Last Updated on: 22nd November 2019, 05:36 pm

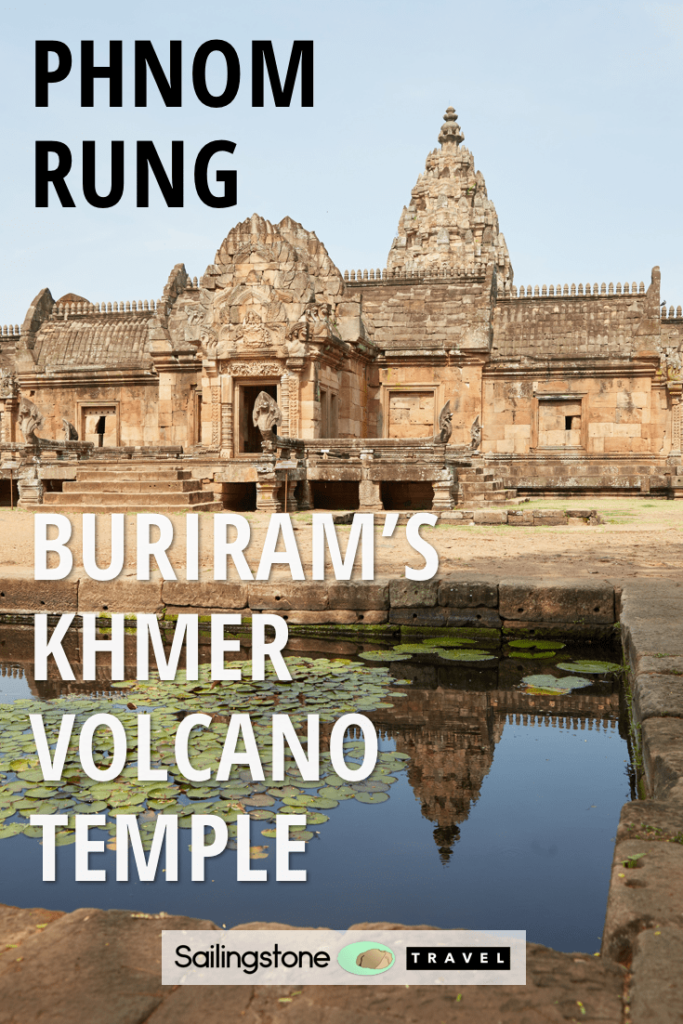

Mostly built in the 12th century, Phnom Rung was one of the Khmer Empire’s most important temples outside of Angkor. Later on during the reign of Jayavarman VII, it was even a prominent stop on the road he built connecting Phimai with the capital of Angkor Thom. But nowadays, the impressive temple gets much less attention than it deserves.

Built on top of an extinct volcano, Phnom Rung is situated in the small town of Nang Rong in Buriram Province. Though few tourists make it out there, Phnom Rung and neighboring Muang Tam remain remarkably well-preserved. This is largely thanks to extensive restoration which took place throughout the ’70 and ’80s. In fact, they could even be considered some of the most impressive temple ruins in all of Thailand. Whether you’ve visited Angkor and crave something more, or are limiting your trip to Thailand, Phnom Rung is worth the journey there.

Phnom Rung

Phnom Rung was built in the Angkor Wat style of architecture that was prevalent in the empire from around 1080 – 1180. Aside from Angkor Wat itself, other examples of the style include Chau Say Tevoda, Thommanon and Banteay Samre (all in Cambodia). While all of these temples, Phnom Rung included, have their own distinct temple layouts, what they all share in common are similar-looking prasat sanctuaries. (Learn about the basics of Khmer architecture here).

According to an inscription on Phnom Rung’s stele, the temple’s construction was overseen by Prince Narendraditya. Narendraditya was the nephew of Suryavarman II, the builder of Angkor Wat. Supposedly, he retired from the military and left Angkor to live on top of this mountain as a hermit. But considering all the staff required to maintain these elaborate Khmer temples, one wonders how much time he really would’ve had alone.

