing. This following Karnak Temple guide covers everything there is to see along with the best route to take during your visit.

Karnak, in fact, is considered to be the world’s second-largest temple complex after Cambodia’s Angkor Wat. And the two make for an interesting comparison. While Angkor Wat follows a symmetrical plan that was clearly designed from the start, Karnak seems strikingly chaotic in comparison. Were the builders just making it up as they went along?

Not quite. Egyptian temples typically started with their central sanctuaries and then grew outward from there. This central chapel was considered to be the temple’s ‘seed,’ and its geometry and proportions set the standard for all future constructions.

Richard H. Wilkinson, author of The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt, observes that when measured in Egyptian cubits, the rate of growth at Karnak follows the Fibonacci mathematical sequence. The sequence, in which each successive number equals the sum of the two numbers preceding it (1, 2, 3, 5, 8, etc.) is found all throughout the natural world.

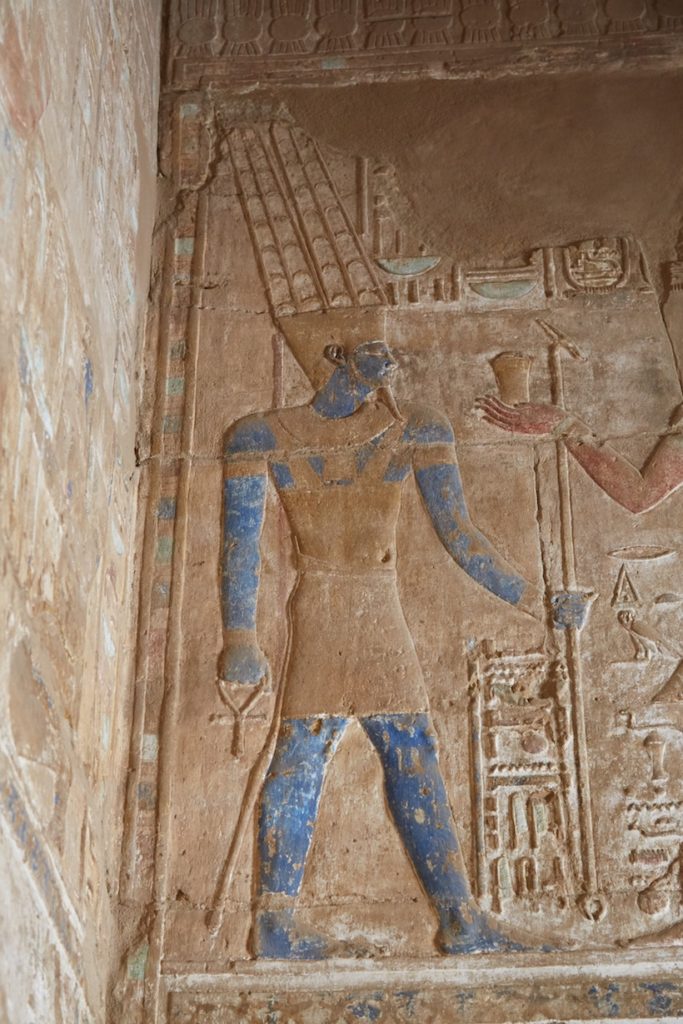

Fittingly, as these geometrical proportions at both Karnak and in nature, are invisible to the eye of the observer, the temple was consecrated to Amun, or ‘the Invisible One.’ Amun was worshipped as the ‘breath of life,’ or the unseen force behind all creation.

But paradoxically, Amun imagery can be seen all over Karnak! He’s typically depicted wearing his double-plumed headdress, while he also takes the form of the ithyphallic Min-Amun, representing creation manifest as sexual energy. As we’ll cover below, other sections of Karnak are dedicated to the two other deities of the Theban triad, Mut and Khonsu.

Karnak is a chronologically confusing place, and we’ll be jumping back and forth across the timeline of Egyptian history. While we’ll briefly cover the significant pharaohs and their roles below, studying the basics of Egyptian history before your visit is highly recommended.

Visiting Karnak Temple

WHEN TO VISIT: Karnak and Luxor Temple can both be visited on the same day. Logistically-speaking, it makes more sense to start with Luxor Temple in the early morning before visiting Karnak. That temple is close to most of the hotels on the east bank and it’s just by the ferry port for those coming from the west.

However, if you’re interested in buying the Luxor Pass (more below), it can only be purchased at Karnak and not at Luxor Temple.

Luxor and Karnak temples are about thirty minutes apart on foot. After years of excavations, the 2.7 km Avenue of the Sphinxes is finally open to the public, and visitors can now use it to walk between the two temples – just as the pharaohs did in ancient times.

RECOMMENDED ROUTE: Upon entering the temple, everyone will start their visit from the far western end of the complex. You’ll begin at the first pylon (double gate-like structure). The main east-west axis of the temple features pylons 1-6, while the southern portion of the temple has pylons 7-10.

Walking through the first pylon, you’ll arrive at the Great Court, which also contains a few minor temples within it.

Next, you’ll walk through the Hypostyle Hall, often regarded as Karnak’s main highlight. Keep heading east to check out the two standing obelisks in between the fourth and fifth pylons.

Shortly afterward, you’ll get to the small but highly significant central sanctuary. Further east, you’ll reach a spacious courtyard with the unique Festival Temple of Thutmosis III.

You’re now finished with the main portion of Karnak Temple. From here there are still the northern and southern sections to explore. Let’s check out the north first.

After briefly checking out the far eastern end of the complex, swing around the north to visit the Temple of Ptah. And nearby to the west is the fascinating Open-Air Museum.

Now backtrack to the obelisks and head south. You’ll see a fallen obelisk just next to the Sacred Lake.

Keep heading south to explore the southern pylons (7-10). Then head west to visit the Temple of Khonsu.

During your visit, if the gates near the Temple of Khonsu or the 10th pylon are open, you should be able to walk directly south to the Precinct of Mut. If not, you’ll have to exit Karnak the way you came and walk about 20 minutes through town to get there.

Entering the Temple

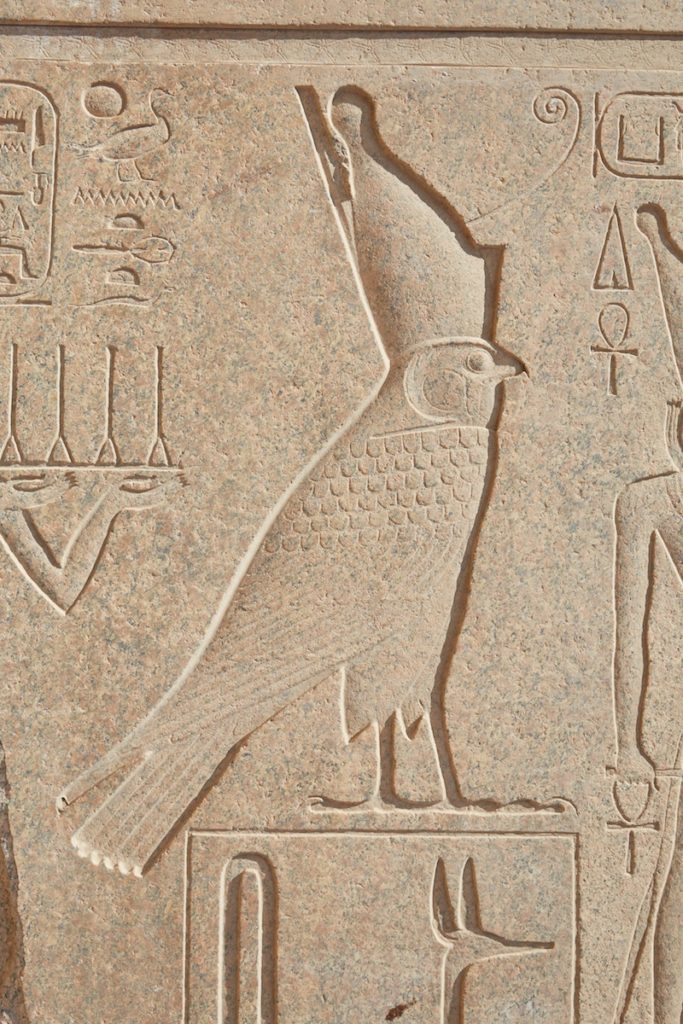

Arriving at the temple through the main entrance, you’ll walk through a processional path lined with sphinxes. But rather than the typical human face on a lion’s body, these sphinxes have the head of a ram.

The ram was a symbol of Amun, the prominent deity worshipped in Thebes. Amun was an ancient primordial god who appeared in Egyptian creation myths. But it wasn’t until the Middle Kingdom period that Amun replaced the war god Montu as the city’s patron deity.

Notably, Amun’s replacement of Montu, who was symbolized by a bull, happened around the shift from the Age of Taurus to the Age of Aries. The shift took place in 2160 BC, right around when the 11th Dynasty reunified Egypt and made Thebes/Luxor the capital.

At the end of the path is the outermost pylon – a gate which resembles the hieroglyph for akhet, or horizon. As such, pylons symbolized the sunrise, though they probably also came in handy as lookout towers.

While we now call it the first pylon, it was actually the last one built. It likely dates to the 30th Dynasty (380-343 BC), the last ever native Egyptian dynasty. Curiously, this pylon was never completely finished.

The Great Court

Next, you’ll enter the Great Court, a spacious area with a whole lot to see. In the center is a double colonnade built by Nubian/Ethiopian king Taharqa (690 – 664 BC). Nearby is an alabaster altar and some impressive statues.

Elsewhere in the court, you can find some more ram-headed sphinxes along with some additional shrines and temples (more below).

One of the most peculiar aspects of this section is the remnants of the mudbrick ramp. These ramps likely functioned as a type of scaffolding, allowing masons and carvers to work on the higher levels of the walls. But why was it never dismantled?

While we may never know for sure, it’s possible that at Karnak and at other temples, the Egyptians intentionally left certain sections unfinished. As mentioned above, Karnak signified perpetual creation. With that in mind, it’s quite fitting that it was never fully completed!

Amun/Mut/Khonsu Shrine

To the left of the court is a triple shrine built by Seti II (1214 – 1204 BC) which long predates the construction of the pylon. It’s dedicated to the Theban triad of Amun/Mut/Khonsu (as is the entire Karnak complex as a whole).

On the walls inside, you can find imagery of Amun as a ram on his barge in the night sky. This is further evidence that his rise to prominence in Thebes marked the transition of Taurus into Aries.

It’s likely that these rooms would hold ceremonial barques of each deity. During ceremonial processions, they’d be ritually cleansed here before moving deeper inward.

Ramesses III Temple

On the far right of the court is the entrance to an Amun temple built by Ramesses III. This temple within a temple features statues of the king as Osiris and a Hypostyle Hall with eight papyrus-bud columns. The end of the temple, meanwhile, contains shrines for Amun, Mut and Khonsu.

As you can also see at Medinet Habu, Ramesses III’s mortuary temple on the west bank, his hieroglyphs were carved incredibly deep for some unknown reason.

Just outside of the Ramesses III temple, to the east, is a small portico dedicated to Pharaoh Soshenq of the 22nd Dynasty. It was Shoshenq who defeated Rehoboam, son of Solomon, in a battle that was mentioned in the Old Testament.

Just outside on the outer wall, you can see some of these Biblical battle scenes featuring Shoshenq. Further along the outer wall, meanwhile, are scenes depicting Ramesses II’s victory in the Battle of Kadesh.

Battle scenes are a common motif at nearly all Egyptian temples. In addition to being historical to some degree, these scenes typically symbolized the forces of light vanquishing the forces of darkness.

For now, head back inside the Great Court and walk toward the second pylon. The pylon was originally built by Ramesses II and then extensively repaired by the Ptolemies.