While many Khmer temples were made to resemble mountains, only a handful were actually built on mountaintops. And nearly all of these mountaintop temples were dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva, who according to legend, lives on Mt. Kailash, a real mountain in present-day Tibet. Phnom Rung, like its counterpart Preah Vihear, is meant to symbolize Shiva’s abode.

Another thing Phnom Rung shares in common with Preah Vihear is its long, straight walkway leading up to the temple itself. It stretches out to around 160 meters long, while the path is about 9 meters wide. The flat portion of the path is lined with stone carvings meant to represent the tips of lotus buds. And during the approach, the tall tower of the temple’s central prasat is visible the whole time.

Just before the steep staircase visitors walk up an elevated platform known as the ‘first naga bridge.’ The ends of the platform are flanked by multiple naga balustrades carved in the typical Khmer fashion. The Khmers, in fact, even believed themselves to be descendants of a naga serpent who married a local princess. This design also inspired the naga staircases seen all over Theravada Buddhist temples in Thailand today.

The steep climb up 52 steps brings visitors to the elaborate eastern entrance gate. Khmer temples dedicated to Shiva typically faced east, though exceptions were made when topography got in the way. Luckily for the builders of Phnom Rung, the layout of the mountain conveniently allows it to face east as well.

There are four square-shaped lotus ponds in front of the temple, while another raised naga platform leads right into the main entrance. Intricate carvings on the lintels and pediments above the doorways depict scenes from the Indian epic, the Ramayana, while Shiva himself makes an appearance as a wise old sage.

Despite its elaborate entrance, Phnom Rung’s inner layout is surprisingly simple. Inside the outer walled enclosure is a single central prasat with a gopura attached to its eastern door. Entering the inner sanctuary, the entrance to the gopura is the first things visitors see. And above the doorway is some of Phnom Rung’s finest artwork.

The pediment contains another carving of Shiva, this time in his multi-armed form. The base on which he stands is likely meant to represent his home of Mt. Kailash. Look closely in the lower right corner and you’ll notice the elephant god Ganesh, who, according to Hindu mythology, is one of Shiva’s sons.

Below Shiva, the lintel just above the doorway depicts the Hindu creation myth. Here we see Vishnu reclining on the serpent Ananta, who lays across the primordial waters of the cosmic ocean. A lotus flower sprouts from Vishnu’s naval, on top of which sits the four-faced Brahma who’s tasked with creating the world anew. This carving had actually been looted from the temple, ending up at the Art Institute of Chicago. Once it could be proven to come from Phnom Rung, the United States returned it to Thailand in 1988.

Outside the main sanctuary is a statue of a dvarapala, or temple guardian. This is actually a rare treat to see at an ancient Khmer temple, as nearly all the ancient sculptures are now kept indoors at museums. Originally, though, Khmer temples would’ve had stone statues everywhere, not unlike what you see nowadays at temples in Bali.

Inside the gopura is a statue of Nandin the bull, the animal vehicle of Shiva. Bull statues were a common site at Khmer temples dating back to the earliest ones in the 9th century. This particular statue sits facing the interior of the main prasat, which contains yet another important symbol of Shiva.

Surrounding the bull are small carvings of divinities of the four quarters, such as Varuna, the ocean god.

Rather than a statue depicting his likeness (though those did exit), Shiva was typically worshiped at temples in the form of a shiva linga. The linga is a phallic symbol representing masculine energy, and it was typically placed on a yoni, which symbolizes the feminine aspect of nature. Therefore, the two together could be likened to the yin yang symbol of Taoism. During rituals, priests would pour holy water over the linga, and the Khmers even installed special drainage pipes to let the water out.