It’s curious that the Ptolemies repaired the second pylon but never bothered to complete the first. As mentioned above, this was likely deliberate and for symbolic reasons.

The Hypostyle Hall

Karnak’s Hypostyle Hall is considered one of Egypt’s great masterpieces. It was begun by Ramesses I, the founder of the 19th Dynasty, during his brief one-year reign. Work was then continued by his son, Seti I (1306-1290 BC).

Not too much is known about Seti I, and his reign is largely overshadowed by that of his famous son, Ramesses II. But Seti I is responsible for some of Egypt’s greatest architectural and artistic gems. These include the temple at Abydos, his tomb in the Valley of the Kings, and of course, this Hypostyle Hall.

As is the case with many of Seti I’s creations, this hall was later fully completed by Ramesses II.

The spacious hall stretches out to 103 x 53 meters and contains 134 massive columns. The columns represent papyrus thickets which sprang from the primeval swamp (i.e. physical creation).

While the room is largely open to the sky now, it was originally dark and shadowy, just as one would imagine a primeval swamp to be. The original atmosphere can still be experienced somewhat in certain sections.

This awe-inspiring structure is likely where you’ll be spending most of your time at Karnak. (Of course, this is where most of the tour groups tend to linger as well.) It’s worth making repeated visits here throughout the day to experience it in different lighting conditions.

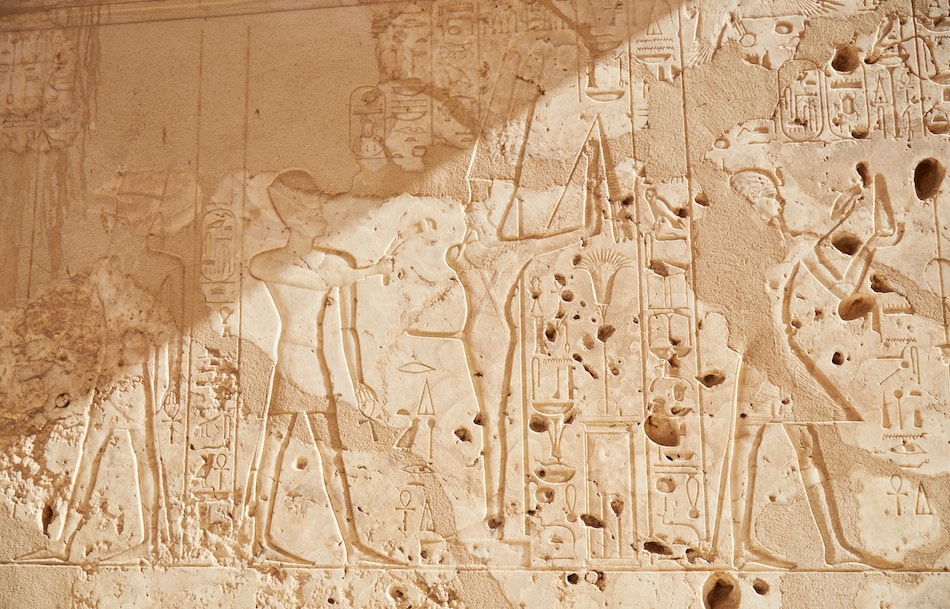

The inner walls are entirely decorated with intricate relief carvings, many of which depict royal ceremonies that took place here. Originally, only a few would’ve been visible at any given time depending on where the sun was shining.

As mentioned, some of Ramesses II’s military campaigns can be seen on the southern exterior wall. But Seti I’s battles have also been immortalized in the north.

By looking at an overhead map of the columns, one can see that the central rows each have six columns, a number used to represent time and space. The two rows of columns on either side of them, meanwhile, have seven columns each – a number associated with process and growth.

On either side, there were then six rows of nine columns each. Nine represented the Great Ennead, the primordial beings who emerged at the beginning of creation.

According to symbolist researcher John Anthony West, the interplay between 6, 7 and 9 was likely deliberate given the Hypostyle Hall’s association with physical creation.

The Obelisks

At the end of the Hypostyle Hall is the third pylon, mostly built by Amenhotep III of the 18th Dynasty. Interestingly, it was largely comprised of re-used blocks from earlier constructions. Many of the chapels that were recently rebuilt for the Open-Air Museum (more below) were originally demolished and used for this pylon.

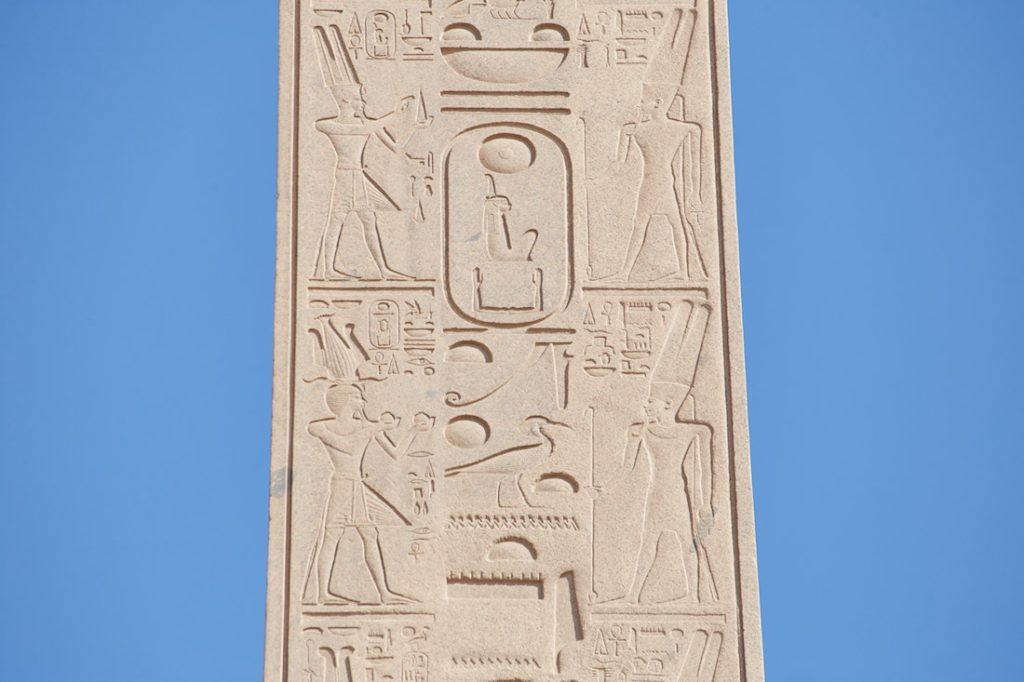

Past the third pylon is a space known as the Transverse Hall. And shortly after that is what’s left of the fourth pylon, beyond which is an obelisk erected by Thutmosis I.

Obelisks were symbols of the sun, and also likely symbolized the backbone of Osiris. They date back to the Old Kingdom, but took the form we see here from the Middle Kingdom onward. Amazingly, each obelisk is comprised of a single block of granite shipped all the way from Aswan!

Egyptologists have theorized that the ancient builders used a combination of mudbrick platforms and sand-filled holes to set them in their place. But until we can replicate these methods on the same scale, nobody can say for sure.

Nearby is an obelisk erected by Hatshepsut, Thutmosis I’s daughter. At 29.56 m, it’s the tallest obelisk which still stands in Egypt.

The world’s tallest, however, currently stands in Rome. It was first carved by Thutmosis III, Hatshepsut’s nephew and co-regent, and also came from Karnak. (Istanbul’s Obelisk of Theodosius comes from Karnak as well.)

Interestingly, at the time Hatshepsut’s obelisk was erected, this would’ve been Karnak Temple’s western extremity. Later, after Hatshepsut’s death, Thutmosis III built a wall around it, obscuring most of it. Yet his true motives remain unclear.

Thutmosis III destroyed many of Hatshepsut’s public monuments throughout Egypt (though he left her mortuary temple intact). As Hatshepsut was a female pharaoh, some blame Thutmosis III’s actions on misogyny.

Others believe that they may have had a rocky relationship. Hatshepsut had taken the throne for herself when Thutmosis III, the rightful heir, was deemed too young to rule. Even though they technically ruled as co-regents, Hatshepsut was the main one in charge up until her death.

Notably, even after Thutmosis III built the wall, the upper portion of the obelisk would’ve still been visible. So why didn’t he pull it down? We’ll never know what really happened between these two. But it’s possible that Thutmosis III’s actions were simply fueled by a desire to secure his legacy rather than out of spite.

Considering both the size of the obelisk and the hardness of granite, the level of detail in the carvings is astonishing. Further south is another one of Hatshepsut’s obelisks which has since fallen. And it’s much easier to get a look at the carvings from up close there.

But to avoid getting disoriented, let’s continue heading east for now and save the fallen obelisk for later.

The Holy of Holies

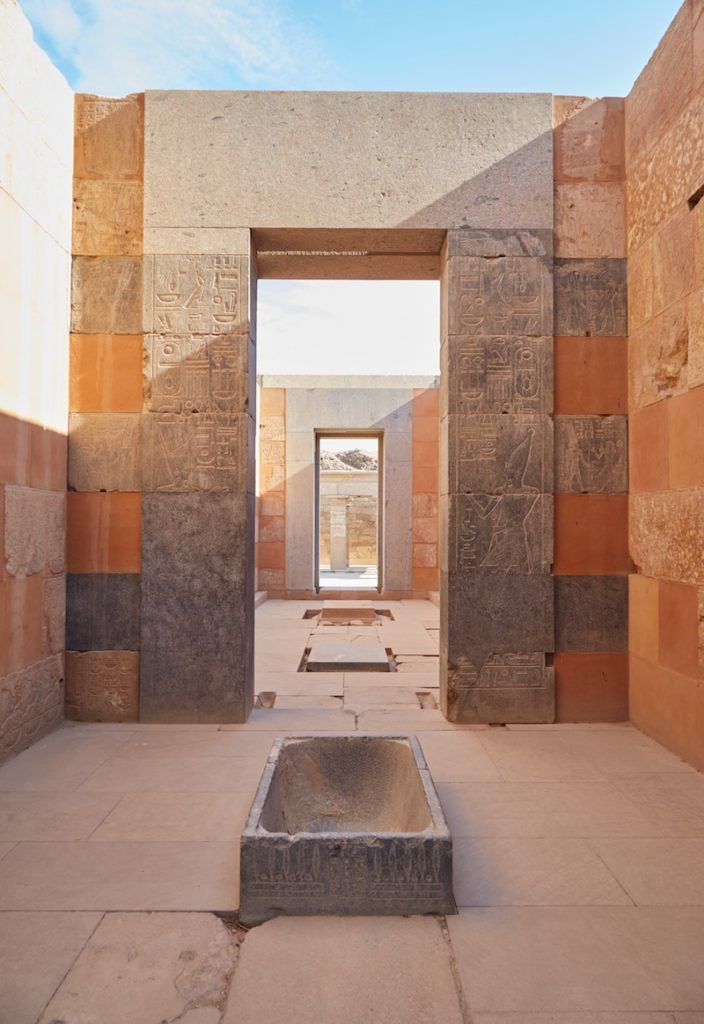

Heading east, you’ll reach the central sanctuary – Karnak’s ‘Holy of Holies.’ Given the grandeur of the columns, pylons and obelisks, the significance of this unassuming little shrine may not sink in at first. But this was Karnak’s most sacred structure and the spiritual epicenter of Egypt for centuries.

But what we see today is not the original structure. The first central sanctuary was built during the Middle Kingdom and then replaced with one built by Thutmosis III. And then, over a thousand years later, Alexander the Great’s brother Philip built the shrine we see now.

Many of Thutmosis’s blocks were reused, however. And even some of the original inscriptions have been left untouched.