Phnom Rung was deliberately built so that on the summer solstice, the sunrise can be seen rising directly over the linga from outside the temple. The linga there today is a recent replacement added so that modern people can enjoy this natural spectacle, which supposedly attracts quite the crowd each year.

Also within the central prasat are carvings depicting scenes from the Mahabharata epic, such as the archery contest held to win the beautiful Draupadi’s hand in marriage. Though Arjuna would win, Draupadi would end up marrying all five Pandava brothers at the same time!

Check out the back (western) end of the complex where you’ll find guardian lion (singha) statues instead of the nagas in the front. Surrounding the entire temple, meanwhile, was an enclosure that functioned not just as a wall but as a gallery. Unlike the outer gallery at Angkor Wat, though, this one contains no bas-relief carvings.

Though most of Phnom Rung’s structures, as mentioned, were built around the time of Angkor Wat, there’s actually one that’s much older. The small prasat off to the side is believed to be as old as the 10th century, which indicates that the Khmer Empire expanded out to this area quite early on in its history. The structure features a carving of Krishna holding up Mt. Govardhana.

Elsewhere in the complex are structures known as ‘libraries.’ Though they were common at nearly all Khmer temples, nobody is quite sure what they were used for. They may have held important texts and artwork, or maybe they were used for special rituals distinct from those performed in the central prasat.

Phnom Rung also contains a structure that’s almost entirely collapsed except for its two colonettes where the door would’ve been. Experts believe that these were made in the style of Koh Ker, a town which briefly became the Khmer Empire’s capital for a couple of decades in the early 10th century.

Phnom Rung rarely gets very crowded, giving visitors plenty of time to walk around and observe its intricate carvings.

Back at the bottom, don’t miss an additional structure referred to as the ‘Hall of the White Elephant.’ According to legend, it was used as an ancient king’s elephant stable, but nobody knows for sure. Another possibility is that it was added much later by Jayavarman VII. In that case, it could’ve functioned as a rest house or maybe even a hospital. This temple was, after all, in the middle of the road connected Angkor with Phimai (current Nakhon Ratchasima Province in Thailand).

Muang Tam

While Phnom Rung is the more famous of the two, Muang Tam, at the base of the mountain, is nearly as impressive. The temple may even be a century older than Phnom Rung, with experts grouping it together with the mid-11th century Baphuon style of architecture.

The temple follows a very different plan from that of its neighbor. Within the outer enclosure is yet another enclosure in the center. And within that is a group of five prasat sanctuaries, which we’ll cover more below.

But what really sets Muang Tam apart from just about any other temple in the Khmer Empire are its moats. They’re actually inside the walled enclosure rather than out of it, which is highly unusual. There are four L-shaped pools in total, all of which surround the central walled enclosure. And each pool is decorated with a naga balustrade around its perimeter.

Looking at older photographs of the temple, it’s evident that the pools remained empty for quite some time. It’s nice to see that they’ve been filled in, which is something you’ll rarely see at Khmer ruins in Cambodia. In addition to just looking nice, moats generally represented the cosmic ocean from the Hindu creation myth.

Inside the inner enclosure is a cluster of five prasats (though the front one is all but completely ruined). The layout here is highly unusual. Typically, when the Khmers built five prasats together, there would be a larger one at the center with four other towers surrounding it in a quincunx pattern. Later temples featured the surrounding prasats at the cardinal points. But here we have two in the back, two in the middle and then a single tower in the front and center.

Throughout the Khmer Empire’s history, of course, there were a number of temples which broke the mold. But perhaps architects even had more freedom out here in the kingdom’s frontier districts.

Also within the inner enclosure are the ruins of two ‘libraries,’ the mysterious structures mentioned above.

During your time at the temple, take some time to admire the carvings. In addition to those of gods riding a kala, you’ll also come across familiar scenes like Krishna splitting open the snake Kaliya. Some of the carvings appear to be newer replicas added during the recent restorations.

The five prasats also once had stones resembling lotus buds at their tops, which are now laid out around the area.