The central pedestal would’ve been where Amun’s symbolic barque was placed during ceremonies. The ceiling is adorned with stars, while the carvings on the walls are of the standard ceremonial variety. They depict Amun (and the erect Min-Amun) receiving various offerings.

While fairly ordinary in appearance, much of the sanctuary’s power lingers to this day, which many people comment on upon entry.

As mentioned above, it’s likely that the measurements of this sanctuary set the standard for the proportions by which the rest of Karnak was built.

On either side of the Holy of Holies are some sandstone sanctuaries built by Hatshepsut. And there are also two impressive granite pillars around here. The one to the north is shaped like papyrus and represents Lower Egypt, while the southern pillar resembles a lotus and represents Upper Egypt.

There are also some colossal statues of Amun and his consort, Amunet, that were dedicated by Tutankhamun. But these were under renovation during my visit and obscured by a tarp.

The Festival Temple of Thutmosis III

In the back of the sanctuary is a courtyard containing Middle Kingdom artifacts. In fact, it was likely here that the very first incarnation of Karnak once stood. All around are many chambers and rooms of an unknown purpose, and there are plenty of interesting carvings to discover.

The focal point of this area today is the Festival Temple of Thutmosis III. Notably, like the other kings from his era, he also had a mortuary temple over on the west bank (now largely in ruins). It seems that this temple, then, was primarily built in dedication to Amun but also in remembrance of the king’s military exploits.

Thutmosis III set off on over a dozen foreign military campaigns, solidifying the largest Egyptian Empire that was known up to that point.

The temple remains in great condition, and it’s also considered to be highly unique. The columns take on an unusual form that can only be seen here.

They’re often described as ‘tent poles.’ Some Egyptologists suspect that Thutmosis chose them out of nostalgia for his military campaigns. The influential symbolist researcher Schwaller de Lubicz, on the other hand, had a different theory. He suggested that these columns function as inverse versions of typical papyrus columns, with the reverse tapers representing the void.

So in contrast to the Hypostyle Hall, which represents the creation of matter out of spirit, this temple may represent the exaltation of matter back into spirit. (This structure is by far the older of the two, however.)

The colors of the ceiling and on the columns remain vibrant. There’s also a shrine dedicated to Amun with excellent relief carvings. Notice how Amun was often depicted as blue-skinned, much like the gods of Hinduism!

Directly behind the Festival Temple is a sanctuary with three chambers, one of which contains three papyrus columns. This room today is known as the ‘Botanical Gardens’.

The walls are carved with exotic plants that Thutmosis III observed in Syria – at least according to an inscription. Strangely, many of the plants are actually African!

The Eastern Edge

The very eastern edge of the Karnak’s main east-west axis doesn’t have a whole lot to see. But it’s still worth a brief walk around. Behind the Festival Temple of Thutmosis III is a temple built by Ramesses II, now largely in ruin.

Many of the other ruins are indistinguishable. But further east, there’s a small Osiris temple built by Osorkon IV of the 22nd Dynasty. And nearby you can also see a good portion of the original mudbrick wall which surrounded the entire temple.

The far eastern gate was constructed by Nectanebo I, the founder of the 30th Dynasty – the very last native Egyptian group of rulers. But this area was probably the eastern delineation of Karnak in earlier times as well.

One pharaoh, however, decided to build even further east than this. It was the ‘heretic king,’ Akhenaten. He built a temple to the Aten sun disk before moving the capital entirely to Amarna. Perhaps he wanted his structure to be closest to the rising sun each morning.

But following his death, his successors usurped the temple’s stone to construct the ninth pylon to the south (more below). Supposedly, there are some old stones still lying around in the dirt, but the eastern gate was locked during my visit.

From here you have the choice of either heading north or south. In this Karnak Temple guide, we’ll be checking out the north side first.

The Temple of Ptah

The Temple of Ptah is a fascinating little temple that most visitors to Karnak miss entirely. The temple was originally built by Thutmosis III and was then renovated and enlarged by Pharaoh Shabaka and the Ptolemies. The Greek influence can clearly be seen in the floral capitals of the columns.

Ptah is a very ancient god who was the patron deity of Egypt’s prior administrative capital, Memphis. Moreover, he was revered as the divine architect of both heaven and earth and he represented the creative fire.

While Karnak and Luxor as a whole were most definitely Amun’s domain, older gods like Ptah were never forgotten.

There are some excellent carvings both outside and inside the temple. In the central sanctuary, meanwhile, is a statue of Ptah himself. Sadly, he’s now headless.

You’ll likely find the room next door to be locked, but you won’t regret tracking down a guard to open it up for you. (Be sure to have some small change handy.)

In the other sanctuary stands a fully intact black granite statue of Sekhmet, Ptah’s consort. During my time in Egypt, I visited countless temples and shrines, but this is the ONLY place where I encountered a fully intact statue inside of a sanctuary!

The guards let me get up close to the towering statue, but I didn’t dare touch it. The ancient Egyptians believed that divinities could inhabit their statues, and this particular carving would’ve been brought offerings for centuries as if it were a living god.

Outside the temple and further to the north lies the Precinct of Montu dedicated to the original patron deity of Thebes/Luxor. It was off-limits during my visit, however. But further west from the Temple of Ptah is another gem of Karnak that shouldn’t be missed.

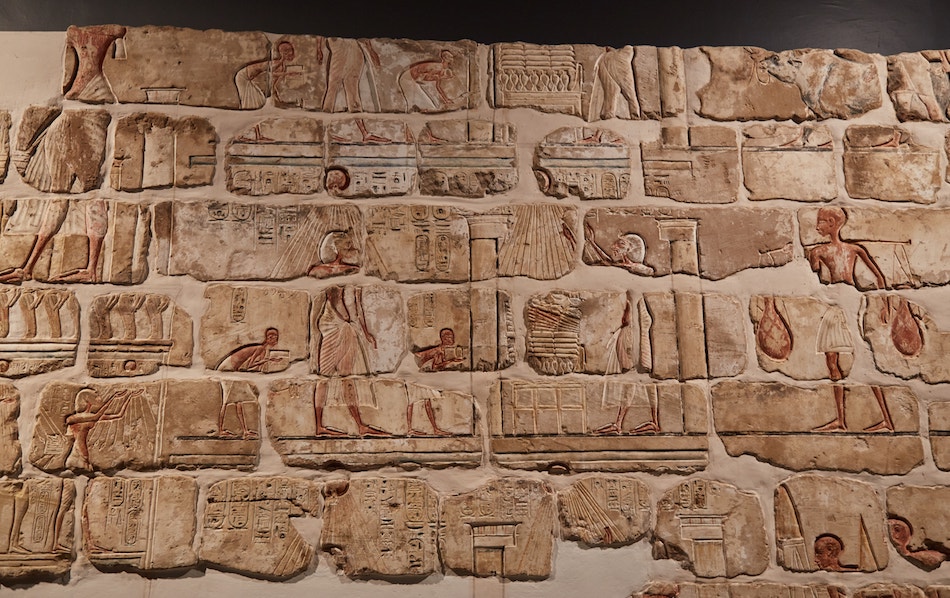

The Open-Air Museum

As mentioned above, the third pylon by the Hypostyle Hall consisted of usurped stone from the chapels of prior rulers. Amazingly, archaeologists have managed to salvage many of the original stones and entirely recreate the chapels.

They’re now on display at an open-air museum just north of the Great Court. The area also contains plenty of carved stones that were discovered all throughout Karnak.

The main highlight here is the White Chapel of Senusret I (also known by his Greek name Sesostris). Though Senusret I built a pyramid in Lower Egypt at Al Lisht, he also constructed here at Karnak. In fact, this structure is likely Karnak’s oldest!

The limestone chapel appears simple and unassuming, but there’s more to it than meets the eye. The platform doubles as a measuring rod for various units and subunits of the Egyptian measuring system. And there are also inscriptions detailing the precise measurements of Egypt’s various nomes, or territories.

According to researcher Lucie Lamy, the proportions of the chapel reveal that the Egyptians had advanced geodesic knowledge, or knowledge of the precise measurements of the earth. A detailed explanation, however, is rather complicated and beyond the scope of this guide. The Great Pyramid’s measurements also reveal similar knowledge.

The carvings along the chapel are of an extremely high quality. The central altar, meanwhile, likely held the king’s solar barque during the Heb-Sed festival, the special ceremony for kings who reigned 30 years or longer.

Nearby is an alabaster chapel of Amenhotep I, while another famous chapel is the red quartzite ‘Chappelle Rouge’ of Hatshepsut. There are also a couple of other New Kingdom-era chapels on display as well.

From here you’ll want to backtrack through the central part of the temple to get to the southern portion. Enjoy another walk through the Hypostyle Hall and then return to the obelisk of Hatshepsut and make a right.

The Sacred Lake Area

Just before the Sacred Lake, you’ll encounter a broken part of Hathsepsut’s other obelisk. The obelisk is famous for the ringing sound it makes when struck. Granite is a highly resonant stone and some researchers suspect that it was highly coveted by the ancient Egyptians for this reason.

While in the past, visitors could get right up to it, the obelisk is sadly roped off today. But you can at least admire the fantastic details of the engravings.

It’s hard to believe that such detailed carvings were achieved with nothing but copper chisels, as Egyptologists claim. And it’s highly unlikely that anyone could replicate these designs today without a much harder metal.

Next, turn your attention to the huge Sacred Lake, a common feature at many Egyptian temples. This seems to be one of the only ones currently filled with water. And at over 9,000 square meters, it’s also one of the largest.

The lake symbolized the primordial waters of Nun at the very beginning of creation (very much like the lakes or ponds at Hindu temples). While hard to see today, the masonry of the walls of the lake’s enclosure also forms the shape of a wave.

Northwest of the lake, there’s a huge stone scarab beetle (a prominent solar symbol) placed by Amenhotep III. The carving beneath it depicts the king making offerings to Atum of Heliopolis.

Nowadays, it’s common to see tourists encircling the beetle seven times. Supposedly, this is meant to solve one’s love problems!

The Southern Pylons

The north-south axis of pylons seven through ten isn’t nearly as remarkable as the main portion of Karnak Temple. But it’s still worthy of a walk around, followed by a visit to the Temple of Khonsu further west.

The courtyard in front of the seventh pylon, in particular, is noteworthy for a remarkable discovery made there in the early 20th century.

The Karnak Statue Cachette

According to an ancient papyrus scroll, Karnak Temple was once home to a whopping 86,486 statues! This number was long doubted by scholars, however. That is until 1903, when archaeologist George Legrain made an amazing discovery in front of Karnak’s seventh pylon.

In this single location, he found a cache of more than 20,000 statues. There were around 700 made of stone and 17,000 made of bronze. Many of these statues, which include carvings of prominent pharaohs, are now on display at the Cairo Museum and the nearby Luxor Museum.

The reason for such a mass burial of statues, however, remains a mystery. Some suspect that even such a huge temple complex as Karnak eventually became too crowded with them. And perhaps they were buried with proper ritual sometime during the Ptolemaic era, as Ptolemaic statues make up the most ‘recent’ works in the cachette.

The oldest date back to the Old Kingdom (including a statue of Nyussere!), though most are of New Kingdom-era pharaohs. The most impressive of the bunch is that of Thutmosis III, which shouldn’t be missed at the Luxor Museum.

The ninth pylon, while not all that impressive today, is also of special interest. The pylon was built by Horemheb, the last king of the 18th Dynasty. But it was largely made up of blocks from Akhenaten’s Aten Temple that he built just east of Karnak (see above).

Much of the artwork, which was inscribed on what we now call talatat blocks, was discovered and reassembled. It’s now on display at the Luxor Museum, in addition to some of Akhenaten’s bizarre colossal statues. (Learn more here.)

At the far southern end of the complex, you’ll find the Festival Temple of Amenhotep II, a militaristic king who loved to show off his physical strength and hunting skills. The temple is largely ruined, especially when compared with that of his father, Thutmosis III.