Just next to the temple is a large baray, or artificial reservoir which the Khmers built all throughout their empire. They’re thought to have been built for agriculture but they may have been used for transportation purposes as well, with a now-defunct canal system linking them together.

Furthermore, as Khmer rulers often built temples in the center of barays, these bodies of water may have served some type of religious function as well, though perhaps not in every case.

Local Nang Rong Temples

If you have some extra time in town, there are some local Buddhist temples that you may want to check out. I only had time to see Wat Khun Kong, which was established in the Ayutthaya period by King Naresuan the Great. It was built in the 16th century during one of Ayutthaya’s military campaigns against Cambodia. This, of course, was long after the fall of Angkor when the Cambodian capital was already in Phnom Penh.

One of the most famous Buddhist temples in the area is Wat Khao Angkhan, which I didn’t have time (or energy) to see. While both Phnom Rung and Muang Tam can be visited in the same day, you may want to add an extra day in town if you intend to explore the area fully.

Learn more about transport and accommodation down below.

Additional Info

If you plan on visiting Phnom Rung, you’ll most likely also want to visit the Isaan region’s other major Khmer temple, Phimai. Phnom Rung is located in the small town of Nang Rong, Buriram Province (not to be confused with the capital city of Buriram). Phimai, meanwhile, is located in the town of the same name which is an hour bus ride from Nakhon Ratchasima (capital of Nakhon Ratchasima Province and known locally as Khorat).

Nakhon Ratchasima is about 3.5 hours away from Bangkok, while Nang Rong is 4.5 hours away. Buriram Province is further east, closer to the border with Cambodia.

The ideal travel route will largely depend on where you’re headed after. If you’re beginning in Bangkok and then returning to Bangkok, visit in any order you like, as just about every town in Thailand has a direct bus to Bangkok.

In my case, I started in Bangkok but wanted to head onward to Chiang Mai. Therefore, I began by taking a bus from Mo Chit bus station directly to Nang Rong. When buying the ticket, be sure to specify that that’s where you want to get off, as the bus’s final destination will surely be a larger city like Buriram’s capital. (Note: you could also fly directly to Buriram City, or even take a train, and then gradually make your way westward by bus).

The best option is to stay at the P. California Hostel, one of the only English-speaking accommodations in town. Wicha, the hotel owner, will be able to pick you up from the bus station. And to see the temples, you have a couple of options.

You can rent a motorbike from the hotel and ride around to see them on your own. This should cost a few hundred baht. Or, you can have Wicha himself drive you to both Phnom Rung and Muang Tam. Note that the official price is 350 baht per person, but the minimum is 2 people. Therefore, if you’re a solo traveler you’ll have to pay 700 baht. That’s probably still much cheaper than negotiating with a random taxi driver on the street! He can also take you to Wat Khao Angkhan for an additional fee.

Though I stayed at P. California and would recommend it, another English-speaking option in town is Honey Inn.

There are direct buses between Nang Rong and Nakhon Ratchasima. Nakhon Ratchasima is the transport hub of the Isaan region and is in fact one of Thailand’s largest cities. If your main objective is to get to Phimai and then move on from there, you’ll want to base yourself relatively nearby the bus station. As it’s a pretty big city by Thai standards, basing yourself in the city center will make it difficult to access the bus station. But for those wishing to see the sites in town, more centralized accommodation would make sense.

Phimai is easy to get to. Just walk to the bus station, tell them ‘Phimai’ and board a bus which leaves nearly every hour. It’s just about an hour away and the temple and National Museum are walkable from the bus station. Buses come and go frequently, so you won’t have to wait long to find a bus back to the city.

From Nakhon Ratchasima you can get a direct bus to just about anywhere else in Thailand, but try getting a ticket at least a day in advance. The ride to Chiang Mai is a grueling 14 hours, but at least it didn’t involve a transfer!

Pin It!