The southern gate was locked during my visit, but it should be opened sometime in the near future. The sphinx-lined path beyond it leads directly to the Precinct of Mut. Annoyingly, while the Mut area is still open, one has to exit Karnak and take a long detour through town to get there.

For now, let’s head west to visit the impressive Temple of Khonsu.

The Temple of Khonsu

Khonsu, as mentioned above, is part of the Theban triad together with Amun and Mut. The deity is sometimes depicted as having a hawk head and at other times as human. In any case, Khonsu is associated with the moon and lunar cycles.

Despite being a male deity, Khonsu is also typically associated with things like fertility, healing and childbirth.

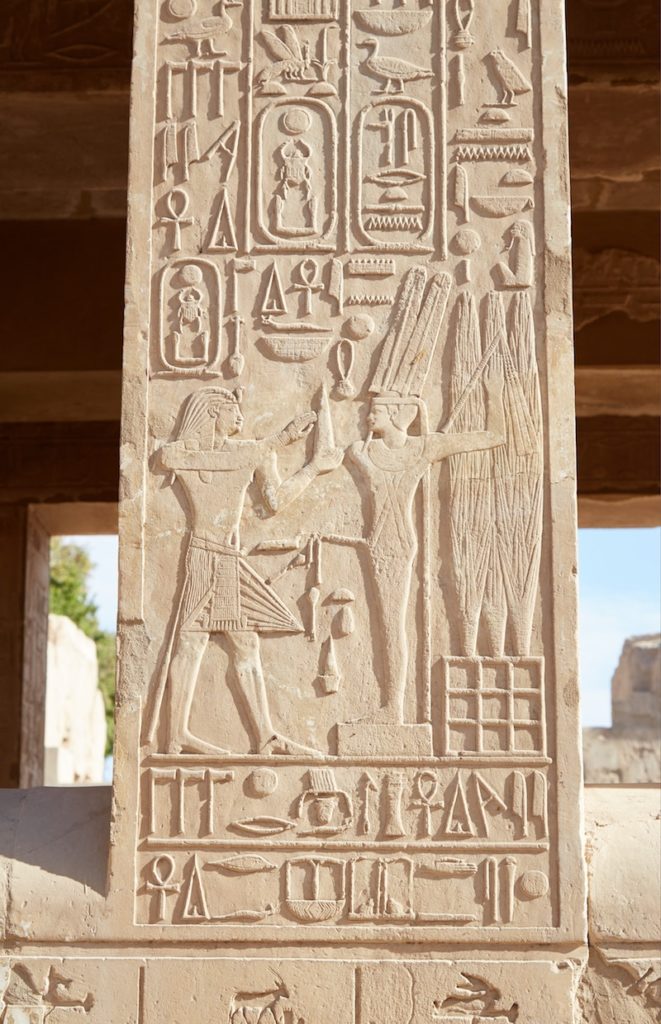

The Temple of Khonsu was started by Ramesses III but most of the reliefs were finished by later successors.

The forecourt contains a series of thick columns, while there are even more in the vestibule. The reliefs are pretty typical and mostly depict royals presenting offerings to divinities. But they’re very well preserved and worthy of close attention.

During my visit, much of the temple’s interior was roped off and inaccessible. But as common at Egyptian temples, the guard will happily grant you VIP access in exchange for a small tip. The guard here even led me to the roof, which provides a clear view of the staggering amount of stones recovered from around the complex.

The view from above reveals how there was once even a lot more at Karnak than what we can see today. Visitors are free to walk around this area, which functions as an additional open-air museum.

Just nearby is the small Ptolemaic-era Temple of Apet. Apet was the hippo goddess of fertility. In fact, the entire temple complex of Karnak, given its link with physical creation, was also commonly associated with Apet. In ancient times, Karnak was called Apet-Sut, or ‘Enumerator of the Places.’

While the door was locked during my visit, I could peek in through the side screens. There were some Ptolemaic-style Hathor columns in addition to colorful reliefs.

The Precinct of Mut

As mentioned above, the Precinct of Mut is directly across from the final, southernmost gate of Karnak. If the gate opens up someday, it should be a quick and straightforward walk to get there.

If not, exit Karnak the way you came, and then use an app on your phone to navigate your way through the backroads. The extended walk takes around twenty minutes or so in total. (I had to ask three or four staff members at Karnak before I could get any information about this.)

The Mut temple area is open, but requires its own ticket. I just used my Luxor Pass, but if you don’t have the pass, try asking about the required ticket at Karnak’s main ticket kiosk.

As seen today, the Precinct of Mut is in bad shape and very little remains intact. But there’s still plenty of interesting features for old ruins enthusiasts to enjoy.

Mut was one of Amun’s consorts. She, along with Hathor, Sekhmet and Isis, was one of many personifications of the Egyptian concept of the Great Mother.

Though there’s not a whole lot of Mut imagery around, you will find a massive collection of seated Sekhmet statues. But why so many?

The statues were commissioned by Amenhotep III of the 18th Dynasty, who also built this temple. Sekhmet, the consort of Ptah, was simultaneously the goddess of healing and destruction.

While details are murky, some researchers suspect that there was a plague ravaging Egypt during Amunhotep III’s reign. And what better divinity to pray to than a fierce lioness who can also heal? (Eerily, these statues seem especially relevant at the time of writing.)

The heir to the throne, a prince named Thutmosis, died around this time. And his replacement was Amenhotep III’s other son, Amunhotep IV. Today, we know him as Akhenaten.

In addition to the ones here, numerous seated Sekhmet statues have made their way to museums all around the world. It’s estimated that Amenhotep III commissioned as many as 700 of them!

Elsewhere around the complex are some broken colossi, ruined temples from various later pharaohs, and some statues of Amenhotep III himself. Thankfully, the Precinct of Mut contains a lot of informational signage about what each particular area was used for.

The Precinct of Mut also has its own Sacred Lake, which appears surprisingly natural compared to the one at Karnak.

If you still have yet to visit Luxor Temple, now is the time to head over there. As mentioned above, Karnak Temple represents the creation of the physical universe. Luxor Temple, on the other hand, is dedicated to man and the universal principles embodied within him.

In other words, Karnak is the macrocosm while Luxor Temple is the microcosm. And the two temples were originally connected by a long sphinx-lined causeway. For the first time in modern history, excavators are working on clearing the entire 2 km path for tourists to enjoy. (Update: the pedestrian road is now open.)

Additional Info

Egypt can be a difficult country for independent travelers. The tourism industry has primarily relied on package group tours for decades. For some reason, it seems as if the government doesn’t really want tourists to take public transport. But it’s thankfully still possible.

The easiest way to get from Cairo (or Aswan) to Luxor is by public train. The train from Cairo to Luxor takes about 9 or 10 hours and there are both day trains and night trains. Strangely, the night train (which the government prefers tourists to take) can cost over $100!

Yet the day train only costs a couple hundred Egyptian pounds, or roughly $13 USD. But if you go to the train station and try to buy a ticket in person, they will NOT sell it to you. They will only offer you the expensive night train tickets.

Luckily, even though they don’t sell tickets to foreigners in person, it’s still perfectly legal for foreigners to ride the day trains. The trick is to just buy them online from the official Egyptian National Railways site and print them out before departure.

It seems like you can’t reserve more than a couple of weeks in advance. Furthermore, you will need to create an account on the web site and agree to the terms before searching. If you’re not signed in, the search will turn up blank.

Here is an excellent resource for all train timetables in Egypt. It’s worth going for the nicest AC1 trains, which are still quite cheap. Snacks and coffee are sold onboard. But expect the entire cabin to reek of smoke, as people constantly use the space in between the train carriages as a smoking lounge.

If you’re not able to book online for some reason, here’s another solution: simply show up at the station, hop on the train and sit down. When the ticket inspector comes by, pay him. Strangely, while you can’t buy tickets from the ticket booth, this method is completely acceptable.

Learn more about Egypt travel in our Ultimate Ancient Egypt Itinerary.

During your visit to Luxor, it’s well worth getting the Luxor Pass if you plan on spending more than a few days there. There are two versions of the pass and both are valid for five consecutive days.

The PREMIUM version costs $200 and allows access to every site in Luxor, including the tombs of Nefertari (1400 EGP) and Seti I (1000 EGP).

The STANDARD pass costs $100 and includes everything in Luxor minus the tombs of Nefertari and Seti I. Together, those tombs cost around $150, so the PREMIUM pass is worth it if you’re interested in seeing them. (Learn more about prices HERE)

Adding up the individual ticket costs of all the attractions I visited in Luxor, I saved a significant amount of money with the pass. The best part, though, was the convenience. The ticket system for sites around the west bank is confusing, with the ticket booths often far apart from the sites themselves.

Without the pass, if you ride past something that looks interesting, you can’t just go in. You’ll have to find the ticket booth and then ride back again. The pass is perfect, then, for those who like to explore.

Furthermore, the pass allows for multiple visits to each attraction. You can visit the expensive tombs multiple times, while photographers can freely return to temples to get optimal lighting conditions.

Note that if you’re coming from Cairo and already have the Cairo Pass ($100 USD), you can get 50% off the Luxor Pass! The deal even works with the PREMIUM Luxor Pass, allowing you to get it for $100!

Considering all that I visited, with both passes I saved over $250 in Cairo and Luxor.

To get the Luxor Pass, you’ll need to bring your original passport, a copy of your passport, a passport photo (exact size isn’t so important) and USD in cash. And be sure to bring your Cairo Pass for the discount.

At the time of writing, the Luxor Pass can only be purchased at Karnak Temple and possibly near the Luxor Museum. (For whatever reason, many locals in the tourism industry don’t seem to know about this pass. Check the Egypt Tripadvisor forums for the most up-to-date information.)

I bought mine at Karnak and annoyingly, the guys at the desk are running a little scam. They claimed that I needed a photocopy of the Cairo Pass even though I had the original. They wanted an extra 200 EGP for them to make a simple photocopy. Just eager to get on with my day, I haggled it down to a 50 EGP ‘fine.’ At least I still got the 50% discount.

I don’t think a photocopy of the Cairo Pass is an actual requirement, and they were probably just making it up. From what I read online, they told other people completely different reasons for why they needed to pay more.

In Luxor, the east and west banks of the Nile River couldn’t be more different. The east is the bustling city center where most of the hotels and restaurants are located. This is where you’ll find the train station and the Luxor Museum. And of course, Karnak and Luxor Temples.

The west bank is much quieter and less developed. But overall, the west bank has more tourist attractions. Not only are all the tombs here, but there are plenty of mortuary temples to visit as well. While you can see everything on the east bank in a single day, you’ll need two or three full days to explore everything on the west bank.

That’s why I recommend staying on the west bank. And as the area gradually develops, there are a lot more hotels to choose from nowadays.

Overall, the west bank is pretty spread out. But if you stay close to the ferry port, you’ll get the best of both worlds. Not only will you get a head start on visiting the west bank attractions each morning, but getting to the east side and back will be easy as well.

To really make the most of your time in Luxor, I recommend staying on the west bank, getting the Luxor Pass (see above) and renting a bicycle. You can rent a bicycle for the day from numerous west bank shops at somewhere between 30 – 50 EGP.

I stayed at a place called Sunflower Guest House which was right by the ferry port. The rooms were spacious and clean and I had no issues with my stay. But after my arrival, I discovered that there are plenty of other accommodation options right nearby.

For those who still want to stay on the east bank, Bob Marley Guest House seems to be the most popular place for backpackers. And those with a much bigger budget tend to stay at the Winter Palace.

If the Winter Palace is out of your budget, nearby is the Iberotel Luxor, which offers a luxurious atmosphere at a more modest price.

Pin It!